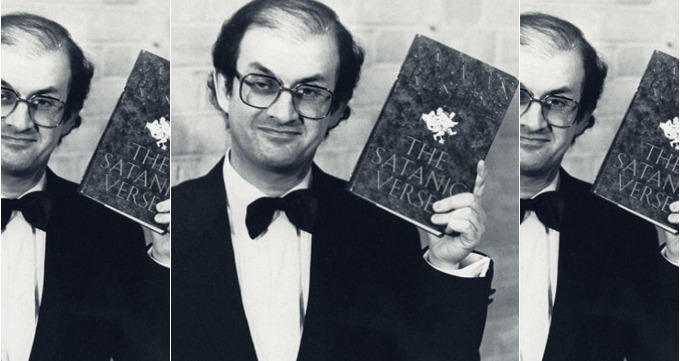

The February that just ended marked the 30th anniversary of the fatwa against Salman Rushdie. To recap: in 1988, the fictional book The Satanic Verses was published, a magical realism novel inspired by an apocryphal interpretation of a moment in the life of the Islam’s prophet, Muhammad. In February 1989 Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran issued a fatwa against the author to appease the masses, who were furious at the signing of the peace treaty that his regime had signed with Saddam Hussein. Khomeini would describe having to sign the treaty with Iraq as if he had been forced to swallow a poison pill, after promising his people that he would not sign anything because god was on Iran’s side.

Seeing the urgent need for an issue that would restore his image as a religious purist and appease the masses, Khomeini resorted to publicly offering money for the head of a foreign citizen who had legitimately exercised his freedom of expression in order to sedate public outrage at the signing of the treaty. The perfect smoke-screen. A fatwa is a religious edict that requires any Muslim to comply with it: in this case, killing Rushdie and anyone who was involved in the publication of his book; whoever carried it out or died in the process, would receive automatic access to heaven.

Why would the fatwa issued by a psychopath in a feudal pigsty affect the life of a recognized author in a civilized land like the United Kingdom? Because outrage also boiled in British Muslim communities, where thousands of offended Muslims protested expecting for Rushdie to appear, apologize, withdraw his book from circulation and never dare to write anything that would offend their sensibilities again. No, I’m joking: they expected the British government to hand him over so they could kill him and win heaven by avenging the “blasphemy”.

That’s right: thousands of apparently functional adults, living in one of the most advanced countries in the world, were completely unable to take responsibility for their own feelings and blamed Rushdie instead. To say that the British establishment’s response was really shameful would be an understatement: the media —businesses whose existence is due to the protection of freedom of expression— often invited intolerant preachers and it seemed quite normal to them that in the morning and noon news broadcasts there would be people calling for the murder of someone who had committed no crime.

The British government didn’t do much better. Between idleness and apathy, they ended up reluctantly and almost unwillingly giving Rushdie police protection, without even bothering to issue a defense of freedom of speech. The land of Locke, Hume, Bacon and Darwin was a silent accomplice when the head of one of its citizens was turned into a bounty by a foreign power. Margaret Thatcher fanboys who claim the Iron Lady was a standard-bearer of freedom may weep.

Even other writers sided with the Inquisitorial mob against Rushdie. Ten years after the The Satanic Verses was published and Khomeini issued his masses-appeasing fatwa, John Le Carré had a public spat with Rushdie going back and forth in a few op-eds —and in which Christopher Hitchens weighed in, on the side of reason and sanity—, for Le Carré thinks that “nobody has a right to insult a great religion”, as if that was even possible… which it isn’t, because it is not ideas but only living beings who are susceptible of being insulted; and because there is no such thing as a “great religion” — they are all recipes for misery, some more than others, but none is great, nor does any make anyone great.

On the 20th anniversary of The Satanic Verses, the incomparable Christopher Hitchens pointed out that the fatwa had been the opening shot in a culture war against freedom. Today, 10 years later, the state of the world seems to agree with him.

Although Rushdie has never been killed —not that they haven’t tried— the fatwa had several fatalities: the Japanese translator of Rushdie’s book, Hitoshi Igarashi, was stabbed in his office at the University of Tsukuba, where he taught literature; Ettore Capriolo, the Italian translator, was stabbed in his house in Italy; William Nygaard, the Norwegian publisher of the novel, was shot in the back and left for dead. However, as Hitchens never tired of pointing, despite these risks and constant death threats, back then the publishers, editors and bookstores refused to take the book out of circulation and never backed down.

Today, on the contrary, half of Charlie Hebdo is murdered (once again for the pseudo-offense of insulting a religion), and their colleagues panic just at the thought of reprinting their contents. Moreover, authors who are accused of offending the sensibilities of others today —and after being targeted by Twitter mobs— give in voluntarily, apologize and withdraw their oeuvre before it’s even been published (!).

In 2019, the Inquisition is more fashionable than ever. For instance, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Rushdie affair, The Independent‘s associate editor Sean O’Grady decided to read The Satanic Verses for the first time and publish a review of the novel — this is how he ends his review:

Rushdie’s silly, childish book should be banned under today’s anti-hate legislation. It’s no better than racist graffiti on a bus stop. I wouldn’t have it in my house, out of respect to Muslim people and contempt for Rushdie, and because it sounds quite boring. I’d be quite inclined to burn it, in fact.

Aside from the fact that this little creature deliberately confuses melanin with a set of ideas (?), the frightening thing is that the editor of a British newspaper has called for a book ban and has publicly fantasized about burning it, lest someone may find it offensive.

The excuse that pathological jealous male chauvinists used for years to reduce their wives to punching bags —the fascist idea that we have to take responsibility for the feelings of others— has prevailed. How many more lives will it cost us to banish it again as a justification for unacceptable behaviour? It’s been 30 years now, and things are not going in the right direction.

(pic: PA Photos/Landov)