Chapter 3: Dawkins’ Delusion, by William Lane Craig

This chapter by William Lane Craig looks to tackle Richard Dawkins’ main argument in The God Delusion, which can be found in the fourth chapter titled “Why There Almost Certainly Is No God.” Craig lays out the summation of Dawkins’ argument (in a very condensed version):

1. One of the greatest challenges to the human intellect has been to explain how the complex, improbable appearance of design in the universe arises.

2. The natural temptation is to attribute the appearance of design to actual design itself.

3. The temptation is a false one because the designer hypothesis immediately raises the larger problem of who designed the designer.

4. The most ingenious and powerful explanation is Darwinian evolution by natural selection.

5. We don’t have an equivalent explanation for physics.

6. We should not give up the hope of a better explanation arising in physics, something as powerful as Darwinism is for biology.

Therefore, God almost certainly does not exist. (19-20)

Craig responds by arguing that this “atheistic conclusion […] seems to come suddenly out of left field.” He mistakenly assumes these points of summation are some form of logical deduction or syllogism, when that was not Dawkins’ intention. Dawkins wrote just prior to this list that “at the risk of sounding repetitive, I shall summarize [my argument] as a series of six numbered points.” (emphasis mine) [1]

Craig further responds, arguing that even with a more “charitable interpretation” to view these “six statements, not as premises, but as summary statements of six steps in Dawkins’ cumulative argument […] even on this charitable construal, the conclusion ‘Therefore, God almost certainly does not exist’ simply doesn’t follow from these six steps, even if even if we concede that each of them is true and justified.” Craig continues to argue that this argument does not even take into account the cosmological argument or the ontological argument.

Craig did not appear to read Dawkins’ book very carefully. The very first paragraph in the chapter explained that Dawkins’ argument’s only purpose is to rebut the argument from design. He wrote,

In the traditional guise of the argument from design, it is easily today’s most popular argument offered in favour of the existence of God and it is seen, by an amazingly large number of theists, as completely and utterly convincing. [2]

Since he believed this argument to be the most popular and the most convincing Dawkins felt that this was the main argument that needed refuting. Craig also ignores the fact that Dawkins addressed these other arguments in Chapter 3 (Cosmological, Ontological, etc.).

Craig further argues that “in order to recognize an explanation as the best, one needn’t have an explanation of the explanation. This is an elementary point concerning inference to the best explanation as practiced in the philosophy of science. If archaeologists digging in the earth were to discover things looking like arrowheads and hatchet heads and pottery shards, they would be justified in inferring that these artifacts are not the chance result sedimentation and metamorphosis, but products of some unknown group of people, even though they had no explanation of who these people were or where they came from.” (21)

I would not agree that in the “philosophy of science” “one needn’t have an explanation of the explanation.” The reason is simple. Science is a means of explaining why things happen. If we cannot prove, let alone explain, our explanation then we have not come anywhere close to answering the initial question. This is why the explanation must have an explanation, or else it’s not science. Karl Popper writes:

Understanding a theory [in science] means, I suggest, understanding it as an attempt to solve a certain problem. This is an important proposition, and one which too few people understand. The problem that a theory is intended to solve may either be a practical problem (such as finding a cure for, or a preventative against, poliomyelitis or inflation) or a theoretical problem – that is, a problem of explanation (such as explaining how poliomyelitis is transmitted, or how inflation comes about). (emphasis mine in bold) [3]

Popper continues to use Newton’s theory as an example. Newton’s theory was an attempt to explain the laws of planetary motion proposed by Kepler and Galileo.

Craig’s final argument hinges upon Dawkins’ claim that god is complex. Craig argues that god “is a remarkable simple entity.” Of course, how Craig can possibly know this is yet to be seen. Furthermore, the very idea of trying to describe something that has never been observed in any way is absurd. We may as well discuss the reading habits of faeries, or what they like to eat. The exercise is pointless since we have no concrete data about that which we wish to describe.

Chapter 4: Richard Dawkins: Long on Rhetoric, Short on Reason, by Chuck Edwards

In this chapter Chuck Edwards has set his sights on Richard Dawkins’ The God Delusion. He begins his chapter by quoting Dawkins’ “humorous” quote about god that we looked at in a previous chapter. Of this quote, Edwards accuses Dawkins of taking a “below-the-belt swipe” at god and accuses him of “poisoning the well,” which he claims “produces a strong gut reaction: who would want anything to do with a God like that?” This is “appealing to emotions rather than to reason,” says Edwards. (24)

As I noted in Chapter 2, Dawkins’ intention was not to ‘poison the well’ against his target. It was meant more as “robust but humorous broadside than shrill polemic,” to quote Dawkins on his reasoning behind this passage. Regardless of his intentions, this description of the god in the bible is entirely accurate (just read Genesis 22:1-18; Exodus 13:2; Deuteronomy 7:1-2; Numbers 31:1-18, as just a few examples) and I would hope that these immoral acts carried out by god would force someone to pause and think about the being that they claim “loves” them and whom they worship every week at church. The fact that Dawkins brought this important issue out in the open in the beginning of his book demonstrates that he was thinking. Thinking about scraping the scales from the eyes of the believers by exposing them to the true nature of their god.

Edwards continues. He accuses Dawkins of erecting strawmen. He writes that Dawkins’ “opening statement” about god is a strawman because it is a “distortion of his opponent’s position” and that Christians and Jews “have never described God the way he imagines.” (25)

I still cannot believe how Christians have repeatedly jumped on this quote from Dawkins. It is such an irrelevant passage, so why so much attention paid to it? My initial reaction is befuddlement, but on closer examination brain scans have shown that when believers talk to god the scans depict the parts of the brain that light up when you are talking to another person. [1] These studies demonstrate that believers truly believe, I mean actually, truly believe they are talking to someone when they address god in conversation or prayer. Just as when someone becomes angered when their friend is insulted, so do believers when someone says something about their god. But I see no problem with saying the obvious. The description of god is right on target. It does not matter how Christians view god. What matters how god actually is when you read the bible. Regardless, Dawkins is not misreading the bible, Edwards is.

Next, he cites a single example of an alleged misreading of the bible by Dawkins. Edwards writes,

Dawkins recalls a story from Judges 19-21 of a man who allowed his concubine to be raped and murdered, then cut her to pieces and sent them to the twelve tribes of Israel as a rallying cry to battle. […] In the instance just mentioned, he fails to read the rest of the story, where he would have found that the last verse of Judges sums up the entire book with this editorial comment: “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did was he saw fit.” In context, this sentence summarized the message of the entire book: people left to their own devices often go wrong. (25)

If you read Judges, after this particular passage there many more horrendous examples of immorality. Does this single passage referred to by Edwards really mean to apply to each and every other act committed in Judges? No, and here is where Edwards might want to be more careful about who he chooses to cite, because David Marshall is no biblical scholar. To ascertain the true meaning of the passage it’s important to realize that the daughter is clearly proud to be sacrificed, and this is the entire point of the story. Indeed, in the New Testament Jephthah is heralded as a great person of faith (Hebrews 11:32-40). If this was truly wrong, as Edwards (and Marshall) argue, why is he held up as the perfect example of a person of faith? This makes no sense. But don’t take my word for it. Thom Stark (an actual biblical scholar) writes,

Here is a clear example testifying to Israelite belief in this period that Yahweh would give victory in battle in exchange for the satiation of human sacrifice. Why does Jephthah make this vow? Because the Ammonites were a formidable enemy, and Jephthah needed that extra divine boost in order to ensure a victory. Note that the text does not condemn Jephthah. Yahweh does not stop Jephthah from sacrificing his daughter. Moreover, according to the text, Yahweh is engaged in this whole affair, because after Jephthah made the vow, “Yahweh gave them [the Ammonites] in-to his hand.” Moreover, Jephthah is expressly one upon whom the spirit of Yahweh is said to have rested. In the New Testament, the book of Hebrews lists Jephthah as one of Israel’s great heroes of faith. […]

Certainly, Jephthah laments that it turned out to be his beloved daughter whom he had to sacrifice, but his daughter doesn’t! She sees that because Yahweh had given him victory, it is only right for him to keep up his end of the bargain. She takes the news of her impending inflammation rather well, all things considered. This shows that these assumptions were a normal part of life in that period. Human sacrifice to the deity was taken for granted; it was not a “rash” aberration. […]

Child sacrifice was considered noble in this world precisely because it was the greatest possible sacrifice that could be made. Children who were made subject to sacrifice weren’t despised by their parents; they were beloved. Sacrificing them was very hard, and that’s precisely the point! That’s what the ancient deities wanted – hard sacrifices. So when the story goes that Jephthah lamented having to sacrifice his daughter, that is the point of the text. Yahweh required a real sacrifice, and it hurt Jephthah, just as it was supposed to. But as Jephthah’s own daughter said, the bigger picture was the security of Israel, and she was happy to sacrifice herself for that cause. (emphasis in original) [2]

Moving on… Edwards’ next target is Dawkins’ arguments against god, and quotes Alvin Plantinga, who says Dawkins’ arguments are “sophomoric.” Next up is a quote from the “atheist philosopher” Michael Ruse who said that “Dawkins is out of his depth.” (26-27) Finally, he says that there are three different versions of the Cosmological argument, not just the one by Aquinas cited by Dawkins. Edwards says that the kalam cosmological argument “is considered by many current Christian theologians to be the strongest of the three.” He then lays out this argument, writing, “Whatever begins to exist has a cause…” and cites Christian philosophers’ reasons for the first premise.

Edwards continues his discussion of Dawkins’ arguments against the first cause argument in the next section titled “Sophomoric Smugness.” He accuses Dawkins of presenting a strawman when he fails to acknowledge that, according to theologians, god does not need a cause, and therefore, his counter-argument, asking “what caused god?” misses the entire point. (28) I would actually agree with this part of his argument, but at the same time, how can Edwards possibly prove this? Despite this accurate observation, Edwards says Dawkins “does not attempt to respond to any of the specific points that [William Lane] Craig and others bring up.” (28) I’m confused by this statement since Dawkins did cite a Christian philosopher: Thomas Aquinas, one of the most influential philosophers and theologians. Furthermore, this is not any form of counter-argument, stating that he didn’t argue against your preferred version of the argument. Edwards should have addressed Dawkins’ arguments against god. Mostly all he’s done is cite others who ridicule him and complain that Dawkins didn’t cite the argument he wanted him to, which is ridiculous.

Next, Edwards moves on from god to Dawkins’ discussion about the origin of life. He tries his hand at picking apart Dawkins’ argument utilizing the anthropic principle. (31-34) The anthropic principle essentially argues that given enough time and large enough numbers the improbable can become probable. In the case of the origin of life, Dawkins argues that the number of planets that could potentially sustain life are very large, thus providing fertile ground for this principle. Edwards disagrees and cites Guillermo Gonzalez’s and Jay Richards’ The Privileged Planet where they argue that the actual number of planets that could potentially harbor life is exceedingly much smaller, causing this argument from large numbers to fail. “Mathematically speaking, Gonzalez and Richards suggest the probability of a planet having all of the necessary conditions to sustain complex life is 10 to the negative fifteenth power, or one thousandths of a trillionth,” writes Edwards. (31)

Unfortunately, many of the calculations used by Gonzalez and Richards to arrive at this number are “erroneous.” [3] The criteria they used to calculate their results were entirely too restrictive and apply only to a very specific form of life. This is not to say that life cannot be found in environments dramatically different than the one that we inhabit. In fact, that’s precisely the case since we know of many kinds of organisms that can thrive in the harshest of environments, so placing such restrictions on their calculations is illogical.

Edwards tries a second line of argumentation. He gives Dawkins the benefit of the doubt and assumes his calculations about the number of habitable planets is correct. Even assuming the number of habitable planets is exceedingly large, Edwards quotes John Lennox who argues that “the anthropic principle” does not tell us “why those necessary conditions are fulfilled.” (32) Edwards accuses Dawkins of being “unable to give a scientific explanation for life’s origin.” (32)

Edward’s thinking is very muddled here. No, Dawkins does not try to explain how life arose since this subject is way out of his expertise. In The God Delusion he wrote:

The origin of life is a flourishing, if speculative, subject for research. The expertise required for it is chemistry and it is not mine. I watch from the sidelines with engaged curiosity, and I shall not be surprised if, within the next few years, chemists report that they have successfully midwifed a new origin of life in the laboratory. [4]

Dawkins clearly admits his lack of expertise in explaining the specifics of the origin of life so he kept to something he was better suited. This does not mean, however, that there are no answers to that how question. Over the decades there have been many experiments done that conclusively demonstrate that it is not that difficult to create building blocks of life.

Edwards next cites Johnathan Wells’ Icons of Evolution and argues that Dawkins is ignoring the “law of biogenesis” which “states that life only comes from pre-existing life. In other words, You don’t get something living from something non-living.” (33) Even more absurdly, in the last section dealing with this topic, Edwards writes,

The problem that Dawkins faces is there is no natural process known to man that can produce something living from something non-living. Atheists are fond of accusing Christians of “God of the Gaps” argumentation, where God is simply inserted to fill in our lack of knowledge. But it is clear that the issue here is not our lack of knowledge; to the contrary, it is what we do know from chemistry and biology that leads us to the conclusion that getting something living from something non-living is impossible. (34)

First of all, biogenesis is a theory proposed by those who used to believe in spontaneous generation, which is not what evolutionists say happened. Second, while “life” (if you follow the “minimalist definition,” which only requires “a self-sufficient system maintained by replication and subject to change by mutation.” [5]) has not quite yet been developed, scientists are half way there by successfully creating self-replicating RNA in the lab. [6] However, these gaps in our current knowledge do not and should not be filled with “god” or any other magical being. There is no need for it. History is filled with events and processes that were at one time unexplainable. It is illogical to continue with this line of reasoning when it has continuously failed for theists.

The final subject discussed by Edwards is the infamous “child abuse” issue regarding children and religion in The God Delusion. If I could choose one subject in TGD that caused more misunderstandings and more misquotes it would have to be this one.

Edwards writes,

[Dawkins] maintains that teaching religion to children is child abuse. This is not just an arresting figure of speech or an exaggeration to make a point; Dawkins soberly compares religious upbringing to sexual abuse, and finds religion the worse of the two. (35)

Edwards continues to trot out this strawman and cites studies which show how a religious upbringing often leads to positive developments in children. (36-37)

This quote has been taken out of context. This was an “off the cuff remark” that Dawkins blurted out during a lecture and he simply used this personal story as a segue to his actual point, which was the psychological harm of scaring young children with threats of hell and punishment. He did not claim that raising children in a religious environment in and of itself can be equated with the harm of sexual abuse. Dawkins writes, in context,

Once, in the question time after a lecture in Dublin, I was asked what I thought about the widely publicized cases of sexual abuse by Catholic priests in Ireland. I replied that, horrible as sexual abuse no doubt was, the damage was arguably less than the long-term psychological damage inflicted by bringing the child up Catholic in the first place. It was an off-the-cuff remark made in the heat of the moment, and I was surprised that it earned a round of enthusiastic applause from that Irish audience. […] But I was reminded of the incident later when I received a letter from an American woman in her forties who had been brought up Roman Catholic. At the age of seven, she told me, two unpleasant things had happened to her. She was sexually abused by her parish priest in his car. And, around the same time, a little schoolfriend of hers, who had tragically died, went to hell because she was a Protestant. Or so my correspondent had been led to believe by the then official doctrine of her parents’ church. Her view as a mature adult was that, of these two examples of Roman Catholic child abuse, the one physical and the other mental, the second was by far the worst. (emphasis mine) [7]

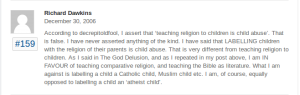

It should be obvious that Dawkins was not making the argument Edwards believes. Christians for years, despite direct statements by Richard Dawkins himself as to what he meant in that chapter, have been continuously misrepresenting and twisting his words. [8] This context ought to make it clear. I just wonder how much longer until Christians finally get it through their thick skulls how horribly they have been taking Dawkins out of context and putting words in his mouth. And Edwards accuses Dawkins of being “prejudiced” and “anti-scientific” based upon his distorted viewpoint. (37)

It should be obvious that Dawkins was not making the argument Edwards believes. Christians for years, despite direct statements by Richard Dawkins himself as to what he meant in that chapter, have been continuously misrepresenting and twisting his words. [8] This context ought to make it clear. I just wonder how much longer until Christians finally get it through their thick skulls how horribly they have been taking Dawkins out of context and putting words in his mouth. And Edwards accuses Dawkins of being “prejudiced” and “anti-scientific” based upon his distorted viewpoint. (37)

This chapter by Chuck Edwards was riddled with errors and an assortment of other fallacies. He clearly did not conduct any original research for this chapter and simply repeated wrongheaded clichés from within the Christian community.

Chapter 3: Dawkins’ Delusion, by William Lane Craig

1. The God Delusion, by Richard Dawkins, Houghton Mifflin, 2006; 157

2. Ibid.; 113

3. The Myth of the Framework: In Defense of Science and Rationality, by Karl R. Popper, Routledge, 1994; 157

Chapter 4: Richard Dawkins: Long on Rhetoric, Short on Reason, by Chuck Edwards

1. The Blaze: “This Is How Your Brain Reacts During Intense Prayer,” by Billy Hallowell (Oct. 22, 2012) – accessed 5-16-14

2. Is God a Moral Compromiser? A Critical Review of Paul Copan’s “Is God a Moral Monster?, by Thom Stark, Self-Published, 2011; 63-64

3. Panda’s Thumb: “The Privileged Planet Part 3: The Anthropic principle” – accessed 5-16-14

4. The God Delusion, by Richard Dawkins, Houghton Mifflin, 2006; 137

5. Life’s Origin: The Beginnings of Biological Evolution, edited by J. William Schopf, University of California Press, 2002; 113

6. The Daily Galaxy: “”Was It the Origin of Life”? Biologists Create Self-replicating RNA Molecule – accessed 5-16-14

7. The God Delusion; 317

8. Science Blogs: Dispatches from the Creation Wars, by Ed Brayton: “Dawkins and the Religion Petition,” December 29, 2006, Comment # 159 – accessed 5-16-14