So I got back from a lovely week in Mexico (Olé!) to several inches of snow and Martin Sweatman’s rebuttal to my critique of his Gobekli Tepe research. One of these was dismaying.

So I got back from a lovely week in Mexico (Olé!) to several inches of snow and Martin Sweatman’s rebuttal to my critique of his Gobekli Tepe research. One of these was dismaying.

Now, Martin’s rebuttal was in a point-by-point format, and actually much longer than my original critique. Clearly, a point-by-point she-said-he-said-she-said response would be tediously ponderous and virtually unreadable, so I’ve chosen for the most part to summarize and respond to some major points in this post, and then to comment separately on his statistical claims.

INDEPENDENT CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS

Martin takes exception to my claim that different areas of the world pursued independent paths of development, when at some point in the history of Homo sapiens, before our ancestors dispersed out of Africa, they must all have shared one language and mythology. He backs this up with reference to scholarly works on comparative mythology and linguistics, with particular reference to Proto Indo-European. He further dismisses any citing of the archaeological record on my part as “just (my) opinion.”

Having lived with a phonetician/linguist for nearly forty years, I have osmosed quite a bit about historical and comparative linguistics. Proto-Indo-European has a time depth of about 7-8ky at most; the majority view places the urheimat in the steppes north of the Black Sea, beginning to spread and diversify from around 4000 BC. This means that the huge diversity of the Indo-European language family, from English to Urdu, from Welsh to Farsi, from Russian to Hindustani, has taken only between six and seven thousand years to develop. I do not think Martin has any idea how rapidly languages can diversify when populations split up.

It is also possible he is not aware of how many proto-languages are proposed. Anatolia’s status is still disputed, but the Levant was in the area of Proto-Afroasiatic, which includes Akkadian and the later Semitic languages, and has nothing to do with PIE. (Sumerian was an isolate.) And PIE and PAA are only two of the numerous superfamilies already spread across the globe at the time of the Neolithic transition. Any hypothetical monogenetic source language had long since diversified in the tens of thousands of years since our ancestors spread out of Africa, and I suspect the same is true of mythologies. Proto-PIE mythology, incidentally, has nothing to do with asterisms, and bears no resemblance to Martin’s proposals, so I’m not sure why he brought it up.

Differences among culture areas across the world are strikingly visible even in the early Holocene, in terms of material culture, art styles and media, subsistence strategies, technology, methods of dealing with the dead, and asterisms that can be inferred from internal evidence and later narratives. Ignorance of the archaeological evidence does not mean the evidence can be ignored.

IMAGE IDENTIFICATION

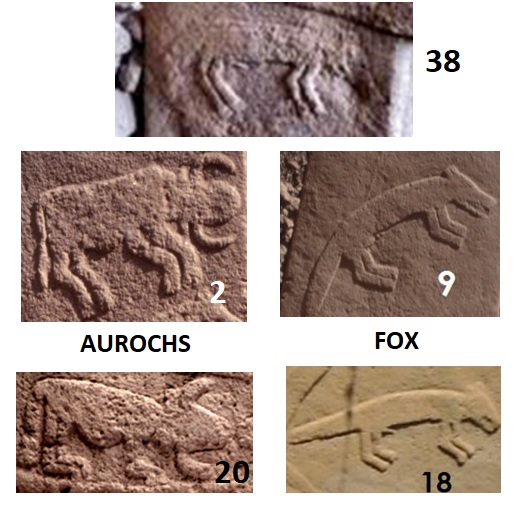

A good part of Martin’s rebuttal dealt with my specific criticisms of how he dealt with the images and their identifications. These are important, because Martin’s rankings, and therefore his statistical analysis, depend on the identifications being both convincing and consistent. Consistency is crucial, in my opinion, because otherwise a significant element of subjectivity and special pleading comes into play. If the same image is identified in several different ways according to the researcher’s convenience, then the risk of GIGO increases unacceptably. Two examples:

The Fox

Martin interprets this image in three significantly different ways. First as a wolf, identified as the constellation Lupus, one of the eight figures on Pillar 43 that form the foundation of his statistical analysis. Second, as a fox, which he equates with the northern asterism of Aquarius, and uses as one link of a tangled chain of logic that ultimately verifies the importance of the Taurid meteor stream to the Gobekli Tepe astronomers. Third, he interprets a damaged image on Pillar 38 as an aurochs, also a critical element in the Taurid-radiant argument, and doubles down on that identification in his rebuttal:

It could easily be an aurochs. However, as the head is damaged, this is uncertain. We comment on this in the paper….In this case, I agree, Pillar 38 is so damaged that it is hard to be sure about these symbols. It is rational, though, given our preceding statistical case, which provides the necessary confidence, to interpret it as an aurochs. And, indeed, I personally think the excavators have got this one wrong. It genuinely looks more like an aurochs than a fox to me.

Well, let’s have a look (see below). The characteristics of other aurochs images: pot-belly, S-curved front legs, no penis, narrow tail hanging straight down, rounded muzzle. The characteristics of other fox images: flat belly, V-shaped front legs, penis, thick tail held away from the body, square muzzle. Image on Pillar 38: flat belly, V-shaped front legs, penis, thick tail held away from the body, square muzzle (clearly visible, despite the damage, on the illustration in Martin’s own paper). Furthermore, the area of damage is not large enough to accommodate the diagnostic horns of the aurochs.

It’s a fox. Identifying it as three different animals and two separate asterisms is…well, questionable. What does the fox say? Nothing much. It’s in therapy right now, with a nasty case of identity crisis.

The Lion

The little critter by the middle “handbag” at the top of Pillar 43, with a square muzzle and a long tail across its back, most closely resembles other images of a fierce feline predator. Martin admits this—indeed, the lion is said to be the better match in his ranking table—and yet he persists in identifying the image as an ibex, gazelle, or charging quadruped, equated with Gemini, in both this and his second paper. The lion/leopard, on the other hand is firmly equated with Cancer. But Martin’s alternate identifications just seem strange: ibexes have horns and short tails; gazelles have short tails and gracile muzzles. Could the beast be a long-tailed horse? Apparently not, because Martin later equates the horse with Leo. I am mystified as to why he rejected the lion in the first place, as that is so clearly what it is. At any rate, it gives us another example of the same image being equated with two separate asterisms, in this case Gemini and Cancer.

In this section, I’ll indulge in a little point-by-point discussion. Martin complains that I assume the animal symbols at GT are only ever used as star maps, whereas he argues they are…

…symbols, representing constellations, that can be used flexibly to convey different ideas. Yes, sometimes they are used together to represent a map of the sky. At other times, they are used to represent a date using precession of the equinoxes, and at other times they are used to represent the track of the radiant of a meteor stream. Other uses might come to light with further excavations.

Actually, I assumed that Martin would be consistent in his interpretations, especially as his statistical analysis depends on them. Indeed, he reads Pillars 2, 38, and 43 as star maps—but where the star-map interpretation is untenable, he apparently reserves the right to assign any meaning convenient to his thesis. I have 100% confidence that Martin will always be able to justify his speculations, simply by moving the goalposts.

As they are symbols that can be used flexibly, they can be thought of as an early kind of proto-script. So, for example, one tall bird can have the same meaning as a group of tall birds: Pisces. There is no reason to assume otherwise.

Oh my. There is every reason to assume otherwise. For example, Martin’s statistical analysis of Pillar 43 depends in part on Pisces matching the “bent bird” more closely than any other possible animal figure. But how do the three birds on Pillar 38 (two “tall birds” and one completely different bird) match that asterism, in a context which is also explicitly treated as a sky map? And in what kind of script, proto or otherwise, does A=AAB?

I notice you do not go through Pillar 2 in detail, which is a much clearer demonstration of our decoding.

Pillar 2’s “decoding” is only significant when paired with Pillar 38. If Pillar 38’s decoding is invalid (which it is), then the comparison with Pillar 2 is meaningless, and the entire tower of speculation about the Taurid radiants falls down. (Which it does.)

THE STATISTICS

Throughout his comments and rebuttal, Martin has returned again and again to what he considers his trump card: his claim of a slam-dunk 99.99999999 etc percent probability that his interpretation is the only correct one. He has repeatedly challenged me (and many others) to produce my own rankings, as the only way of disputing his stats. It does not matter, apparently, that his thesis is detached from the archaeological evidence. It does not matter that it depends on an initial assumption that the images are asterisms, an assumption which his method does not test. It does not matter that his input is inconsistent, naive, and subjective—the robustness of that high probability is supposed to cover all sins. Well, I do have something to say about this, but I shall reserve it for a separate post.

My comment on Martin Sweatman’s statistical analysis can be found here: What does the Bunny Say?