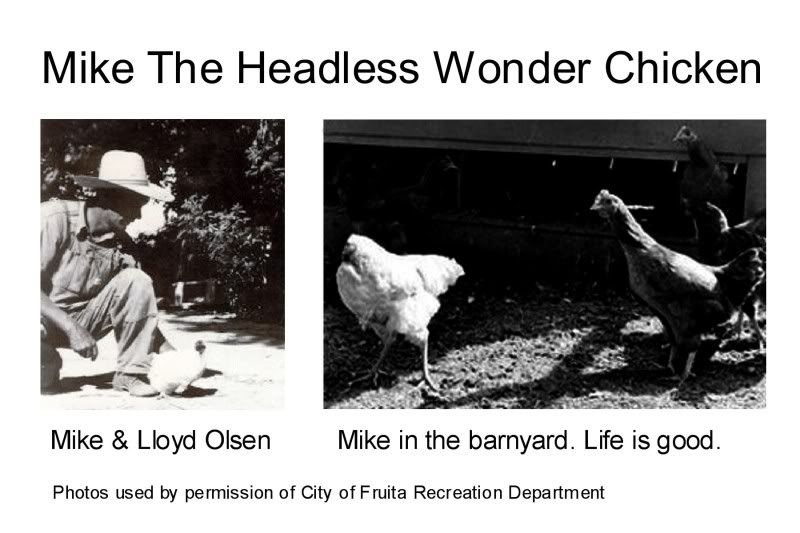

Have you ever heard of Mike, the Headless Chicken? Originally an ordinary Colorado chicken, he became famous in 1945 when his owner chopped off his head and he failed to die.

Enough of his brain stem escaped the axe for his essential chickenly functions to continue. He was given food and water through an eyedropper and soon became a star on the sideshow circuit, which was still popular at the time. He lived another eighteen months, and earned publicity like this:

It’s scientifically interesting, I suppose, to see how well Mike was able to thrive after his decapitation. He nearly tripled his weight in that last year and a half. Certainly, also, his anomalous condition gave him a life of comfort and ease far beyond what most chickens could hope for, and even more, obviously, than Mike himself originally had coming.

Still, this story bothers me. When I first heard about Mike, my reaction was “even a chicken deserves more dignity than that.” I know this makes no objective sense. Animals have no concept of dignity. Birds are probably not even self-aware. Mike’s life post-decapitation was no less fulfilling than that of any other chicken’s, and since he was never butchered and turned into fried food in a bucket, it could be argued that he got a pretty good deal, relatively speaking.

There’s a wide range of views on the rights of animals in the United States. From vegans to carnivores, PETA members to vivisectionists, almost all of us at least agree that animals shouldn’t suffer needlessly. That’s why cockfighting is illegal in all fifty states, dogfighting is illegal in all fifty states, and bullfighting is illegal in forty-nine states (Texas is okay with bullfighting).

Mike didn’t suffer, and he couldn’t have been embarrassed by the spectacle he became in the last part of his life. I have no rational reason for objecting to the way he was treated on the grounds that it was “undignified” (not least because it makes me a hypocrite; I once dressed up a cat in a reindeer costume, antlers and all).

What happened to Mike was an accident. Design student André Ford has an idea for an intentional version of the same idea:

By removing the cerebral cortex of the chicken, its sensory perceptions are removed. It can be produced in a denser condition while remaining alive, and oblivious.

The feet will also be removed so the body of the chicken can be packed together in a dense volume.

These chickens, if anyone ever goes with Ford’s idea, would never feel any pain. They’d never feel anything. Practically, this idea is no different from growing meat in a Petri dish, except that Ford’s chickens would still have hatched from eggs. So the process is marginally more “natural” (which is a virtue to many people).

Definitely, the “Chicken Matrix” (as Ford’s idea has been nicknamed) is a more humane approach to chicken farming than the current model, which is almost unspeakably cruel, and involves animals that unquestionably can think and feel and suffer. However, I still find it every bit as upsetting. Maybe it’s because of the kinship I feel with chickens. Chickens and humans are both animals, after all—both vertebrates, even. Treating a chicken like a grapevine or rose bush debases an organism that’s very similar to me, and I wouldn’t want to be treated that way myself.

Skeptics pride ourselves on our rationality, and on our ability to arrive at our ethics through reason and free thought, rather than received dogma. As one example, most of us (all of us?) favor marriage equality, and quite correctly assert to its opponents, most or all of whom are religious, that there is no rational basis to oppose it.

Religion isn’t the reason they oppose marriage equality. Religion is the excuse; the real reason is that they think gay relationships (especially gay and lesbian sex) are “icky.” Their objection is emotional, not dogmatic.

But that’s how all of us make our moral judgments. We base them on emotion, not reason. I didn’t realize that until I’d read this interview with Jonathan Haidt. When presented with a moral question, our reaction “this is wrong!” comes before we measure it against to our personal ethics, not after. This is an evolved trait, one we can’t help, as natural to us as our preference for sweet tastes and aversion to bitter.

It doesn’t mean there’s no objective right and wrong; just that humans aren’t great judges of right and wrong.

I’m going to be interrogating my beliefs much more carefully from now on.

What do all of you think about Mike, and the Chicken Matrix? Tell me in the comments.