Recently, I got into an argument on Twitter after reading this Tweet:

Contrary to the rhetoric schools feed kids these days, a 4 year degree ISNT mandatory to be successful.

— Credible Justin (@jlandmark) December 15, 2014

I responded that statistics show workers with bachelor’s degrees (have you noticed that only people who haven’t been to college refer to it as a “four-year degree”?) have much more earning potential than high school graduates over a lifetime. This was met (by a different tweeter) with a scoff that it’s college graduates compiling those statistics, so of course that’s what they say. I didn’t know how to respond to that, except to imagine a hypothetical paranoid person who wonders why plumbers are always the ones who find the most expensive clogs in the drain lines.

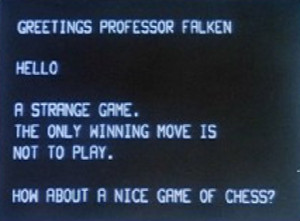

Several other tweeters chimed in and led the exchange down rabbit holes of anecdote (“I didn’t go to college, and I have a great job.”) and moved goalposts (“Income’s not the only yardstick of ‘success.'”). As with most debates on Twitter, probably my only winning move would have been not to play in the first place.

Of course there are exceptions, as there are to every rule, and many people don’t care about money, beyond having their basic needs met, but when income is the metric, it’s undeniable that college graduates do much better over their lifetimes than their peers who didn’t go beyond high school. This is true even when college debt is accounted for. It’s true even when the college grad’s later entry into the workforce is factored in. A college degree undeniably is an advantage in one’s career.

At least that’s the case today. It’s going to change in the near future. Sooner than anyone dares to realize, it’s not going to matter whether a worker has a college degree. Entire vocations will be eliminated in a matter of years, not decades, regardless of whether they require college training.

Rather, those jobs aren’t going to be eliminated. The work will still get done, just not by the humans who do it today. Robots will replace them.

Before continuing, I’ll stipulate that by “robots” I mean any sort of autonomously operating electronic construct, whether physical and kinetic, like a Roomba vacuum or a mechanical arm in a factory; or a stationary computer, or a software application, like the “bots” used in web crawling.

Cautionary tales about robots have been around for more than a century, beginning at least as early as 1920, when Czech author Karel Čapek wrote his play R.U.R., about a robot rebellion (the play is the source of the word “robot” in English).

Many, many malevolent robots with an agenda to “Kill All Humans!” (or enslave us, or replace us, or take vengeance upon us) have followed Čapek’s, such as the evil Maria doppelgänger in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis; the HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey; Roy Batty and his friends in Blade Runner; the rapist house in the novel and movie Demon Seed; Skynet; the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica; and Bender Bending Rodriguez.

Other robots have “destroyed” humanity simply by treating us too well. They anticipate and cater to every need and whim, causing their human masters to become indolent, ignorant, and unmotivated. The novelette With Folded Hands and the Pixar film WALL-E, with its resort spaceship’s infantilized residents, are two examples of this, but I know there are others out there. It’s an idea Ray Bradbury also explored in his stories.

Neither of those two main tropes is likely to happen, even if we do one day succeed in inventing true human-like artificial intelligences that can reason, go beyond their programming, and exercise as much free will as we do. Either way, it’s an existential anxiety. The fear of automation ruining our lives goes further back than the concept of robots. It’s part of the general ambivalence we feel toward our machines, even as we keep building them. John Henry, the “steel-driving man,” is the hero of his story, and he wins his race against the steam-powered hammer…but dies from the effort. And although we glorify Henry and demonize the greedy railroad baron pursuing efficiency at the cost of his gandy dancers’ livelihoods, no one would seriously argue it would be preferable to dig railroad tunnels by brute strength when technology is available to do it faster, better, and without risk to human lives.

No matter how many grocery store cashiers were idled by the invention of self-checkout scanners, none of us would put that technology back on the shelf. It’s made our lives more efficient and convenient, and we tell ourselves those erstwhile cashiers got better jobs, just as we believe John Henry’s colleagues set down their sledgehammers and went on to thrive in burgeoning Industrial Age factory work.

The real danger posed by robots is much more banal and much more immediate, and it’s different from the job loss John Henry and others like him faced. The robots will be taking millions of jobs, in all sectors of employment, and we are not ready for the paradigm shift this will cause.

I’ll be examining this brave new world in the following series of posts, which I’m calling The Robocalypse. Because I’m clever like that.