I love taxonomy. I’m one of those guys who loves putting everything in its place. I love to buy storage solutions and put things away. Of course, when I run out of room… it gets pretty ugly.

Taxonomy is the science of identifying groups of like organisms and naming them. Every named organism has a unique scientific name and one or more common names. Locals and non-scientists tend to use common names, while scientists tend to use the scientific names. Why? Well, here’s a little quiz.

Which of these is a blackbird?*

Well, they all are. So if you say, “I saw a blackbird.” Which animal did you actually see? That’s why scientists use scientific names. These are unique to an animal and there can be no confusion. If you say, “I saw a Tursiops truncatus.” There is no question, among scientists, of what animal you saw.

I hope that everyone is familiar with the scientific naming system invented by Linnaeus in 1735. That was the start of the modern science of taxonomy. Here’s the categories of organisms from least specific to most specific (you see what I did there? nevermind…)

- Kingdom

- Phylum

- Class

- Order

- Family

- Genus

- Species

This can easily be remembered by the phrase “King Phillip came over for good sex.” ** The binomial nomenclature (literally; two-name naming system) is formed from the genus and species names.

Now modern taxonomists have determined that this isn’t enough boxes to put everything in correctly, so there are Domains (above Kingdoms) and “super” and “sub” and “infra” everything. There are superfamilies (between orders and families) and subphylums (between phylums and classes). It’s a right pain.

Over time, I’ve come to see the utter futility of it all. Sure, there are large groups that this makes sense for. But there’s a lot of things that seem, to the non-expert, to be a little weird. For example, hyenas are felids… not canines.

The Red Panda (time for a “squeeee” picture)

is most closely related to skunks, not pandas or even bears. It’s a weasel.

But things get even worse when you get into closely related species. Let me give you an example.

There’s this thing called a cline. At least that’s how I was taught it, that word seems not to be used much anymore. Anyway, let’s say you have a species of squirrel that lives in the southern end of the Appalachian mountain range, right up to the Gulf Coast. Just north of this species and sharing some of its range is another, closely related species of squirrel. So closely related, that interbreeding can and does occur, but only at the extreme north of the first species range and the extreme south of the second species range. I bet you can see where this is going…

Yep, just north and overlapping slightly with the second species is a third species. North of the third species and just slightly overlapping is a fourth. This continues all the way into southern Canada. It looks something like this.

A — B — C — D — E — F — G — H

Now, A can interbreed with B and B with C and C with D, etc. etc. etc. But in captivity, A totally ignores D, E, F, G, and H. In fact, the mating period and signals for A/B and G/H are so different, even if they recognized each other, they would never pair up. So, here’s the question…

Where do you draw the line?

What line? They are all different species right?

Well, yes, they are. But “species” is a touchy subject and blood at taxonomy conferences flows freely when people start trying to define species. Axes, chainsaws, machetes… it’s ugly.

So, let’s think about something that we know are the same species… we think.

Go ahead, tell me that those two dogs (Canis familaris) could successfully mate without human intervention. The mind boggles at just the physical dissimilarities. A step-ladder won’t even help that much. Not to mention carrying the pups to term. If the wolfhound was the mom, it would take the pups a week to get to a nipple.

But these are the same species… I think. This is another cline.

Miniature poodle to corgi to beagle to foxhound to pitbull to lab to German Shepard to wolfhound.

So where do we draw the line where the interbreeding stops? We can’t and that’s the problem. We can’t just say foxhound to pitbull, that’s where the line is. Everything smaller than these can mate and everything bigger than these can mate. Because that’s not true.

It’s a tough question and one that doesn’t have a good answer… in terms of taxonomy. But there is a solution to this conundrum and it lies with evolution.

Instead of trying to decide which animals look more alike (and why a weasel is called a panda). Let’s look at the evolutionary history of the organisms and just see who is most closely related to whom. This really took off with the knowledge of molecular biology and the ability to sequence DNA, starting in the mid 1980s, but really coming to the fore now.

Instead of the normal taxonomic system of closed little boxes within boxes within boxes. We get something that looks like this:

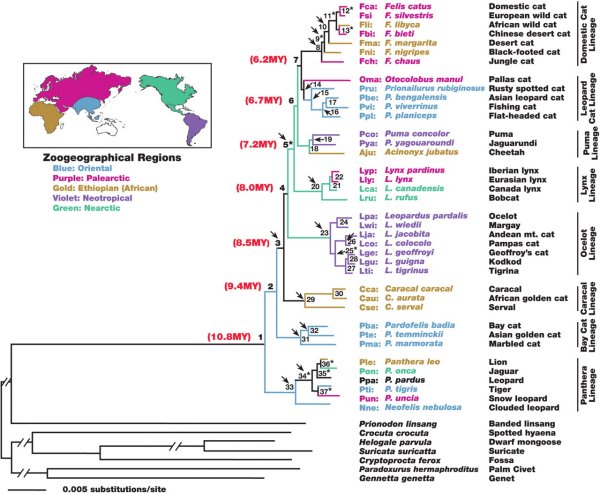

This is a fairly recent study of the entire felid group. From this chart, which is made from lots and lots of genetic analyses and some fairly significant computer time, we can see that most modern species of cats split off from each other about 10.8 million years ago. The Big cats broke off from the smaller cats at the time and have stayed a tight little group. Then you get into all the smaller cat species with the domestic cat breaking off from the European Wild Cat very recently (top of the chart).

Basically, the fewer branches between two species, the more closely related they are. Not all cladograms show time like this one does, but a few do.

Interestingly, the mere fact that we can make these kinds of charts pretty much undermines any form of Young Earth Creationism.

And yes, cladograms have been made that include every organism on Earth. The Tree of Life Project is an ongoing attempt to related everything. And yes, I’ve seen the big round one that supposes to contain everything, but it doesn’t. If you zoom in, you’ll see that humans are most closely related to rats. I was mad when I saw that. Do they think no one checks these things?

My original point, before I got distracted with pictures of red pandas, was that there are a lot of things in this world that are categorized that really probably shouldn’t be. Species, intelligence, political party, etc.

Wow, 1200 words to say that. Well, I hoped you learned something about taxonomy regardless.

_______________________

* The top is the Greater Antillean Grackle (Quisalus niger). Middle is the Common blackbird (Turdus merula). Bottom is the Carrion Crow (Corvus corone). Just in case anyone is curious.

** I find that much easier to remember than “King Phillip came over for good soup.” Perhaps I shouldn’t have taught it that way to 10th graders, but they bloody well remembered it.