It is an attractive vision: a golden city of high culture that flourished long ago, but which came to a terrible end through its pride and greed, and now lies in ruins under the sea. All of which makes it, not only a thumping good story, but a perfect allegory for hubris, otherwise known as getting too big for your britches; or for entropy, the tendency of things to fall apart. But is it history or allegory? Folk-memory or a fiction? I’ll talk about that in this series, sparked off by recent discussions on Gunung Padang.

It is an attractive vision: a golden city of high culture that flourished long ago, but which came to a terrible end through its pride and greed, and now lies in ruins under the sea. All of which makes it, not only a thumping good story, but a perfect allegory for hubris, otherwise known as getting too big for your britches; or for entropy, the tendency of things to fall apart. But is it history or allegory? Folk-memory or a fiction? I’ll talk about that in this series, sparked off by recent discussions on Gunung Padang.

For the Atlantis narrative, whether fact or fiction, has taken on a life of its own in our times. Many books have been written around it; it shows up in movies, television, computer games, mystical cults, even a tragic opera and an attempted musical. Its magical name has been bestowed on all manner of things, from bouncy castles to luxury hotels and even a space shuttle (though calling a space shuttle after a place that vanished catastrophically seems to me as tactful as naming it after the Titanic.) It has spawned generations of searchers for its watery grave, or its coded residue in the remains of known ancient civilizations.

In short, Atlantis has a complex resonance in modern culture, not just for its classical connotations, but also for its strands of mysticism, ancient glamour, and lost wisdom. Over the centuries, as well, the legend has been expanded to include two other sunken continents, Mu and Lemuria, each with its own story. It is worth going back to the origins of the narrative, and then to trace it forward to see where and how all those strands joined the evolving tapestry. Here we go.

The Origin

The first mention of Atlantis is in the writings of Plato, preeminent Greek philosopher living in the 5th to 4th centuries BC: pupil of Socrates, mentor of Aristotle, author of The Republic and many other works of philosophy and political theory. The relevant works are two that were written late in Plato’s life, c.360 BC: Timaeus and Critias. They are in Plato’s favoured format, dialogues on matters of mutual interest, in this case involving Plato’s old mentor, Socrates, and three other aristocratic Greeks: Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates. Timaeus is set on the day after the dialogue presented in Plato’s Republic, which described the ideal political state, though the latter was written about twenty years earlier and involved different speakers. With Timaeus, Plato was evidently setting out to write a trilogy that would expand upon and illustrate some of the themes of The Republic; alas, Critias was left unfinished, and the third projected dialogue, Hermocrates, was never written.

The first mention of Atlantis is in the writings of Plato, preeminent Greek philosopher living in the 5th to 4th centuries BC: pupil of Socrates, mentor of Aristotle, author of The Republic and many other works of philosophy and political theory. The relevant works are two that were written late in Plato’s life, c.360 BC: Timaeus and Critias. They are in Plato’s favoured format, dialogues on matters of mutual interest, in this case involving Plato’s old mentor, Socrates, and three other aristocratic Greeks: Timaeus, Critias, and Hermocrates. Timaeus is set on the day after the dialogue presented in Plato’s Republic, which described the ideal political state, though the latter was written about twenty years earlier and involved different speakers. With Timaeus, Plato was evidently setting out to write a trilogy that would expand upon and illustrate some of the themes of The Republic; alas, Critias was left unfinished, and the third projected dialogue, Hermocrates, was never written.

Timaeus makes only passing reference to Atlantis, as an illustration of the idealized state discussed in The Republic, but the ideal state is not Atlantis—it is the virtuous Athens of the distant past. Critias’s illustrious collateral ancestor Solon, visiting Egypt, was told the story by a rather patronizing Egyptian priest and passed it down orally through his family. The tale goes that, 9000 years before, Athens liberated the Mediterranean world, including Egypt, from the tyranny of an evil empire situated on an island in front of the Pillars of Hercules, generally recognized as Gibraltar – an empire that was then destroyed by earthquake and flood. Then Timaeus takes over and spends the rest of the dialogue delivering a monologue on creation and the nature of things.

The next day, it is the turn of Critias to deliver a monologue. He first describes the noble Athens of 9000 years ago; then he moves on to describe Atlantis and its origins, founded by the god Poseidon and settled by Poseidon’s children out of a mortal wife, Kleito. The capital is described as a city of rings of water and land around the original hill where Poseidon had first bedded Kleito, on a large, fertile plain fringed with mountains and abounding in all good things, including elephants. The continent on which it stood was ruled by descendants of the original ten kings, the sons of Poseidon out of Kleitos, who met regularly in the central temple of Poseidon to sacrifice a bull and work out their decrees.

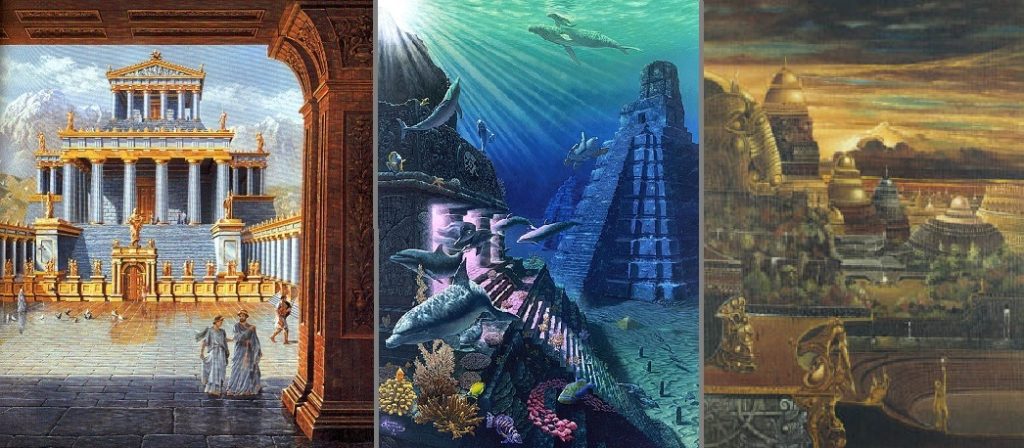

Through the generations, so the story goes, Atlantis became ever grander and more fabulous, with palaces and towers, great statues, harbours, and bridges over the broad canals that still divided the city into concentric rings. The vague nature of Plato’s visual descriptions has given modern artists, writers, and alternative scholars a free hand in gorgeously envisioning it. In general, their visions of lost Atlantis break down into three broad categories:

- The Greekoid, a generic romanticized classical Mediterranean/Aegean vibe with a dash of ancient Egypt.

- A vaguely Mayan style, where the pyramids are stepped.

- A fantasy and science fiction model, with grand high technologies and sometimes a kind of Conan-the-Barbarian-meets-Flash-Gordon effect.

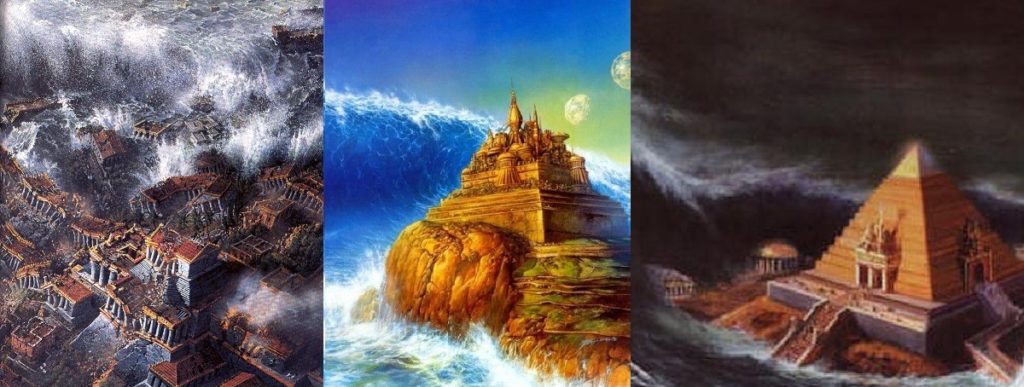

This is how Atlantis is now popularly perceived—a Garden of Eden with Doric columns, or an advanced civilization with wonderful powers—but Critias’s story continues. After a time, something happened. The god’s contribution to their gene pool was diluted over the generations, and the human portion became dominant. The civilization slid into decadence and cruelty, the population into avarice. Atlantis became the Axis of Evil – but the good guys, the primeval Athenians, were able to defeat them in battle and liberate all the nations they had enslaved, including Egypt, just before the evil empire was finished off by earthquake and flood. (The noble Athenian armies were destroyed at the same time, which I would consider a bit of a mixed message.)

The destruction is described only in Timaeus, the first dialogue; the second, Critias, goes into detail on the physical layout of the island, but the story breaks off just as Zeus begins to explain what he intends to do about the wicked Atlanteans – rather as if Plato got writer’s block. Anyway, he never finished it, and he never wrote the sequel. But here is how the destruction is described in Timaeus:

But afterwards [that is, after the Athenians had already defeated the Atlanteans] there occurred violent earthquakes and floods, and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea. For which reason the sea in those parts is impassable and impenetrable, because there is a shoal of mud in the way; and this was caused by the subsidence of the island.

So, according to Plato’s mouthpiece character Critias, the result was not a picturesque ruin at the bottom of the sea, but an unnavigable mudbank. And that’s the basic story, the sole presentation of this narrative in ancient literature. The first question has to be – what was Plato doing here?

(1) Was he telling the truth as he knew it? Passing on a true account of a genuine historical event, the memory of which was husbanded by the Egyptians for nine millennia before they thought to mention it to Solon? If so, it is very odd there is no record of it in any of the extensive writings we have from Ancient Egypt. Not a word.

(1) Was he telling the truth as he knew it? Passing on a true account of a genuine historical event, the memory of which was husbanded by the Egyptians for nine millennia before they thought to mention it to Solon? If so, it is very odd there is no record of it in any of the extensive writings we have from Ancient Egypt. Not a word.

And if the dates given by Plato are taken at face value, then they give us a testable archaeological claim, not for Atlantis, but for Athens—and the claim fails the test. There is no support whatsoever for such an early dating of an urban society in the region of Athens; at 9600 BC, there are just odd traces of Mesolithic wanderers around the plains of Attica. In fact, even the Greek Neolithic does not get into full swing until the 6th millennium BC at the earliest. Nor does Critias’s topographical description of Attica c.9600 BC—an uneroded plain that was stripped to its bones by Plato’s time by successive disasters—match the reality.

(2) Was Plato lying? This is a funny one. No archaeologist or classicist I know would take that view, and yet that is the straw man held up by some alternative scholars – that anyone who chooses to see the story as less than veridical is slandering the good name of Plato. Some of them get a bit worked up about it. But nobody would call me a liar for setting my novels in a fantasy world I just made up – they’d call me a novelist. Which segues neatly into the next possibility.

(3) The story was a fictional device, cleverly constructed by Plato for the purposes of a philosophical argument. Remember Plato was not setting out to write history; he was putting words into the mouths of four dead guys as part of a recognized literary genre. Nor does anything suggest that contemporary or later classical authors took it as anything but allegory – in fact, Strabo quotes Plato’s pupil Aristotle as saying of Atlantis: “The one who invented it also destroyed it,” meaning Plato. It makes sense as a plot device: Plato needed an idealized state, and he needed good guys and bad guys on a cosmic-quality stage. It did not hurt that his good guys were the primeval Athenians.

There is also the question of one of the dead guys, Critias himself. He is based upon a real person, a noted writer and aristocratic politico, also a violent demagogue who played the part of Robespierre in the civil wars at the end of the fifth century BC. Plato may also have been drawing on a previous Critias, but either one would introduce an anachronism into any literal reading. And I have to ask: how would Plato have heard the story, if indeed it was passed down from Solon—the latter Critias was killed in battle more than forty years before Critias was written, and there is not a whisper of Atlantis before or in the intervening years. The parsimonious explanation is that Plato made up all those delectable details himself, like any good fictional world-builder.

There is one other concept I’d like to introduce here, a widespread attitude in the ancient world, which still has echoes today: primitivism. Forget the usual connotations of “primitive,” as in dirty, hairy and heathen – in fact, think the exact opposite. Every society whose stories we can access had creation and origin myths,  many of them with something interesting in common – they hark back to a time at the beginning of the world, when God or the gods had just finished the labour of creation, and the world and the newly spawned human race were spotless and perfect, like new toys on Christmas morning.

many of them with something interesting in common – they hark back to a time at the beginning of the world, when God or the gods had just finished the labour of creation, and the world and the newly spawned human race were spotless and perfect, like new toys on Christmas morning.

But just as those new toys would immediately start to collect dirt and scratches, the world and the people began to deteriorate. Something happened—people got too noisy or ambitious or greedy, or the gods became jealous of their own creation, or somebody made the dumb mistake of eating forbidden fruit. Something happened to drag humanity out of the Edenic state of perfection, and it has been downhill ever since. And not just downhill, but occasionally underwater. The Atlantis story has the earmarks of a primitivist narrative, which means you do not necessarily have to look for a physical or historical source for Plato’s story material. He was using a model already familiar to his audience, because it was a current default explanation for human history.

(4) There is yet a fourth possibility – that Plato drew on folk memories of an actual disaster, and gave it a mythical framing and a political moral. It is on this basis (and the basis of the first possibility) that a number of both alternative and mainstream scholars go looking for Atlantis – and, as we’ll see, a hilarious number of them have actually found it.

Next: the legend grows.