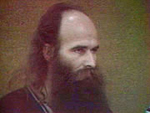

The ugly story of Roch Thériault and the Ant Hill Kids presents a malignant messianic cult in its smallest, purest form. Thériault, born in Quebec in 1947 and also known as Moses, God and Pappy, started his spiritual career as a lapsed Catholic, was kicked out of the Seventh Day Adventists, and made himself unpopular among Mormon polygamists—but he was the almighty lord of his own mini-religion.

The ugly story of Roch Thériault and the Ant Hill Kids presents a malignant messianic cult in its smallest, purest form. Thériault, born in Quebec in 1947 and also known as Moses, God and Pappy, started his spiritual career as a lapsed Catholic, was kicked out of the Seventh Day Adventists, and made himself unpopular among Mormon polygamists—but he was the almighty lord of his own mini-religion.

Oddly enough, his cult did not spring out of a specific religious-messianic agenda. Thériault got his start as a charismatic leader by organizing holistic detox seminars for the Adventists, aimed at helping smokers and other addicts to kick their habits. Drawn by his larger-than-life personality, a group of detoxifying acolytes left their jobs and homes to join him in that laudable work and other charitable initiatives; he dubbed them the Ant Hill Kids on account of their bustling ant-like industry. This group morphed into a commune, which became weird and cultish enough by 1978 that the Adventists kicked Thériault out, and severed all ties—including all financial support.

The seminars continued for a while, but attracted fewer customers. Meantime, the cult was evolving. Thériault, prophesying that the world would end in 1979, led his small but devoted band into the safety of the Quebec wilderness to ride out the period of God’s wrath – pretty standard chiliastic stuff. As usual, the world did not end, but this disconfirmation had no effect on Thériault’s power over his followers.

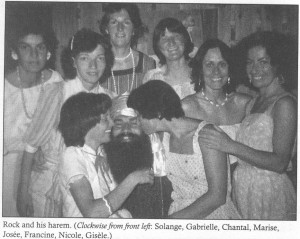

In fact, isolated in the rural Gaspé area of Quebec, and later in the Ontario wilderness, they became his willing prisoners, slaving to support him, bearing him children, watching him abuse those children sexually and physically, then losing those children to the child welfare authorities. At its peak, the cult numbered three men, nine women, and twenty-six children, mostly fathered by Thériault. All the women, even those married to his few male followers, became his concubines. All of them, men, women and children, suffered bizarre physical torture at his hands.

support him, bearing him children, watching him abuse those children sexually and physically, then losing those children to the child welfare authorities. At its peak, the cult numbered three men, nine women, and twenty-six children, mostly fathered by Thériault. All the women, even those married to his few male followers, became his concubines. All of them, men, women and children, suffered bizarre physical torture at his hands.

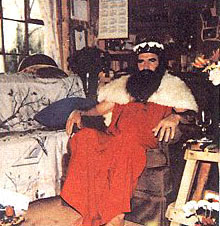

Thériault’s control was absolute. When he was in a good mood, there was no one more charming, more loving; but like the Jehovah he increasingly aspired to be, in his dark moods he was a terror. Anything could bring the terror on, a careless word, a crying baby, an undercooked chop, or a failure to respond to his sexual advances with sufficient enthusiasm.

But the worst times were when he started drinking, because then he would decide he was a surgeon. The chosen victim, fully conscious, would be held down by the others, and the healer—unscrubbed, with kitchen implements, or occasionally pliers or a blowtorch—would go to work. Sometimes he would delegate the surgery to others, and they would invariably comply. Somehow, while over the years various followers lost limbs, fingers, toes, teeth, testicles and so forth, in trade for a wide array of scars, the only fatalities until close to the end were a baby whom Thériault hamfistedly circumcised, and another who was deliberately left outside in subzero temperatures, and not surprisingly froze to death. Thériault and three of his followers actually did some jail time for the first child’s death, but the cult carried on, as did the abuse when he returned after his incarceration.

The beginning of the end was in 1988. Theriault decided his favourite (and legal) wife needed a liver operation to cure a stomach ache. As MacLean’s major 1993 coverage describes the event:

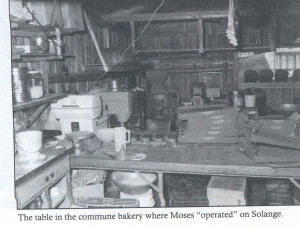

Within minutes, 32-year-old Solange Boilard, who complained of stomach problems, lay naked on a wooden table in one of the commune’s log cabins. Wearing red velour robes and a gold-colored crown–the symbols of his proclaimed role as “King of the Israelites”—Thériault punched Boilard in the stomach, jammed a plastic tube up her rectum and performed a crude enema with molasses and olive oil. Then, as she lay silent, he sliced open her abdomen with a freshly sharpened knife and ripped off a piece of her intestines with his bare hands. The “operation” completed, Thériault ordered another follower, Gabrielle Lavallee, to stitch up the gaping wound with a needle and thread. A day later, Boilard died in almost unimaginable agony–a hapless victim of what police in Ontario and Quebec describe as the most bizarre and violent cult in the history of Canadian crime.

Even so, it took a full year for the truth to come out, when the aforementioned Gabrielle finally left the cult and went to the authorities, minus an arm which Thériault had amputated with a meat cleaver. Thériault was eventually tried for Solange’s murder, among other crimes, and sentenced in 1990 to twenty-five years in prison—but he will not be released when that term is up, because a fellow inmate stabbed him to death in 2011.

Good riddance.

In this microcosmic messianic cult, all violence was turned inwards, and depended on the whims of the messiah and the compliance of his flock. Thériault was a monster, and his crimes were nauseating; however, he is not the most disturbing element in the story for me. I am more disturbed by the behaviour of his followers: on the one hand, cowed, beaten, maimed, tortured, terrorized; on the other hand, actively complicit in his atrocities, complicit in the abuse of their children, and hopelessly addicted to his charisma. Those who escaped almost always returned voluntarily to the fold, ready to both give and take further torture. After Thériault’s conviction, at least three of his concubines continued to be faithful to him for many years, even bearing him yet more children after conjugal visits.

He was a sadist, a psychopath, and gave new meaning to the term “mean drunk.” But his followers were clinically sane. And that, for me, is the most disturbing element of all.