So why do academic archaeologists reject sexy, exciting ideas like the Lost Civilization, Atlantis, ancient aliens, coded messages in the dimensions of the Great Pyramid, and so forth?

So why do academic archaeologists reject sexy, exciting ideas like the Lost Civilization, Atlantis, ancient aliens, coded messages in the dimensions of the Great Pyramid, and so forth?

According to archaeologists, it is because these ideas have no evidence for them, and considerable evidence against them. But according to the fans of such ideas—let’s call them “alternos”—it is because archaeologists are both close-minded and deathly afraid to step out of line for fear of damaging their careers—academic archaeology is an orthodoxy, they say, a belief system, virtually a cult, actively working to suppress new ideas that might disturb the accepted dogma.

I get a lot of that sort of thing in the comments section when I write on pseudoarchaeological topics. It is…boring. Ignorant. Kind of sad. If only these folk would read a few books about how archaeology actually operates, instead of the collected works of Hancock, von Daniken, and that lot. So here’s what I’m going to do: a blanket response, partly excerpted from a chapter I wrote for this book, to which I will link any time a commenter plays the orthodoxy card, because life is too short to keep on rebutting this nonsense. The fact is, the existence of an archaeological orthodoxy is an article of faith among the alternos, but it is a myth.

1. How archaeologists are made.

Alternos complain that potentially valuable ideas from their camp are ignored because their proponents do not have that union card we call a degree in archaeology. I will freely admit that some PhDs are idiots, and some alternos are brilliant. Nonetheless, that bit of paper does guarantee something very important: that its holder will have spent a number of overworked, underpaid years as a student, intimately exposed to the archaeological database and its context.

That will include the history of the discipline, a good grasp of previous research, a crucial grounding in method and theory, and a fair amount about related disciplines: geology, biology, anthropology, physical anthropology, history, classics, statistics, etc. And that is even before one starts to specialize. To put it simply, archaeologists have to know a lot more about archaeology than the contents of a few books, websites, or television documentaries about Atlantis and ancient aliens. That hard-won broad-based expertise counts for something. A guy with a pair of pliers may do a perfectly adequate job of pulling teeth, but I personally would go to a dentist with professional credentials. The principle is similar.

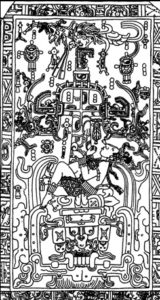

Suppose an alterno points out, with great excitement, that a certain ancient relief represents a spaceman at the controls of a rocket ship. An archaeologist who has spent years studying hundreds of similar reliefs says no, it doesn’t, and tries to explain the details of the iconography in their full cultural context. The alterno then accuses the archaeologist of being unable to accept new ideas that challenge entrenched dogma. In the world of the alternos, it seems, knowing about what you’re talking about is actually a disadvantage. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Suppose an alterno points out, with great excitement, that a certain ancient relief represents a spaceman at the controls of a rocket ship. An archaeologist who has spent years studying hundreds of similar reliefs says no, it doesn’t, and tries to explain the details of the iconography in their full cultural context. The alterno then accuses the archaeologist of being unable to accept new ideas that challenge entrenched dogma. In the world of the alternos, it seems, knowing about what you’re talking about is actually a disadvantage. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Certainly we should not, and do not, uncritically accept the pronouncements of PhDs, nor automatically throw out the suggestions of those without them. In fact, self-taught scholars, passionate amateurs, and people whose formal expertise is in fields other than archaeology have a more honorable place in the discipline than the alternos would have the public believe, as long as their evidence is compelling.

2. How archaeology operates.

Among alternos, hostility and derision towards the academic mainstream is a recurrent theme. The alternos invest themselves with the appeal of the underdog, and the glamour of the maverick. They describe professional academic archaeology as the next thing to a priesthood: elitist, dogmatic, pedantic, held back by investment in the orthodox paradigms, conspiring to suppress dissent.

This is simply not true. The last century of archaeology has been colorful and action-packed—healthy controversy, waves of self-criticism, several fundamental paradigm shifts, the development of whole new subdisciplines and technologies, the rise of middle-range theory, and generation after generation of—believe me—hyperactive archaeologists pushing back the boundaries, and looking for new ways to find out about the past.

There is no pressure to toe any party line. Peer review serves mainly to keep you honest—that is, to make sure you don’t overstep what your evidence will support. But you would not advance your career in archaeology by simply parroting an officially approved orthodoxy; you would advance by doing good research and providing new insights, and often by revising or even contradicting the currently dominant models.

There is no pressure to toe any party line. Peer review serves mainly to keep you honest—that is, to make sure you don’t overstep what your evidence will support. But you would not advance your career in archaeology by simply parroting an officially approved orthodoxy; you would advance by doing good research and providing new insights, and often by revising or even contradicting the currently dominant models.

In fact, there is no monolithic orthodox narrative in archaeology – there are numerous schools of thought bashing away at the mysteries of the past, and sometimes at each other. And the process is not the stodgy, dignified, and tight-lipped process envisioned by the alternos. It’s a little more like, say, the Three Stooges doing their tax returns: much head-scratching, eye-poking and yelling of contradictory directions, but in the end, a provisional consensus may emerge. No, archaeology does not suffer from stodginess or blindness. New ideas are being incorporated all the time.

3. Déjà vu all over again.

Still, the alternos accuse archaeologists of being closed to new ideas. The irony is, the alterno-archaeological theories they propose are not new. Some of the theories are repackagings of old pseudoarchaeological standbys that have been repeatedly debunked for decades—Bimini, the Newport Tower, the Great Pyramid, Easter Island, Macchu Picchu, Baalbek, etc, etc, etc. Some of the theories are mainstream hypotheses that were falsified and abandoned long ago, for good reason. For archaeologists, it becomes a wearisome round of “déjà vu all over again.“

Take the case of the Lost Civilization—an advanced global super-civilization that is said (by alternos) to have flourished before the end of the last Ice Age until its catastrophic destruction in about 10,500 BC. Its survivors scattered themselves across the globe as culture-bearers, to seed new civilizations and leave coded  messages about the lost glories of the past in the legends and monuments of its successors. It is bunkum. And it relates to a model of world history that was long ago abandoned by archaeology.

messages about the lost glories of the past in the legends and monuments of its successors. It is bunkum. And it relates to a model of world history that was long ago abandoned by archaeology.

Nineteenth-century archaeological theory held that civilization arose in one area of the world, and was then spread by culture-bearers, migrations, and invasions. Then, as the discipline developed and the database began to build up, it became clear that different areas of the world had followed independent trajectories towards food production and social complexity, processes that can be traced in often exquisite detail in the archaeological record. The idea of a single source for “civilization” was necessarily abandoned, in favour of a much more fascinating and diverse narrative of the peopling of the Earth, a narrative that continues to develop as more data come in.

Archaeologists reject the “Lost Civilization” for good reasons. First, we have a reasonably solid idea of what was happening in the relevant time period, in terms of detailed archaeological sequences backed up by solid evidence. Second, we know what was not happening in the relevant time period: a far-flung and technologically sophisticated complex society that somehow managed to leave no credible archaeological remains. Additionally, every new “site” that is proposed as evidence—Gunung Padang, Visoko, Yonaguni, a score of Atlantises—turns out to be a dud.

But I would like to point this out: if an unequivocal lost city of the Lost Civilization were miraculously discovered, we archaeologists would not be trying to suppress the knowledge and hide it from the world. Are you kidding me? The little kernel of Indiana Jones that lurks in every archaeologist would be tickled pink. We would be fighting each other to get onto the dig. Careers and reputations would be made, funding would be titanic, books and articles and PhD theses would abound. We would have to rethink a huge chunk of the current consensus, which would be enormous fun and probably create some jobs. It would be fabulous. In summary, the alternos are not only ignorant of archaeology—they are woefully ignorant of archaeologists.