It happens now and then a perfectly good scientist takes hold of a crank idea and plunges headlong into pseudoscience. Olaus Rudbeck discovered the lymphatic system and wrote hefty tomes arguing that Plato’s Atlantis was located in Uppsala, Sweden. Velikovsky was an accredited psychiatrist. Several Young Earth Creationists have genuine scientific degrees from respected institutions. Anatoly Fomenko, creator of the lunatic New Chronology, is an eminent mathematician at Moscow University. Etc.

It happens now and then a perfectly good scientist takes hold of a crank idea and plunges headlong into pseudoscience. Olaus Rudbeck discovered the lymphatic system and wrote hefty tomes arguing that Plato’s Atlantis was located in Uppsala, Sweden. Velikovsky was an accredited psychiatrist. Several Young Earth Creationists have genuine scientific degrees from respected institutions. Anatoly Fomenko, creator of the lunatic New Chronology, is an eminent mathematician at Moscow University. Etc.

Martin Sweatman, a chemical engineer at Edinburgh University, is earning a place on that list with his “decoding” of ancient art as a form of astronomical notation. In a couple of peer-reviewed papers co-authored with Dimitrios Tsikritsis and Alistair Coombs, plus a number of blog posts and now a book, Sweatman claims statistical validation of his claims so powerful that no other interpretation has any chance of being correct. Any of us who quibble, according to him, simply don’t understand science.

Now, I have quibbled quite a bit already: an initial critique of his Gobekli Tepe paper, a response to his rebuttal, a parody paper applying his analytical method to a different database (Looney Tunes characters) with similarly dazzling success, and some lively discussion in the comments of both our blogs. At the risk of seeming obsessive, I’m taking up Sweatman’s challenge to critique his second paper, which extends his grand hypothesis forward to Catal Huyuk and backward to Paleolithic art, as far back as 40,000 years ago. As his second paper builds on the results from the first, however, it is necessary to cover some old ground.

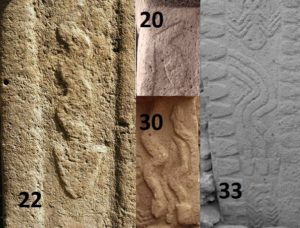

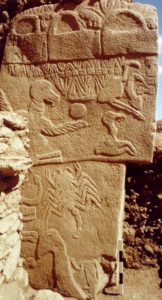

Recap: Pillar 43 at Gobekli Tepe is the cornerstone of the analysis. Sweatman interprets some of its engravings  as a constellation-map and some as solstice and equinox constellations, the two combining to form a “date-stamp” for 10,950 BC, the presumed date of the (highly controversial) Younger Dryas Impact. Applying a basic probability calculation, he concludes that his assumptions have been verified, and no other interpretation is possible.

as a constellation-map and some as solstice and equinox constellations, the two combining to form a “date-stamp” for 10,950 BC, the presumed date of the (highly controversial) Younger Dryas Impact. Applying a basic probability calculation, he concludes that his assumptions have been verified, and no other interpretation is possible.

What he actually demonstrates is how thoroughly a competent scientist can be seduced by wishful thinking. The paper is a dense pudding of circular reasoning, data taken out of context, and speculations that are subsequently treated as fact, all of which are clear markers of pseudoscience; errors and inconsistencies that Sweatman dismisses as irrelevant; and an overall amateurism with regard to the archaeology and iconography that is honestly beyond a joke. I’ve pointed some of these out in previous critiques, but there are points to add, and some that bear repeating.

Example: Snakes=Comets/Meteors

Sweatman’s reasoning:

- Snakes are the most prevalent motif at GT.

- There are no snakes in the faunal assemblage.

- The snake motif therefore means something different from the other animal images, which are represented in the faunal assemblage and allegedly signify asterisms. [Inference: the snake is not a specific asterism.]

- Snakes are dangerous, and assume threatening postures in the GT art. “Comets are certainly dangerous and destructive.”

- “The serpent motif is a good symbolic representation of a meteor track”.

On this basis, Sweatman concludes that snakes in GT art represent meteors/comet fragments, in particular the Taurid meteor stream presumed to be the source of the Younger Dryas Impact bolide (see below). But this is nonsense.

What the GT archaeologists actually say is that snake remains are largely absent, probably for taphonomic reasons, i.e., preservation factors. Snake bones are notably tiny and fragile. The bones from GT are badly fragmented to begin with, to the point where less than half of even the mammalian assemblage can be identified. To suggest that this means there were no snakes in GT and environs, and to assign cultural significance to it, is ludicrous.

Are comets “certainly dangerous and destructive?” Well, no. Most of them are just transient novel objects in the sky, which many cultures have taken as omens, for good or ill. Nor are meteors usually dangerous and destructive. A tiny proportion result in airbursts or impacts, but the rest are just impressive streaks across the night sky.

But even assuming a Younger Dryas Impact occurred (which is hotly debated), why would the people in the GT area have necessarily associated it with meteors? In fact, it is unlikely they would even have been aware of the alleged impact. A bolide coming down about six thousand miles away in the North American Arctic, as proposed by YDIH proponents, would not have been visible in Anatolia, would have minimal seismic effects there, and might leave a dusting of ejecta a few microns thick, some hours later. (You can play with the numbers here.) There is no evidence of widespread death and destruction at this date in the Middle East, and attempts to tie in YD bolide impacts with archaeological deposits in the Levant have been conclusively debunked.

To repeat, even if the YDI occurred, the people of Gobekli Tepe would be very unlikely to know about it, and would have no reason to associate it with the Taurid meteor stream, nor with a drop in mean temperatures over the following decades.

As for a snake being a good representation of a meteor track, I was unaware that meteor tracks wiggled.

Example: The Aurochs and the Fox

Sweatman’s treatment of the GT iconography is careless, inconsistent, and naïve. One frequent image, the fox, shows strikingly little variability in its diagnostic features across the whole site; and yet Sweatman manages to identify it as three different animals and three different asterisms: wolf/Lupus on Pillar 43, fox/Northern Aquarius on Pillars 2 and 21, and aurochs/Capricornus on Pillar 38. The latter image is damaged but perfectly recognizable as a fox.

The mistake on Pillar 38 has far-reaching ramifications. The sequences of images on Pillars 2 and 38, taken together, are the hook on which Sweatman hangs the remarkably flimsy chain of speculation which is the entire basis for his assertion that GT was particularly concerned with the Taurid meteor stream. A careful reading of the paper reveals that it is also the only basis for equating the fox with Northern Aquarius, the aurochs with Capricornus, the boar with Southern Aquarius, and Pillar 21 as a reference to the Taurids. Since the argument is based on a case of mistaken identity, all those identifications crumble.

It seems, indeed, he recently recognized his mistake with the “aurochs,” and withdrew the boar/southern Aquarius identification—Pillar 38 is not even mentioned in the second paper—but he has let the other claims stand. That is indefensible.

Example: The Ibex and the Lion

A particularly egregious error involves the middle “handbag” image along the top edge of Pillar 43. Sweatman is unsure what animal the image represents:

The middle ‘handbag’ is accompanied by a standing or charging quadruped of some type, perhaps a gazelle, goat or ibex, with large horns or ears bent backwards over its body. Alternatively, if it is pictured facing the other direction, it might depict a crouching rat, with a long tail over its back.

Now, it is obvious which end of the beast is which. It is also obvious the beast is the fierce feline (leopard or lion), which also appears on Pillars 27, 51, 56, and the two from the Lion Pillars Building. Diagnostic features, apart from the shape, are the tail held over the body, the suggestion of bared teeth, and the snarl-wrinkles on the snout. In fact, Sweatman even ranks “lion” as the #1 interpretation of this image. Mysteriously, however, he decides the beast’s arse is its head, and goes with the ibex/gazelle option.

You know, in archaeology we are not allowed to decide that a lion is an ibex, or a fox is an aurochs, just for the convenience of a pet hypothesis. But the wider importance of this error will become clear below, when we look at Sweatman’s treatment of Catal Huyuk.

Table 1 and the Statistical Test

Table 1 of the Gobekli Tepe paper is Sweatman’s summary of the constellations “identified” by his methods plus the additional zoomorphs from GT, which together form the input for his statistical probability calculation. One large red flag is that the fox and the lion both appear twice on the list: the fox as fox and wolf/dog/Lupus, and the lion as lion and ibex/rat/Gemini. Several other identifications are iffy; the crane as Pisces, for example, uses an image which is atypically bent, whereas most other crane images are straighter and not good matches for Pisces. Ophiuchus, which is in the wrong position anyway, is constructed by cavalierly combining the larger “bent bird” on Pillar 43 with an adjacent image to distinguish it from the “bent bird”/Pisces near the handbag, thus giving him two constellations for the price of one.

Sweatman, however, regards his mistakes as irrelevant. I pointed out that up to six of his eight identifications could be second-ranked (i.e., wrong) without affecting his conclusions. He proudly agreed, and claimed that was evidence of the strength of his statistical case; in fact, it’s a red flag that his methodology may be detached from reality. I pointed out that the “aurochs” on Pillar 38 was a fox. His reply: “It is rational…given our preceding statistical case, which provides the necessary confidence, to interpret it as an aurochs.” In other words, damn the facts, we’ve got stats. That is circular reasoning, and it’s also a pretty good summary of this paper’s approach.

But we can look at the probabilities in a much simpler way. Sweatman uses a pool of twelve images (his Table 1), and a target of eight images on Pillar 43. Treating this a basic lottery problem, how likely is it that any given combination of eight images would come up randomly? The answer is 1 in 495. But Sweatman’s pool counts two duplicates separately, the wolf/fox and the lion/ibex. Eliminating the duplications, we have a pool of ten images, a target of eight images, and a probability of 1 in 45. This is a far cry from Sweatman’s tortuously derived 1 in 43 million.

The Second Paper

Sweatman’s second paper, in collaboration with Alistair Coombs, carries over all the mistakes and wild speculations from the first paper, treats them as facts, and then piles on more. If the first paper was a house of cards, this paper adds a second storey. In a sense, since the first paper was demonstrably nonsense, anything that builds on it is necessarily nonsense as well—but I’m housebound with a cold, and have nothing better to do, so here goes.

Catal Huyuk

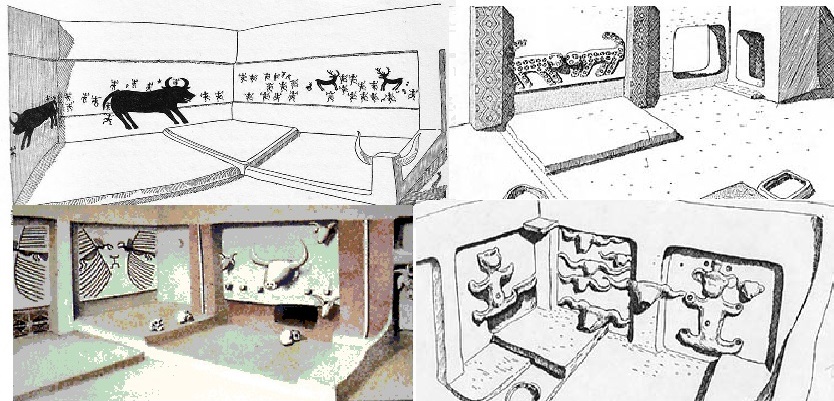

Like GT, Catal Huyuk is an amazing site with intriguing architecture, a nuanced faunal assemblage, and a rich iconographic corpus, some of which has compelling links with the earlier GT corpus. A town of structures so densely packed that they could only be entered from roof-level, it was excavated extensively in the 1960s and intensively in the last couple of decades, and we know a fair amount about it.

Sweatman’s analysis focuses on the so-called “shrines,” actually the decorated living rooms of some domestic structures, separated from the rooms devoted to food preparation and storage. They were also where the bodies were buried—literally, under the floor. Common decorations were wall paintings and installations incorporating horns, animal skulls and teeth, and high-relief plaster effigies of leopards, bucrania, and a “splayed” figure now interpreted as a stylized bear.

Sweatman assumes that the decoration of these “shrines” correlates with the equinox and solstice constellations during the time of CH’s occupation. From Stellarium, he identifies these as Virgo (summer), Capricornus (autumn), Aries (winter), and Cancer (spring). Claiming that the dominant (or only) decorative motifs in the shrines are aurochs/bull, bear, leopard, and ram, he proceeds to link these to certain asterisms. From Gobekli Tepe, he carries over Virgo (downward-crawling-quadruped, now identified with the stylized bear) and Capricornus (aurochs). The ram must therefore be Aries, just like today, which leaves the leopard to be Cancer. There are so many problems here that I hardly know where to begin.

First, he has no empirical basis for assuming CH’s interior décor is correlated with equinoxes and solstices.None. It does not follow from the claims in the Gobekli Tepe paper, nor does it fit the Catal Huyuk material. Aurochs/bull does dominate the installations heavily, but wild boar and stag are about as frequent as leopard, and other species are also present. More damningly, he fails to mention the content of the wall paintings: hunting scenes and scenes of vultures attacking headless humans, the latter being reminiscent of the vulture/headless man on Pillar 43 at GT.

Take the aurochs. In the first place, I have already pointed out that his equation of aurochs with Capricornus at GT is baseless. In the second place, a careful analysis of the distribution and treatment of aurochs bones at CH strongly suggests they were the focus of community feasting rather than everyday fare, which was dominated by domesticated sheep and goats. The installations involve wild animals, hunted rather than bred, with actual skulls and horns very likely serving as trophies or memorializations of actual hunts and subsequent communal feasts. In context, there is no reason to think they are references to constellations, and every reason to relate them to cultural practices strongly reflected in the faunal record. Sweatman’s explanation for the heavy dominance of aurochs in the installations—”possibly because of its earlier association with the Taurid meteor stream”—is not only a stretch, it is inconsistent with his claim that the fox was associated with the Taurid meteor stream at GT.

But it is the leopard that singlehandedly shoots down Sweatman’s synthesis. He explicitly links the CH version with the large feline images at GT, and assigns it to Cancer. This introduces a fatal contradiction. The “ibex” on Pillar 43 is identified as Gemini, a critical component of the date-stamp claim, but it is indisputably a big cat. If he were correct about the GT date-stamp, then the feline would have to be Gemini, and his interpretation of Catal Huyuk would fall apart. If he were correct about the constellations at CH, then the feline would have to be Cancer, and his date-stamp for Gobekli Tepe would fall apart. Either way, his synthesis falls apart.

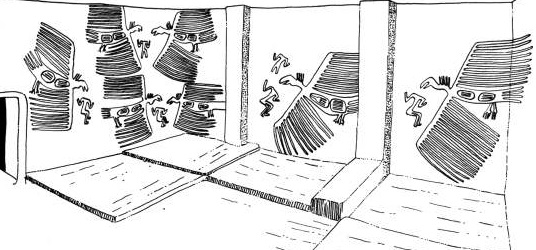

Paleolithic Cave Art

Catal Huyuk is only the appetizer—the Upper Paleolithic cave art of Europe is the main course. Sweatman claims that the animal/constellation matches derived from GT and CH can be traced back virtually unchanged to the Aurignacian period of the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, as far back as 40,000 years ago, along with a sophisticated knowledge of precession. And he claims to do this with a completely objective statistical test using the most reliable radiocarbon dates that archaeology can provide. Slam-dunk—or is it?

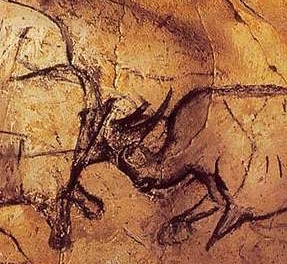

The Lascaux Date-Stamp

Sweatman begins by interpreting the famous shaft scene at Lascaux as a date-stamp for another bolide impact. The shaft scene involves a bison pierced with a spear, spilling its guts. Beside it is a supine man with a bird-like head, and next to him is a bird on a stick, the only bird image at Lascaux. To the left, a rhino ambles off in the other direction; on another wall is the head of a horse. True to form, Sweatman checks out the equinox/solstice constellations for the approximate date range of Lascaux, and decides that the bird must be Libra (spring) as per Pillar 43 at GT, and the bison must be equivalent to the aurochs, and therefore equals Capricornus (summer). By deduction, the rhino must therefore be Taurus (autumn) and the horse must be Leo (winter). Together, they form a date-stamp for 15,150 ± 200 BC.

But the interpretation is fatally flawed. To make the date-stamp work, Sweatman needs to assume that the figures form a unified scene. But the rhino and the man/bison scene are set slightly apart, and painted in different styles, using different techniques (spray and brush, respectively), and even chemically different pigments. The horse is a rather crude partial sketch on the opposite wall, with nothing to suggest it is related to the others—except the fact that Sweatman needs it to be: “The horse on the back wall is not often [never – RB] described as being part of this scene, but it is central to the interpretation described next.” He is begging the question again.

And suddenly, aurochs equals bison equals Capricornus. Sweatman even explicitly permits himself to make no distinction between aurochs and bison in his later statistical test; however, the Paleolithic peoples clearly did make the distinction, as both aurochs and bison images are present together in many of the caves he uses. Do both represent Capricornus, even when they occur in the same cave? Bear in mind also that aurochs=Capricornus is a junk identification based on an error, carried forward from the GT paper.

Then there’s the human and the bird. Sweatman compares the bird-headed man directly to the headless man on Pillar 43 at GT, and proposes that both reflect death and destruction from a meteor strike. I should have thought, though, that the headless man of Pillar 43, with vulture, has more in common with the headless men being ministered to by vultures in the spectacular wall paintings of Catal Huyuk, which Sweatman neglects to mention. The tiny bird on a stick, which he interprets as Libra, looks very like a spear-thrower, a class of artifact that is well represented in the archaeological record. In my book, headless guys with vultures are only superficially similar to a birdheaded guy with an atlatl and a wounded bison.

To further muddy the waters, he later announces that mammoths are also representative of Libra. One has to ask why the bird-topped stick in the Lascaux shaft is Libra, when mammoths continue to be appear on cave walls right through the Magdalenian? As far as I can see, the only answer is that he needs it to be Libra in this particular case, in order to derive his date-stamp.

Speaking of which, he then ties the date-stamp from this specious aggregation of elements to “a fairly strong climatic fluctuation at precisely this time recorded by a Greenland ice core” – but what he points to is a minor episode in a sawtoothed graph of climatic oscillations during the phase when the most recent glacial period was winding down. Is he going to propose a Taurid meteor strike for every wriggle in the graph? [To his credit, he admits in the second draft of the paper that the link with the climatic fluctuation is “unconvincing.”]

The Statistical Analysis

As with the GT paper, the centrepiece of this one is Sweatman’s statistical test. He assumes that the animals he identifies with certain asterisms should be chronologically correlated with their corresponding equinoxes and solstices, an assumption apparently carried over from his Catal Huyuk venture. He measures the separation between the radiocarbon dates for certain images, and the closest equinox/solstice corresponding to that animal in his Table 1. His null hypothesis is that the separations would be evenly spread across 3221.5 years, effectively a random distribution on either side of the centre of the equinox/solstice period; confirmation would require a roughly uniform distribution of separations up to 1074 years. He then flourishes his Figure 7, which duly shows roughly uniform distributions. Bingo.

There are problems.

To begin with, the animal/asterism matches are based on an invalid reading of the Lascaux Shaft scene, building on an unfounded interpretation of Catal Huyuk, building on a demonstrably flawed interpretation of Gobekli Tepe. But let’s ignore for the moment the fact that Sweatman’s “zodiac” is baseless, and just look at this test.

The first thing to notice is that the C14 dates themselves are not evenly spread across the entire range, but cluster into three groups with a few outliers. The group at about 15000 (all bison) has a maximum spread of 2240 years. The second group, mainly from Cosquer Cave, has a maximum spread of 2430 years. The third group, mainly from Chauvet, has a maximum spread of 1550 years. Sweatman is not testing a representative sample of Paleolithic parietal art, but a tiny database of figures from a limited number of sites, carefully selected for radiocarbon dating as part of a drive to systematize Upper Paleolithic chronology.

Now, the null hypothesis predicts a random distribution; but the null hypothesis is poorly chosen, because the sample itself is not randomly distributed, as explained above. The alternate hypothesis is a significant correlation with the nearest relevant equinox or solstice; but the alternate hypothesis is insufficient, because Sweatman does not eliminate other possible explanations for the distribution he finds. But there is another obvious explanation: the separations in Sweatman’s graph are limited by the time periods in which the selected caves were in use.

An example, to clarify: the Cosquer Cave dates. The post-glacial rise in sea level drowned the entrance to the cave and flooded the lower passage, but the surviving upper chambers offer a few dozen Gravettian handprints and finger tracings, and a treasure trove of Solutrean/Salpetrian-era parietal art. Recent Bayesian analysis combining the radiocarbon dates and other archaeological material dates the second phase to 21,700-19,250 cal BCE. All the animal images, whether directly dated or not, can be assumed to lie within that 2450-year range.

Sweatman’s paper includes five dated figures from this phase of Cosquer Cave, tied to three equinox dates, plus two stags/megaloceros added in a later blog post:

20950 = Lion/Cancer = Autumn. One figure, separation = 250

21200 = Bison/Capricornus = Spring. Two figures, separations = 1090, 1110

22700 = Stag/Aquarius = Spring. Two figures, separations = 1360, 1420

23250 = Horse/Leo = Autumn. Two figures, separations = 1270, 1450

On the face of it, only one of those (the lion) has a separation less than 1074 years, as per Sweatman’s hypothesis. But this is not the big problem. Also note that, with the later addition of Stag/Aquarius, he has two asterisms associated with two different but very close astronomical dates for the spring equinox. I’m past caring. No, the big problem for me is that there are nearly 200 figures in Cosquer Cave, representing eleven different species, all of which will have similar separations from the astronomical dates. This strongly indicates the separations are not due to any correlation between four particular species and the astronomical dates, but are an artefact of the time period during which the cave was in use. Similar observations can be made regarding the rest of the sample.

Sweatman’s test fails.

Throughout this exercise, Sweatman makes a point of how objective and scientific his approach is, since he uses only a carefully screened dataset of radiocarbon dates. Any archaeologist could tell him how dangerously naive that is. Radiocarbon dates do not come to us from on high, engraved on stone tablets; they need to be assessed in context. His input is based on indefensible animal/asterism identifications from GT, CH, and Lascaux. He treats non-random data, selected from a huge corpus to shed light on a particular set of archaeological questions, as if they were both random and representative. And on the basis of this tiny sample and an invalid statistical test of extraordinary clumsiness, he claims to have “decoded” the Upper Paleolithic.

As far as I can tell, however, Sweatman has little or no interest in the lifeways or rich artistic traditions of Neolithic and pre-Holocene peoples. His purpose throughout has been to use them as proxies for the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, for coherent catastrophism, and for the kind of alternative prehistory usually associated with the pseudoarchaeological fringe. He also displays the stereotypical dismissive scorn for archaeologists, combined with a profound ignorance of archaeology. In a recent blog post, he rather plaintively asks if archaeology is now a pseudoscience, since we did not welcome his grand synthesis with open arms.

Move over, Velikovsky. Move over, Fomenko. Martin Sweatman has entered the building.