Way, way back at the beginning of time—okay, back when I was twelve and in Grade Seven—I did a science fair project about flying saucers, using that idiot George Adamski as a serious resource. Fortunately it was in the dark ages before the internet, and this embarrassing youthful indiscretion sank without a ripple when I began to develop my skeptical spidey senses.

Way, way back at the beginning of time—okay, back when I was twelve and in Grade Seven—I did a science fair project about flying saucers, using that idiot George Adamski as a serious resource. Fortunately it was in the dark ages before the internet, and this embarrassing youthful indiscretion sank without a ripple when I began to develop my skeptical spidey senses.

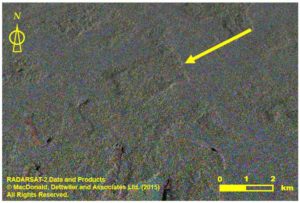

Times have changed. There was this teenager in Quebec named William Gadoury who also did a science fair project—rather, he did ground-breaking archaeological research that confounded the experts, went viral, and gained world-wide attention. He discovered, it seems, that the Maya laid out their entire civilization, hundreds of cities and towns over an area of thousands of square miles, in order to map the Mayan constellations onto the Earth—big cities for the brightest stars, smaller sites for the dimmer ones. But lo, there was an empty space on the ground that corresponded to a star in heaven—ergo, a heretofore lost Maya city must still be out there in the unexplored jungle, waiting to be ground-truthed. And lo again, that lost city showed up on satellite photos, complete with pyramid, possibly the fifth largest Maya city ever, validated by an actual grownup with expertise in remote-sensing technology.

It was the kid’s science fair project, but you’d think it was in the running for a Nobel prize. The story broke first in a Montreal newspaper, was picked up by the CBC and the foreign press, and took off around the world. I suppose the angle was irresistible: fifteen-year-old schoolboy discovers a lost city and puts professional scholars to shame without even having to miss dinner. He was feted and vaunted and interviewed and made much of. He was invited to give a presentation to the Canadian Space Agency, which had kindly provided him with the satellite photos. He won the gold medal at the science fair. He was chosen to go to the 2017 international science fair in Brazil. The media adored him.

But then the Mayanists started to weigh in—you know, the archaeologists and  epigraphers and other scholars who actually know something about the area, the history, and the culture. Not surprisingly, they were unimpressed. While trying to be tactful about the kid, they were unanimous in rejecting his claims, for a very large number of very good reasons. For one thing, the area pinpointed for the lost city was already being worked in, and the so-called pyramid and structures were fallow fields. But never mind the awkward details: the basic premise was a priori not just impossible, but actually ridiculous.

epigraphers and other scholars who actually know something about the area, the history, and the culture. Not surprisingly, they were unimpressed. While trying to be tactful about the kid, they were unanimous in rejecting his claims, for a very large number of very good reasons. For one thing, the area pinpointed for the lost city was already being worked in, and the so-called pyramid and structures were fallow fields. But never mind the awkward details: the basic premise was a priori not just impossible, but actually ridiculous.

This was the basic premise: that the Maya (but starting with the Olmec, as far as I can tell) sited their settlements according to one gigantic master plan based on the constellations, rather than on boring local considerations like resources, trade routes, and defence. But think about this scenario for a moment. You would need the entirety of the Maya lands (325,000 square kilometres, according to young Mr. Gadoury) to be under one overarching authority, with the power to tell the people where to build big cities to stand for bright stars, and where to build smaller settlements to stand for dim stars. You would need this central authority to be in place for well over a thousand years, right through Post-Classic times, keeping close control over the settlement patterns. Woe betide if a minor centre tried to outgrow the second-rate star it was meant to represent! You’d need the technical and technological wherewithal to survey and lay out your star map on the grandest of all scales, across hundreds of miles of difficult terrain, and to a high degree of accuracy.

None of this sounds anything like the Maya lands of the archaeological record: a restless patchwork of competing polities, frequently at war with each other, with evolving local agendas and dynasties and regional variations in rituals and beliefs, and cities and settlements that waxed and waned over the centuries. All these matters have been extensively studied; there is, as well, a rich literature mapping the relationship of the Maya to their sacred landscapes, which incidentally have nothing to do with the stars. For that matter, though Mayan astronomy is a thriving area of research, their constellations are lost in the mists of time. There are no Mayan star maps per se, and certainly none in the Madrid Codex where Mr. Gadoury claimed to find them. Nor did the Maya worship the stars, as the kid seems to think. So what was he mapping, and where did he get his ideas?

None of this sounds anything like the Maya lands of the archaeological record: a restless patchwork of competing polities, frequently at war with each other, with evolving local agendas and dynasties and regional variations in rituals and beliefs, and cities and settlements that waxed and waned over the centuries. All these matters have been extensively studied; there is, as well, a rich literature mapping the relationship of the Maya to their sacred landscapes, which incidentally have nothing to do with the stars. For that matter, though Mayan astronomy is a thriving area of research, their constellations are lost in the mists of time. There are no Mayan star maps per se, and certainly none in the Madrid Codex where Mr. Gadoury claimed to find them. Nor did the Maya worship the stars, as the kid seems to think. So what was he mapping, and where did he get his ideas?

Well, Mr. Gadoury is hoping to publish his research, but until then it is difficult to tell exactly what his sources were; there are indications, however, that his starting point was squarely inside the pseudoarchaeological literature. His interest began with the 2012 “prediction” of the end of the world, which was a staple of the pseudo-side; mapping the stars onto hapless archaeological complexes is a game long played by pseudo-scholars like Robert “Orion Correlation” Bauval and Graham “As Above, So Below” Hancock. Indeed, Mr. Gadoury makes a telltale admission: a claim that this same technique can be used to illuminate Aztec, Inca, and Harappan settlement patterns, the kind of claim that is well within the pseudo tradition and links back to wild assertions of a vanished pre-Neolithic supercivilization. And his response to the debunking by professional Mayan scholars is chillingly familiar: the archaeologists are just jealous, with minds that are closed to new ideas. Erich von Daniken could not have said it better.

BUT – you can’t blame the kid. William Gadoury was thirteen when he had his bright idea, and fifteen when it went viral. At about that age, remember, I was halfway convinced that George Adamski visited Venus in a flying saucer piloted by a blonde bombshell. Gadoury is obviously a bright lad with a talent for research—but what he did was straight out of the pseudoarchaeologists’ playbook, and should not have been confused with science. But if you can’t blame the kid, who can you blame?

Well, where were the grownups? Science teachers, science fair advisors and judges, his enablers at the Canadian Space Agency and his remote-sensing mentor: did none of them see how patently silly the hypothesis was, nor steer him to some actual archaeologists for a reality check before he got too invested in his grand idea? It seems they were all so bedazzled by the boy’s dedication and the project’s faux-scientific veneer that they failed to recognize the GIGO factor and the pseudoscientific substrate—and thus, they failed in their duty to the boy.

How about the media who made a huge story out of the “discovery” before checking to see whether it made any sense at all, and then spread it globally? Without them, he may have been able to brush this nonsense off in due course, as easily and anonymously as I brushed off Adamski. Now he’s committed. I hope, I really do hope, he can break free.