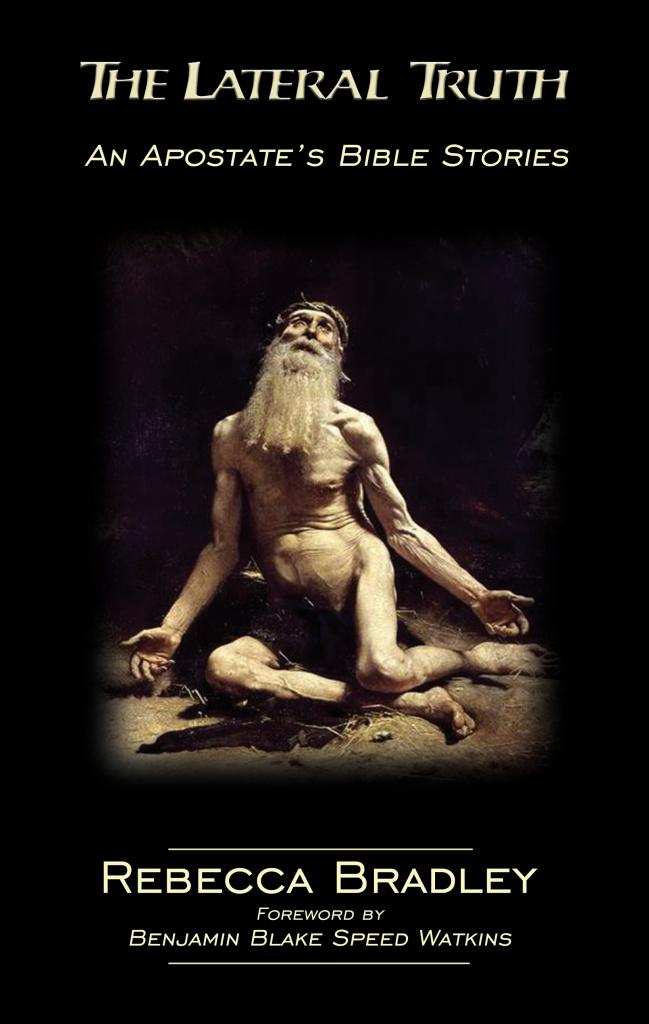

Rebecca Bradley, author and archaeologist with whom I used to blog, wrote a brilliant collection of satirical biblical stories titled The Lateral Truth: An Apostate’s Bible Stories [UK]. It was well received and has now been re-released in a new edition with a foreword by Benjamin Watkins, the host of the Real Atheology podcast. This edition is now available in paperback where it hasn’t been for a number of years.

Here is an excerpt from the foreword:

Satire of religion can be risky business. Speaking irreverently of religious authority and tradition breeds hostility because such ideology consists in some of the most dominant forces and institutions in history. Those who brave such heretical territory invariably place a target on themselves by religious extremists. The complexity of religion defies singular critique because it is permeated through a multifaceted and ever-changing world of ideas and their expression. Religion is like a virus with many manifestations, few treatment options, and the potential to affect multiple organs.

For much of human history, religion has clouded our reason, constrained progress, and corrupted the better angels of our nature. As adaptable and fluid phenomena, their nebulous appeals to non-universal revelations and undeserved authority structures have resisted, and often cruelly and unjustly punished, our questioning attitudes and dissent. When we finally achieve immunity from one dogma, it seems there are countless others waiting to infect hosts who are all too eager to believe little in the way of evidence but much in the way of faith. They are like hosts who welcome their parasites with open arms – victims who refuse to escape the clutches of their abusers – slaves who yearn for the bondage of their chains. This makes the need for a vaccine, intervention, or liberator all the more crucial to the human condition. Satire provides us with just such remedies, and Rebecca Bradley delivers on it.

To be sure, our religious traditions and forms of life are useful fictions or socially constructed myths that endure because of their effects rather than their substance, explanatory power, or moral virtues. Despite some of their more benign or even beneficial effects, religious traditions give rise to much more insidious features that are positively antithetical to human rationality and solidarity. Acts of apostasy, heresy, and blasphemy are met with hostility meant to discourage criticism both from out-groups, and also from within the in-group itself. Questioning attitudes and freedom of thought in a marketplace of ideas are stymied, and, as the painter Francisco Goya famously lamented, “the sleep of reason breeds monsters.”

The satire contained within The Lateral Truth shatters this sort of self-serving piety.

Rebecca Bradley gives us wonderful tools to better challenge religious orthodoxy and expose it for the absurdity that it is. Religious superstitions and dogmas may be false, but their effects on reason are very real in the sense that political rights, moral values, economic resources, and societal privileges have been built on their foundation. Bradley deconstructs familiar religious stories that often believe themselves to be beyond reproach. One must be bold to challenge the political and the social mores of people’s deepest spiritual convictions, and must be clever to wade through hostile piety to channel a rich history of religious skepticism. Bradley is aware that what she is saying to the religious in this book is what so many skeptics have already suspected but lacked the creative wit to articulate as such an exacting satire.

In 1759, the French enlightenment writer, Voltaire, published Candide, which roughly translates to all for the best or the optimist. This was also a satirical work that took aim at another enlightenment figure: the mathematician and theologian Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Leibniz is a major figure of seventeenth-century rationalism, having invented integral calculus independent of Isaac Newton. Leibniz’s theological work emphasized the concept of theodicy, which aims to provide a satisfactory response to the problem of evil. According to this problem, the God of the Western monotheisms that is so integral to the Christian tradition is ascribed the divine properties of being all-powerful and perfectly good. But the properties we ascribe to God have implications, and they constrain the way we would expect the world to be if it were created by such a being. If God has infinite power, then he can bring about any state of affairs, and because He is perfectly good, God would maximally desire to bring about the best of all possible worlds. But could this world, profuse with seemingly arbitrary evils, really be the best of all possible worlds?

Leibniz’s answer is a confident “Yes.” God created this world rather than some other world because any other world would have been worse than this one. This reasoning also provides us with an answer to another deep metaphysical question also posed by Leibniz: Why is there something rather than nothing? Why this something rather than something else? Leibniz seems content to insist that this reasoning dissolves the problem of evil and sits comfortably within human reason. There is no further problem here, and God’s power and goodness are left intact.

Voltaire wastes little time using his protagonist, Candide, to find the irony in Leibniz’s response. He sees this “best of all possible worlds” theodicy as little more than a shallow rationalization, and by the end of the story has pithily challenged the perfect being conception of God as either an incompetent idiot or a malevolent gardener in what is now considered one of the greatest satirizations ever produced.

Indeed, Voltaire, using Candide as his mouthpiece, asserts that the simple lesson in all of this is that we cannot be content with the hope that our struggles for truth, goodness, and beauty are all for the best, but rather we must cultivate our own garden; or as Kant would echo in his motto of the enlightenment: Sempre Aude – we must dare to know things for ourselves. While Candide is a permanent fixture in the canon of enlightenment reading, it was not always met with intellectual reverence, nor was Voltaire immediately praised for his witty charm and insights. The truth is rather much harsher. After all, Voltaire had staunchly aligned himself against the Roman Catholic Church and the French Catholic Monarchy by advocating for, among other things, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the separation of church and state. Fortunately, we enjoy much greater liberty to satirize religious traditions, authorities, and institutions today than did Voltaire in the Age of Enlightenment. The lesson of this history is the indispensability of satire when faced with stubborn absurdities. In the political sphere, our aims may be for liberty and equality of persons, but the marketplace of ideas is not the political sphere. Not all ideas are created equally, nor do they enjoy inalienable rights. People have dignity, and even the worst of us deserve at least some respect. The same is not true of ideas. Wars are waged because of failures of reason, discussion, and negotiation, so our first line of defense against these perils is the savage competitions between good ideas and bad ones.

Bradley joins the front ranks of religious skeptics and satirists like Voltaire with her call to rational conscience in the domain of religion. The Lateral Truth is a truly wonderful collection of satire that ultimately seeks to challenge the bad ideas of religion with charm and wit so that the good ideas of enlightened reason may prevail. It is a work that encourages us to think critically about the absurdity the religious faithful embrace, how it corrupts their minds in particular and a wider society at large, and how this absurdity has been allowed to persist for far too long.

Please support the work of Bradley and the skeptical publishing of Onus Books, and Loom and grab a copy!