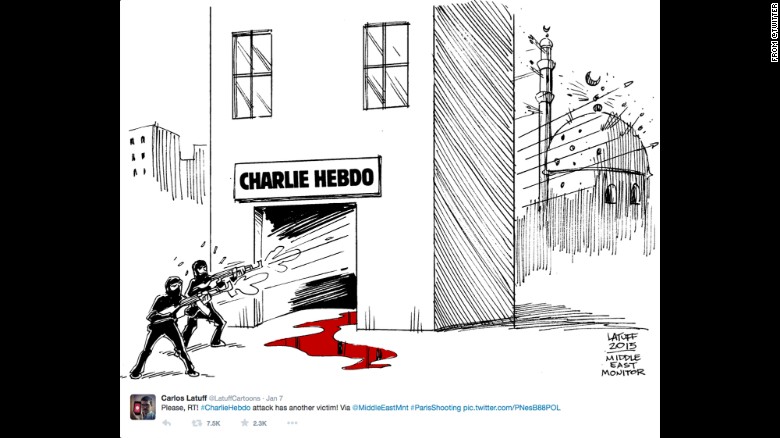

I am engaged in many conversations and debates across multiple platforms on the internet. At the moment, and in general recently, I have been wrapped up in many debates with my fellow liberals. The subject has been Islam and as to whether it is in some culpable proportion responsible for the violent extremism which is taking place across the globe. From the Middle East and ISIS (incorporating a number of different countries) to France and the Charlie Hedbo events; from Nigeria and Boko Haram to Kenya and Somalia with al Shabaab, things are not looking good. Before I get started, please make sure you read to the end of the article to avoid jumping to conclusions as some have.

The issue I have is one I hear all the time. Whether it be David Cameron, Barack Obama, Francois Hollande or other leaders and vocal people, the same mantra is repeated in various guises. Here is a selection of some of those quotes from recent months and days:

“This isn’t the real Islam”

“This has nothing to do with Islam.”

“Islam is a religion of peace…. They are not Muslim, they are monsters.”

And this is repeated by many of my liberal friends, including good people on this network. And I get it, I really do. I just disagree. So I was pleased when Ayaan Hirsi Ali stated:

“It is embedded in a world religion [Islam].”

The Hurriyet Daily News questions:

When it is the first time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam, one could look for a conspiracy behind it saying, “Is it really Muslims who have committed this?”

When it is the second time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam, there could be statements like, “The reason for this rage should be understood; that aspect should be focused upon.”

When it is the third time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam, there could be an interpretation like, “This is all the West’s fault; the West is reaping its own harvest; the West is responsible.”

When it is the fourth time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam, it could be said, “This has nothing to do with religion. Islam is a religion of peace; this is not the real Islam.”

When it is the fifth time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam, there could be a diagnosis like, “It is a reaction to exclusion, a reaction to the history of exploitation, a reaction to inequality.”

When it is the sixth time that one comes across a massacre committed on behalf of Islam… Well, there, you need to stop a little…

Because now it is time to look for the responsibility in ourselves. Now, the whole matter has reached the point where no excuses can be generated.

It is now the time to ask the question: “Why is terror coming from a religion of peace?”

Now, the time has arrived to develop a dignified, serious, firm objection.

The issue is this: liberals are claiming that these Islamic fundamentalists do not represent “true Islam”; that they have bastardised the true religion of peace. As Kenan Malik states:

Muslims are not the only religious group involved in perpetrating horrors. From Christian militias in the Central African Republic reportedly eating their foes to Buddhist monks organizing anti-Muslim pogroms in Myanmar, there is cruelty aplenty in the world. Nor are religious believers alone in committing grotesque acts. Yet, critics argue, there appears to be something particularly potent about Islam in fomenting violence, terror and persecution.

These are explosive issues and need addressing carefully. The trouble is, this debate remains trapped between bigotry and fear. For many, the actions of groups like the Islamic State or the Taliban merely provide ammunition to promote anti-Muslim hatred.

Many liberals, on the other hand, prefer to sidestep the issue by suggesting that the Taliban or the Islamic State do not represent “real Islam” — a claim made recently, in so many words, by both President Obama and David Cameron, the prime minister of Britain. Many argue, too, that the actions of such groups are driven by politics, not religion.

I do agree that the media, particularly the right wing media, are maligning Islam in a way which promotes bigotry and a sort of religionism which borders on racism. Yes, I get that, and I condemn inaccurate caricatures of Islam. But one should not silence the debate by pointing out inaccurate descriptions of Muslims and Islam and claiming that any critique falls into that category.

The question I have tried to investigate is whether Islam is at least largely causally responsible, as a religious wordlview, for the violence and terrorism which is presently taking place around the world. I did this first by showing the differences in approach of the two religions, epistemologically speaking, from the root of their holy books. Then I looked to show that arguers in this are often using the No True Scotsman fallacy. On a prima facie analysis, it would obviously be a yes. These terrorists are all Muslims and are all committing their atrocities in the name of Islam or in defence of Allah, or on account of Allah.

Things are never so easy. Defenders in the face of this criticism claim that such radicals commit their atrocities on account of socio-economic factors, human cravings for power, issues of politics and geography linked to the areas and whatnot. And these are certainly relevant causal factors in many of these situations.

First of all, before taking this on, it is wise to watch this debate on whether Islam is a religion of peace or not, between Zeba Khan and Maajid Nawaz, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Douglas Murray. It’s great and sets out a lot of the arguments:

The issue tends to be about who properly represents Islam, as I pointed out earlier with the quote, and whether the tough verses in the Qu’ran can be contextualised away, such as is often the case with the Old Testament and Judeo-Christianity.

In the above debate, and answering whether Islam is a religion of peace, Douglas Murray states that we can look at this in three ways:

- The example set and fact of Muhammad starting off the religion of Islam

- The holy book of the Qu’ran

- The actions of Muslims today

He actually puts 1) and 2) together, and then has a separate point for Sharia Law, which is something that most nonbelievers, if not all, would not want to abide by. I will not spend much time on that because it is wrapped up in a mixture of 2) and 3) for me. Is it, then, a case that any of these points allow for the defender to say that external factors are responsible for such violence, and that Islam as a religion is not to blame?

Muhammad

Muhammad was involved in 65 military campaigns, ruled by the sword and led by brutal example. Was Muhammad himself a man, a prophet, of peace? No. He was not. He was a leader who nicknamed his swords things like “Pluck Out ” and “Death” and who himself had a nickname from early Muslim historian Tabari of “The Obliterator”.

As historian Muir states:

Magnanimity or moderation are nowhere discernible as features in the conduct of Mahomet towards such of his enemies as failed to tender a timely allegiance. Over the bodies of the Coreish who fell at Badr, he exulted with savage satisfaction; and several prisoners,—accused of no crime but that of scepticism and political opposition,—were deliberately executed at his command. The Prince of Kheibar, after being subjected to inhuman torture for the purpose of discovering the treasures of his tribe, was, with his cousin, put to death on the pretext of having treacherously concealed them: and his wife was led away captive to the tent of the conqueror. Sentence of exile was enforced by Mahomet with rigorous severity on two whole Jewish tribes at Medîna; and of a third, likewise his neighbours, the women and children were sold into distant captivity, while the men, amounting to several hundreds, were butchered in cold blood before his eyes. … The perfidious attack at Nakhla, where the first blood in the internecine war with the Coreish was shed, although at first disavowed by Mahomet for its scandalous breach of the sacred usages of Arabia, was eventually justified by a pretended revelation. … The pretext on which the Bani Nadhîr were besieged and expatriated (namely, that Gabriel had revealed their design against the prophet’s life,) was feeble and unworthy of an honest cause. When Medîna was beleagured by the confederate army, Mahomet sought the services of Nueim, a traitor, and employed him to sow distrust among the enemy by false and treacherous reports; “for,” said he, “what else is War but a game at deception?” … And what is perhaps worst of all, the dastardly assassination of political and religious opponents, countenanced and frequently directed as they were in all their cruel and perfidious details by Mahomet himself, leaves a dark and indelible blot upon his character. [Note 1]

Now there will be differing opinions of Muhammad depending on what sources you refer to, of course, so we must be careful. However, his brutal militarism is not really up for debate. After the battle of Trench, for example, he decapitated 600-900 men and enslaved the women and children. He was harsh.

The immediate difference would be comparing this divine figure to Jesus who far from ordered deaths or spearheaded violent military campaigns. Christianity, with its bigotry and dodgy verses, can at least feasibly in some sense be called a religion of peace, with a love thy neighbour approach to politics. There is very little example set by its creator of war and warlike behaviour, or punishment and death (as far as the New Testament is concerned).

I suggest, for further information, people research the military conquests and person of Muhammad.

The Qu’ran

It appears that the Qu’ran, from a cynical point of view, is an ex post facto, post hoc rationalisation used to countenance Muhammad’s political violence. In secular history there is some argument as to whether he was purposefully deceiving or genuine in his beliefs of his revelation, over twenty years, which produced the Qu’ran as some direct revelation from God. I have read much of the Qu’ran and have been absolutely staggered by the violence and contempt for nonbelievers. It is dripping with contempt. Yes, there are some nice verses, like the Bible, but the ratio of nasty to nice is quite obviously heavily one-sided when you read it. Sura 2, al-Baqarah, is quite shocking to my sensibilities. By some calculations about 19% of the book is devoted to detailing violent conquest of nonbelievers.

There are too many verses to quote from, but here are a few:

Against them make ready your strength to the utmost of your power, including steeds of war, to strike terror into (the hearts of) the enemies of Allah and your enemies and others besides, whom ye may not know (8:60)

Strive hard (Jihad) against the Unbelievers and the Hypocrites, and be firm against them. Their abode is Hell,- an evil refuge indeed. (66:9, See also 9:73)

So often the fellow liberals with whom I have this discussion have not read the Qu’ran and I am staggered that they continue having this debate and defending liberal and moderate interpretations of Islam without themselves doing any of the requisite homework.

Critical scholar Ibn Warraq is one of those who has claimed that the passages in the Qu’ran which make more benign claims and diktats are abrogated by those more numerous ones advocating “violent action”. [Note 2]

The technique of naskh is iportant here. Burton, in his entry on Naskh in the Encyclopaedia of Islam (EI), states:

Many verses counsel patience in the face of the mockery of the unbelievers, while other verses incite to warfare against the unbelievers. The former are linked to the [chronologically anterior] Meccan phase of the mission when the Muslims were too few and weak to do other than endure insult; the latter are linked to Medina where the Prophet had acquired the numbers and the strength to hit back at his enemies. The discrepancy between the two sets of verses indicates that different situations call for different regulations.

Muhammad’s violent conquests increased as his power base grew, and with it grew the progressive revelation.

As David Hall says of Warraq’s work:

What the Koran says is not simply a matter of deciphering individual instances of words or verses, but of reconciling those instances once they have been deciphered. In the contemporary context this involves the fundamental question of the nature of Islam itself and vis-à-vis the Western world. We are forever being told by apologists for Islam that it is essentially a religion of peace and love, like all religions, and that anyone using violence in its name are not true or ‘real’ Muslims. That this apologia will not wash is made plain by Ibn Warraq in his discussion of the Muslim exegetical technique of naskh, or ‘abrogation’, whereby, according to the traditional chronology of events, early texts or revelations are over-ruled by later ones. By laying them out in detail Ibn Warraq shows that the majority of texts recommending clemency and tolerance are abrogated by later ones advocating violent action. It seems that ‘terrorists’ have as much right to consider themselves ‘good Muslims’ as any others. [Note 2]

What is clear is that the Qu’ran places believers so far above nonbelievers in a divinely declared hierarchy that you come away from the book feeling that you have been, as a non-Muslim, dehumanised.

And that, there, is a massive, massive problem for defenders of the religion of peace claim. Dehumanisation doesn’t have good press in the history of oppression and violence.

There are a number of places where Muslims are warned not to be friends with unbelievers and one that says you cannot be a true Muslim with such friends:

Thou wilt not find any people who believe in Allah and the Last Day, loving those who resist Allah and His Messenger, even though they were their fathers or their sons, or their brothers, or their kindred. (58:22)

So liberals and moderates who wish to shake hands and form a cohesive multi-faith world are defying their own holy book and divine commands in doing so.

Obviously there is not the space or time to do an exegetical analysis of the whole of the Qu’ran. I have looked at the differences between Islam and Christianity in “Islam vs Christianity: The core differences”. Suffice to say that the Qu’ran does not lend itself to being labelled a book of peace. As one commentator states of the immutable word which cannot be contextualised:

There is always the plight of context argument with Islam’s holy text Quran. The apologetic version is “Quran cannot be interpreted and understood except with its context.” This paraphrasing is constantly adduced by Islamic apologists whenever any argument against the violent verses within the text is raised.

But the way Islam justifies the divine origin of Quran automatically exclude it from the use of historical method of exegesis. There is this dilemma for Muslims to face. The text in fact is contextual as understood by Muslim explanation of its historical formation. But it is not a version of facts Muslims want to subscribe when they are fomented to believe in the interminable status of the text. Quran is meant for the whole of humanity is the undisputed Muslim belief. The belief proceeds on as the book is pertinent to the end of times.

Is not it implausible to believe in the infinite relevance of Quran and at the same time rise objections to critiques by embarking a context smoke screen? Should not Muslims give up the context excuse if they want to use Quran as a text which’s relevance is distended to the end of times?

There is only an affirmative answer to these questions.

…

Let us come back to the Quran. Allah spoke to a seventh century Arab in the latter’s language. And all what he said to this prophet is recorded to fructify a Quran. To sum it up, Allah sent his last message to this same prophet then stopped speaking downright. Because god sent his last message and promised to preserve it forever, he will not speak any more until the day of resurrection. He will not send any prophet, since sending a prophet will stir him up again. This is the end. God sent his final messenger, and even though he did not favor immortality to the messenger, he blessed the message with immortality.

So, Quran, Islam’s holy text is not a pushover. It is the ultimate message of god. There is nothing to add or subtract in it. All of its components are divine, equally divine. All are applied to all and all.

In conclusion, if there is a command in Quran, there is no need to look for its historical context since humanity from the formation of Quran to the end of times are living in the context of the text. It is the Muslim belief. God, Gabriel, Muhammad, three key figures formed Quran have infinite relevance, so the making (Quran) too necessarily possess the quality of being interminably relevant. If this is the common Muslim belief pertaining to Quran, there is no room for a context excuse in its case.

Thus, the context excuse in the case of Quran is flawed in its fundamentals. [my emphasis – source]

To play the context card, as Nawaz does in the above debate, is problematic, then, given the provenance of the Qu’ran as being the direct word of God (supposedly). To deny this immutable revelation, though, is to see the whole religion as a fraud of some sort. This is the vital key to the Qu’ranic problem, providing a huge barrier to proper reform, and probably why the religion has not gone through the sort of theological reformation that Christianity has. It is just so hard to claim you can explain away the nasty bits with historical contextualisation given the very nature of the book and how it was revealed. In fact, as Muhammad became more powerful, the conquests became more Qu’raniclly prevalent.

The Actions of Muslims today

It really looks like this third aspect offers the most hope. Who is a “real Muslim” and what is the current state of Islam today? Well, one problem that greets us, which is something that academic commentator Reza Aslan talks about often, is the prevalence of media outlets and people who declare “Muslim countries” do this or do that when there is a disparity between the actions of Muslim countries, that this is no clear commonality between, say, Saudi Arabia and Turkey or Indonesia.

And so the argument does really come, certainly in this section, to be about this true representation. Unfortunately for the liberal defender (I don’t like using this term because I see myself ordinarily as such – it should be a defender of this point who is invariably liberal) is that their argument can be turned on themselves. That radicalists are not true Muslims can be applied to liberals and moderates – they are not true Muslims and the radicals have it right.

Which is sort of my point. Looking at both 1) and 2) it seems that radicalists do have a more fundamentally accurate picture of what their faith is supposed to be. Now, we could adopt some sort of postmodernism which states that they are all right in some sense, and there may even be some merit in this. Obviously, from an atheist’s point of view, they are all wrong, but there must be some sort of accurate representation of what Muhammad set out, even if he was deluded and God wasn’t really revealing himself.

Looking at his life and actions, and looking at the holy book, I posit that fundamentalist Muslims are more fundamentally correct in their faith (the clue is on the word, right!). What Islam is supposed to be, I wager, from a Muhammadan point of view, is closer to the Jihadi version of struggle against the unbelievers. Liberal and moderate Muslims are more obviously contravening the important diktats of the Qu’ran, and do not appear to be following in the footsteps of Muhammad. Sharia Law does seem to be a natural add-on from the Scriptures, and most Muslims around the world appear to be in some sort of agreement with that.

Furthermore, the defender of the religion of peace mantra often claims that other factors, external factors, are responsible for the violence we see.

Politics is an external factor which supposedly influences these terrorists over and above the causal pull of Islam, and yet Islam is itself a religio-political movement dictating politics, laws and societal frameworks. This is indeed part of the problem. However, to deny Islam causal responsibility in these attacks around the world is very blatant special pleading. It is to say that other causal factors CAN be claimed to be at play (politics/socio-economics) but somehow religion can’t. I can’t over-emphasise this point enough. It is to say that other factors somehow necessarily supervene on religion as a causal factor without showing how this is so, but merely asserting it. Such defenders are happy to invoke causality, just not Islam. It is a causal cherry pick.

Islam does seem to be more than just a religion, and appears to work as a religio-political framework, with moral and legal diktats. Deferring, then, to political causality as opposed to religious causality is therefore problematic because they are essentially one and the same thing, at least to a large degree.

The personal views of Muslims around the world is a tricky business, but many surveys have tried to get a good view of the scenario:

Most Muslims are, like most other people, essentially decent, kind, and appalled at terrorist violence. Yet within Islam is another powerful sentiment, often coexisting with the kindness.

A Pew Research study shows that most Egyptian Muslims, a whopping 88 percent, think that death is the appropriate penalty for leaving Islam. In Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Pakistan and the Palestinian territories, solid majorities of Muslims believe in death for apostates.

In Turkey, a much more secular, much less conservative country, a solid majority opposes the death penalty for apostates, but even there, 17 percent of Muslims favor it. In Islam, leaving the faith isn’t simple apostasy, as westerners see it, but a form of treason against the larger community, called ridda. As many Americans consider death an appropriate penalty for treason, so do many Muslims, who do not draw the bright line between religion and the rest of life that many Westerners do, see it as the appropriate penalty for apostasy.

This is not a fringe view. It is mainstream. But even if Muslims favor inflicting death on fellow Muslims for apostasy, that doesn’t mean they favor violence against non-Muslims, and a majority don’t. But again the numbers are disturbing.

In 17 of 23 countries with large Muslim populations, most Muslims believe that sharia is the revealed word of God. Many of the others believe that sharia was developed by men from God’s word.

Of those who believe that Sharia is the word of God, most favor making it the law of the land. That number is as high as 99 percent in Afghanistan, 84 percent in Pakistan, and 77 percent in Thailand. Of those who believe it should be the law of the land, 74 percent in Egypt say it should apply to non-Muslims, with more than 40 percent of Muslims believing that across the Middle East.

The analysis of these numbers is tricky, but they underline an important point: The beliefs and attitudes that promote violence against non-Muslims for offenses against Islam are held by a minority of Muslims, but it is not a small minority. In terms of the absolute numbers, it is probably in the high tens or low hundreds of millions. [Source]

The statistics should not be taken in isolation, especially when more general moral positions are being exposed. Comparisons to non-Muslims should also be drawn to at least try and tease out causality. Because even in secular Islamic states like Turkey, the proportion of extreme views are far higher than with nonbelievers or other religions. Islam must play a role. Sharia, after all, makes absolutely no sense without Islam and the Qu’ran! One without the other is absurd.

Guy Benson has produced a pretty spot on article about this which included:

But does “extreme” lose its meaning when nearly half of a given population holds the position being described? I’m honestly not quite sure what to make of all of this data, and I’m reluctant to land on any sort of definitive conclusion pertaining to my internal struggle on these subjects. Again, I don’t want to fall into the trap of unfairly painting with too broad a brush, nor am I interested in doing the opposite by blithely ignoring data like this (or worse, attacking those who mention it as bigots). Which brings me to question number two: How can anyone fairly examine any of this data then loudly declare that Islamisms’ worst excesses have nothing to do with Islam itself? It’s one thing to argue over whether the “tiny fraction” narrative is accurate, or whether it does more harm than good. It’s a dangerous brand of delusion, however, to pretend that Islamist extremism (there’s that word again!) is entirely divorced from Islam. The many millions of people represented in the statistics above obviously identify as practicing, faithful Muslims. Shouldn’t that be enough for us, especially based on the Left’s own standards? Ben Shapiro made this provocative comparison on Twitter earlier in the week:

Leftists: You’re biologically male, but if you say you’re a gal, ok. Leftists: We’ll judge if you’re a real Muslim, no matter what you say.

— Ben Shapiro (@benshapiro) January 8, 2015

If we’re willing to subordinate biology to people’s self-perception on gender, who are we to overrule religious people’s self-image? Erick Erickson went a step further today with this intentionally inciting tweet:

Dear France, wrap their bodies in the carcasses of pigs. — Erick Erickson (@EWErickson) January 9, 2015

His point was that those who insist that Islamist terrorists aren’t real Muslims — the approved, “sensitive” position du jour — ought not be offended by this admittedly ugly suggestion. Not real Muslims = no need to treat them as such. Right? Shouldn’t these same people agree that, say, Guantanamo Bay guards could deny Al Qaeda detainees access to the Koran and special Halal diets without violating their human rights? How do the new “true Muslim” rules work? I’ll close by again conceding that I don’t know what the appropriate balance should be when it comes to criticizing large elements within Islam. I’m confident, however, that evading the questions I’ve raised by way of self-righteous preening (“I’m saying these things, regardless of the facts, because I want everyone to know that I’m a compassionate, non-judgmental person!”) does this important discussion a tremendous disservice, and literally endangers lives.

Yes, violent people look for violent ideologies to follow through with their values. But which breeds which? A four-year-old being brought up on violent Islamic fundamentalism is being given divine countenance and ratification for their violence and values. There is no greater rubber stamp on earth. These are the hardest nuts to crack. One can change politics with greater ease than one can leave a religion and religious framework behind. One is not threatened with the greatest punishment or the greatest reward in human conception for their political belief. Religion has that conceptual power.

Conclusion

My main conclusion is this:

Islam is defined by its creator, its holy book and the actions of its people. The first two are highly problematic, the third having large minorities with extreme views or actions. But those actions are largely on account of the first two points. Those liberals who edit out the bad parts of their holy book are cherry picking the holy book and this is diluting the true immutable word of God. If there is such a thing as a true Muslim, I think the radicals approach a more acurate version of that. This means that we need to reform the first two points to change and improve the third.

These are complex issues and to say that Islam bears little resemblance and has little causal power in the development and sustenance of Islamic fundamentalist religious violence is, to me, absurd. If all of these states were secular humanist states, would such secular humanists be able to carry out such atrocities and claim it for secular humanism? They could carry it out, but no one would be able to ascribe such violence to the notion that they were secular humanists. That would be impossible. Not so with Islam. It’s there in the texts; go read them.

I am not saying that Islam as a cadre of writing, history, and people is entirely responsible for extremist violence, otherwise all Muslims would be terrorists. Likewise all other external factors involved cannot wholly be responsible otherwise all other people with those factors at play (socio-economic etc) would be violent extremists. But there is a dangerous mix of many factors, of which Islam appears to be an important or necessary contributing cause.

Islam needs a reform; I just don’t know if one could reform a religion which is based on a holy book which is the direct word of God without making the religion some kind of syncretic, effectively secular religion with little pedigree or relevance to its core history and contemporaneous values.

If it did, though, I would be the first to be very happy about that indeed.

Pragmatics

Finally, there can be (and has been) criticism of my position that pointing out the correct causality in connecting Islamic fundamentalist terrorism with the religion of Islam may well be true but this does not help solve the problem. It is a consequentialist ethical position that though there is a truth, this truth doesn’t help and so should be suppressed.

Possibly. I don’t know whether it helps or not. An alcoholic needs to admit problems with their core behaviour before reforming themselves. In such a way, Islam needs to reform by first accepting the problematic issues within its own theological, political and moral framework.

Personally, I am interested in truth first and foremost, as a general rule of thumb. It is hard to get robust philosophy and morality without knowing the proper facts, and living on illusion. If Islam does have causal responsibility for Islamic terrorism on account of its holy book and divine characters, then I am sure as hell going to point it out. That said, I would not want my post to be used to unnecessarily drive divisive and counter-productive wedges between nonbelievers and liberal or moderate Muslims. Right-wingers may want to jump on views like this and use them for their own particular ends.

Nothing’s ever easy.

I leave you with the recent watershed remarks of the Egyptian President:

“Is it possible that 1.6 billion people (Muslims worldwide) should want to kill the rest of the world’s population—that is, 7 billion people—so that they themselves may live?” he asked. “Impossible.”

Speaking to an audience of religious scholars celebrating the birth of Islam’s prophet, Mohammed, he called on the religious establishment to lead the fight for moderation in the Muslim world. “You imams (prayer leaders) are responsible before Allah. The entire world—I say it again, the entire world—is waiting for your next move because this umma (a word that can refer either to the Egyptian nation or the entire Muslim world) is being torn, it is being destroyed, it is being lost—and it is being lost by our own hands.”…

“The corpus of texts and ideas that we have made sacred over the years, to the point that departing from them has become almost impossible, is antagonizing the entire world. You cannot feel it if you remain trapped within this mindset. You must step outside yourselves and reflect on it from a more enlightened perspective.” …

“We have to think hard about what we are facing,” he said. “It’s inconceivable that the thinking that we hold most sacred should cause the entire Islamic world to be a source of anxiety, danger, killing, and destruction for the rest of the world. Impossible.”

NOTES

Note 1 – Muir, W. (1861). The Life of Mahomet, Volume IV (pp. 307–309). London: Smith, Elder and Co.

Note 2 – David Hall (Spring 2003). “No Apologia”. New Humanist 118 (1). Retrieved 5 Aug 2012.