This article is taken from the excellent podcast Reasonable Doubts which itself borrows from source material and commentary from Tom Rees’ superb Epiphenom blog. Thanks to these two great sources for the bulk of this article.

Some interesting research has recently found out that there is a correlation between depression and religiosity. This goes against some research which suggests that religion makes people happier. It turns out that when you looks more closely, it is support structures and community which make people happy (ie not the religious content). As a tangent, it is worth noting that, other things controlled, the more confident in your beliefs, the happier you are (see terror management theory): there is a bell curve of unhappiness if you will whereby fundamentalists and hardline atheists are happy, more agnostic and wavering believers are less happy. The more secure you are, the more secure you feel against fears of death and suchlike and have better mental health.

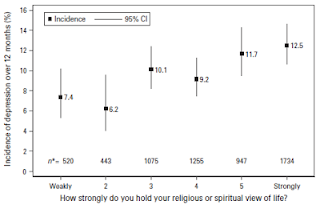

There is much of interest about this other research that looked at some 8318 non-depressed people in a longitudinal study to track moments of depression. Some 7% of nonbelievers/secularist experienced major bout(s) of depression. Active practitioners of religion showed 10.3%. Those with a spiritual worldview, 10.5%. This is not a huge effect, but a statistically significant one.

What was fascinating was that when they adjusted for known variables which play a role in depression between groups (including age, sex, education, employment, social support, past history of depression and country) they found that the religious effect vanished. One clear predictor still stood out, though: those who said they had a spiritual worldview. “Only ‘spiritual world view’ (and not active religious participation) remained a significant predictor of future depression,” stated Rees. And the country where this effect was strongest was the UK. What was interesting about this group was that the more confident this group was, the more the risk of depression went up, bucking other research. The risk of depression for weakly religious was 7.4%, whereas for the strongly religious it rose to 12.5%.

Tom Rees comments:

So religion doesn’t seem to protect people from depression, and spirituality in the absence of religious affiliation seems to be a positive risk factor – especially in the UK.

That chimes with other studies (including a recent one by King himself [see references below], and one showing that New Agers are particularly prone to delusional beliefs). What does that mean?

Probably only that people who are prone to psychological problems tend to drop out of organised religion…

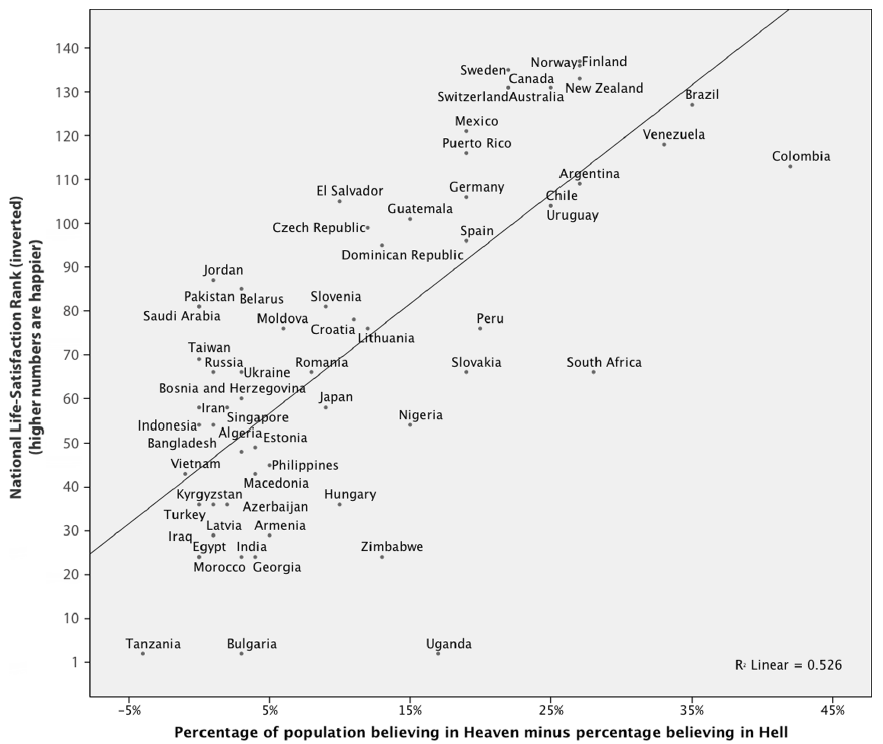

What’s going on? Well, looking at another piece of research, light may be shed. Aggregated information from dozens and dozens of studies around the world about hell and heaven and happiness. It turns out that hell has a stronger effect on negating happiness than heaven has on improving happiness. Yet, how is it that certain highly religious populations were happy and others unhappy? What they figured out is that modern Christianity has to some extent jettisoned the idea of hell and retained the idea of heaven. This over-concentration on heaven has been termed a “heaven surplus”. They took the number of people who believed in hell and took it away from the people who believed in heaven, and standardised it, and they found that the heaven surpluses had the happier populations. The ones who believed in hell had less happiness and wellbeing in their lives.

This isn’t just from the data in the countries themselves, but was replicated in the lab, where, amongst other things, priming of hell was shown to have a great effect, even on atheists; however, priming on heaven had no effect.

Problems with the data are obviously potentially existent such that cultural differences in the idea of heaven could present problems. Studies like this report what is, and not necessarily why it is so. That is the job of theorising and, to some degree, of (coherent) speculating. One speculation could also follow that countries with greater safety nets and social welfare and wellbeing are more likely to drop ideas of hell. This obviously questions the direction of causality in such findings. Which one causes the other?

Tom Rees states of this:

Nevertheless, Shariff and Aknin reckon that this might explain why hell beliefs are on the wane. In the past people believed in hell in order to keep society safe. But, with the establishment of rule-following, well policed and governed nations, the need for hell ebbed away – so people dropped their sadness-inducing beliefs.

You could debate whether belief in hell actually reduces criminality – though Sharif has previously provided evidence that it does. Arguably, all that’s important for to maintain belief in hell is that people believe that it has this effect. So perhaps people give up on hell because they stop believing that it has any effect on behaviour

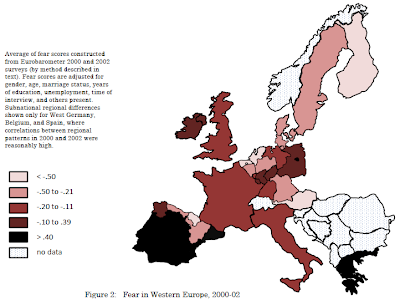

Another study which tried to isolate the causal direction of this relationship, shows a clear relationship between fear and hell. A team, led by Daniel Treisman of UCLA, wanted to create a fearfulness index of nations.  They found that fear was a social construct which didn’t match up with reality. After controlling for general fear amongst people (people who fear one thing generally fear lots of things), they saw a relationship that showed that religious beliefs were a good predictor of fear. Catholic countries were more fearful than Protestant, with the Greek Orthodox Church topping even the Catholics. More prevalent was belief in heaven or hell, as supporting the earlier research in this article. Belief in heaven pushed fearfulness back a little, whereas hell pushed it higher to a larger degree. Thus the content of religion is actually important in driving emotional behaviour. As Rees says in one of his articles:

They found that fear was a social construct which didn’t match up with reality. After controlling for general fear amongst people (people who fear one thing generally fear lots of things), they saw a relationship that showed that religious beliefs were a good predictor of fear. Catholic countries were more fearful than Protestant, with the Greek Orthodox Church topping even the Catholics. More prevalent was belief in heaven or hell, as supporting the earlier research in this article. Belief in heaven pushed fearfulness back a little, whereas hell pushed it higher to a larger degree. Thus the content of religion is actually important in driving emotional behaviour. As Rees says in one of his articles:

Those countries where a lot of people believed in Hell were more fearful across the range of potential threats. In fact, much of the apparent relationship between religious traditions and fear could be explained by the degree of hell-belief.

That chimes with some other research showing that British Christians are made less anxious by thoughts of death than are British Muslims, mainly because the Christians are less likely to believe in Hell.

So, even after adjusting for poverty, authoritarianism in the country, war, educational styles, cultural notions of masculinity and individualism, religion stayed as a prominent causal factor.

So when talking about happiness, there are mitigating aspects of religion which push up these results, such as social structures and suchlike, with the degree of confidence in your belief being second most important. But the content of your belief does indeed have an impact on your happiness; hell and all it entails makes people fearful and less happy, it seems, with secure populations appearing to drop the idea more readily.

Hell is pretty depressing. If you want to be happy, eh, just forgeddabout it.

NOTES

Aird, R., Scott, J., McGrath, J., Najman, J., & Al Mamun, A. (2009). Is the New Age phenomenon connected to delusion-like experiences? Analysis of survey data from Australia. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 1-17 DOI: 10.1080/13674670903131843

Leurent, B., Nazareth, I., Bellón-Saameño, J., Geerlings, M., Maaroos, H., Saldivia, S., Švab, I., Torres-González, F., Xavier, M., & King, M. (2013). Spiritual and religious beliefs as risk factors for the onset of major depression: an international cohort studyPsychological Medicine, 1-12 DOI: 10.1017/S0033291712003066

King, M., Marston, L., McManus, S., Brugha, T., Meltzer, H., & Bebbington, P. (2012). Religion, spirituality and mental health: results from a national study of English households The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202 (1), 68-73 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112003

Shariff, A., & Aknin, L. (2014). The Emotional Toll of Hell: Cross-National and Experimental Evidence for the Negative Well-Being Effects of Hell Beliefs PLoS ONE, 9(1) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085251

Triesman, D. The Geography of Fear

RELATED POSTS: