The sixth of the Ten Commandments says Thou shalt not kill. The funny thing is that, according to the Bible, the God who gave this commandment often told the Israelites to kill. In fact, you don’t have to go very far past the story of the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20 before you find this happening. In the story of the Golden Calf in Exodus 32, God instructs the Levites as follows:

This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: “Each man strap a sword to his side. Go back and forth through the camp from one end to the other, each killing his brother and friend and neighbour.” (Exodus 32:27, NIV)

In the book of 1 Samuel, the Bible says God commanded Saul to wipe out the Amalekites as punishment for not allowing the Israelites to pass through their land some time ago:

“Now go, attack the Amalekites and totally destroy all that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys.” (1 Samuel 15:3, NIV)

Later in that chapter, we find that God was displeased with Saul because he hadn’t carried out the slaughter to the complete extent he was ordered (he had left one human alive and some of the animals).

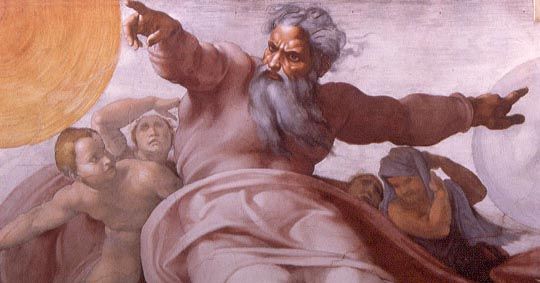

But God didn’t just get others to do his dirty work. Because Pharaoh wouldn’t let the Israelites out of Egypt, God decided a fitting punishment would be to kill all firstborn males in Egypt, whether they supported or even knew of Pharaoh’s actions or not:

At midnight the Lord struck down all the firstborn in Egypt, from the firstborn of Pharaoh, who sat on the throne, to the firstborn of the prisoner, who was in the dungeon, and the firstborn of all the livestock as well. (Exodus 12:29, NIV)

Do you see a theme here? What did the animals do to deserve this? Adding to the unfairness is the fact that the animals were already dead anyway, thanks to the plague of the livestock in Exodus 9:6…

And let’s not forget the destruction of the entire population of the planet (apart from Russell Crowe’s family and a boatload of animals) in Genesis 6-9…

So many other examples could be given, but it’s not really the point of this post to dwell on how immoral it is to wipe out entire nations, including all the men, women, children, babies and even animals. Rather, it’s to consider one common defense offered by Christians in the face of the obvious problem:

How come God says Thou shalt not kill, yet so often commands people to do just that?

Well…

The sixth commandment, many Christians claim, doesn’t say “Thou shalt not kill“, but “Thou shalt not murder”.

So, they say, it is sometimes perfectly justified to kill (women, children, animals even). It’s only against the law to murder. I’ve heard this from plenty of people. And each time I hear it, I refer them to a chapter entitled “Murder, he wrote” in Dan Barker‘s book Godless. (Barker is a former evangelical preacher who became an atheist, and is now the co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation.)

In that chapter, Barker considers the claim that the sixth commandment refers to murder as opposed to simply killing. As he points out, there are ten Hebrew words in the Old Testament translated as “kill” or variations such as “slay”, “murder”, etc, the five most common of which are:

- Muth: (825) die, slay, put to death, kill

- Nakah: (502) smite, kill, slay, beat, wound, murder

- Haraq: (172) slay, kill, murder, destroy

- Zabach: (140) sacrifice, kill

- Ratsach: (47) slay [23], murder [17], kill [6], be put to death [1].

The number in parentheses is the number of times the given Hebrew word is used in the Bible. The English words that the Hebrew words are translated to are given after that, in descending order of frequency (in the King James version – different translations would have different frequencies but I don’t imagine the orders would be drastically different).

So which Hebrew word do we find in the sixth commandment? It is ratsach. The word used for “killing” in Exodus 32:27 is haraq. So, is it true that ratsach means “murder” while haraq (and perhaps other words) refers to some kind of justified killing? Barker examines this possibility by looking at other uses of the same words. As he says, “Muth, nakah, haraq, zabach and ratsach” appear to be spilled all over the bible in an imprecise and overlapping jumble of contexts, in much the same way modern writers will swap synonyms”. Here are some examples. Unfortunately, in each of the following, I will have to use the King James version as that is what Barker used and I don’t have access to the Hebrew-English correspondence in other versions (I’m relying on someone else’s expertise here) – but obviously what’s important is the Hebrew words themselves and the contexts in which they were used.

Then Moses severed three cities on this side [of the] Jordan toward the sunrising; That the slayer [ratsach] might flee thither, which should kill [ratsach] his neighbour unawares, and hated him not in times past; and that fleeing unto one of these cities he might live. (Deuteronomy 4:42, KJV)

Then ye shall appoint you cities to be cities of refuge for you; that the slayer [ratsach] may flee thither, which killeth [nakah] any person at unawares… he that smote [nakah] him shall surely be put to death [muth]; for he is a murderer [ratsach]… But if he thrust him suddenly without enmity, or have cast upon him any thing without laying of wait, or with any stone, wherewith a man may die, seeing him not, and cast it upon him, that he die, and was not his enemy, neither sought his harm: Then the congregation shall judge between the slayer [ratsach] and the revenger of blood according to these judgments: (Numbers 35:11,21-24, KJV)

And [if] the revenger of blood find him without the borders of the city of his refuge, and the revenger of blood kill [ratsach] the slayer [ratsach]; he shall not be guilty of blood. (Numbers 35:27, KJV)

Whoso killeth [nakah] any person, the murderer [ratsach] shall be put to death [ratsach] by the mouth of witnesses: but one witness shall not testify against any person to cause him to die. Moreover ye shall take no satisfaction for the life of a murderer [ratsach], which is guilty of death: but he shall be surely put to death [muth]. (Numbers 35:30-31, KJV)

From these passages, it can be seen that ratsach is used for accidental killing, deliberate killing and justified killing. Is the sixth commandment really forbidding all of these? Apparently, even an animal can be guilty of committing ratsach:

The slothful man saith, There is a lion without, I shall be slain [ratsach] in the streets. (Proverbs 22:13, KJV)

What are we supposed to make of that? As it happens, other Hebrew words are used for prohibitions of killing in other places:

And he that killeth [nakah] any man shall surely be put to death [muth]. (Leviticus 24:17, KJV)

He that smiteth [nakah] a man, so that he die, shall surely be put to death. (Exodus 21:12, KJV)

So nakah is forbidden in those verses, yet we find godly men such as Joshua and David engaging in (supposedly) justified acts of nakah:

And when Joshua and all Israel saw that the ambush had taken the city, and that the smoke of the city ascended, then they turned again, and slew [nakah] the men of Ai. (Joshua 8:21, KJV)

For he did put his life in his hand, and slew [nakah] the Philistine [ie, Goliath], and the Lord wrought a great salvation for all Israel. (1 Samuel 19:5, KJV)

Is the biblical author saying that Joshua broke God’s commandments by killing the residents of Ai? Was David a bad man for killing Goliath?

Some Christians quote Matthew 19:18, saying that Jesus himself believed the sixth commandment to say “Thou shalt not murder“. However, as Barker points out, the Greek word used here, phoneuo, is used 12 times in the Bible, and is always translated “kill” apart from this one instance – several modern translations translate it as “kill” here, too.

But think about it. Suppose the sixth commandment really did refer only to unjustified killing. How could it ever be justified to kill children, including infants? Even if the Amalekites really were awful people, how is it justified to kill all their babies? Should the children be punished for the crimes of their parents? In Deuteronomy, we find that this is strictly forbidden:

Parents are not to be put to death for their children, nor children put to death for their parents; each will die for their own sin. (Deuteronomy 24:16, NIV)

Yet in Exodus 20 – right in the middle of the first of the Ten Commandments – we find this:

I, the Lord your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the sin of the parents to the third and fourth generation of those who hate me. (Exodus 20:5, NIV)

Well, God? What is it? Is it acceptable to kill babies because their daddy is bad or not? Is this a case of God boasting about how he flaunts his own laws? Are we supposed to be impressed?

Conclusion

So what do we make of all this? According to the Ten Commandments, God prohibited killing. But he was also often happy to command killing (and engage in it himself), even if those at the receiving end were sometimes only guilty of being born in the wrong place. Leaving aside the morality of asking some to kill (let alone wipe out entire nations of people including babies and animals), what kind of message does it send to give such contradictory commands? If I told my son not to punch his sister one day, then told him to punch her the next day, what kind of damage am I doing to his little mind? I’m sure there are plenty of bad parents out there, but wouldn’t you expect better from the supposedly perfect creator of the universe and the author of morality itself?