The Lateral Truth: An Apostate’s Bible Stories was first brought out in 2007 by Scroll Press, a small publisher in Prince George, BC, started up by an estimable member of UNBC’s English Department. Alas, Scroll went out of operation last year, which freed me up to bring out a new edition. But at first publication, Scroll interviewed me for the website with some really excellent questions, and here—cut down and updated—are my replies.

The Lateral Truth: An Apostate’s Bible Stories was first brought out in 2007 by Scroll Press, a small publisher in Prince George, BC, started up by an estimable member of UNBC’s English Department. Alas, Scroll went out of operation last year, which freed me up to bring out a new edition. But at first publication, Scroll interviewed me for the website with some really excellent questions, and here—cut down and updated—are my replies.

Why did you write this book?

I could not avoid writing this book. I was a natural-born atheist in an Evangelical Baptist fundamentalist family, surrounded by born-again convictions and old-fashioned cover-to-cover tearstained-leaves literalism. I could not buy into any of it, myself, but I was both enthralled and appalled by the stories in the Bible, not to mention confused by the mixed messages they sent.

There were three good reasons, however, to keep silent about my inability to believe: first, because it would upset my lovely parents; second, because I would get prayed over, which was embarrassing and repugnant; and third, because I was not sure I wouldn’t get sent to hell for not believing in a god. Dawkins is right about the power of that fear. I even hid my atheism from my irreligious friends, most of whom probably saw me as a right fundamentalist fanatic. It was a closet I did not come out of until I was about twenty.

But while I was growing up, I took a keen (and later a professional) interest in history, archaeology, and anthropology, and ran across many fascinating themes: how mythologies are made, for example; how dogma can seduce, subvert, and destroy, and how one man’s barbaric superstition may be another man’s holy writ. When I eventually shambled into being a writer, it was only a matter of time before I got the urge to try weaving all these strands together. The ideas were already there, rooted in questions I’d had the tact and good sense to keep quiet about as a child.

So why break silence now? This book’s proximate cause is that I am worried by how the world is going, amazed by the upsurge of religious magical thinking, dismayed by the growing power of fundamentalisms of various pernicious stripes, not all of them involving a god. At a time when we humans, as a collective, need to be particularly rational, we appear to be getting particularly stupid. These stories could be considered my small contribution to the chorus of humanist voices crying in the wilderness.

how the world is going, amazed by the upsurge of religious magical thinking, dismayed by the growing power of fundamentalisms of various pernicious stripes, not all of them involving a god. At a time when we humans, as a collective, need to be particularly rational, we appear to be getting particularly stupid. These stories could be considered my small contribution to the chorus of humanist voices crying in the wilderness.

Describe your creative process writing this book. Specifically, how did you conceive this idea?

As I said above, The Lateral Truth was a book waiting to happen; but it finally germinated almost by accident, when we were living in Hong Kong. Every summer, the South China Morning Post and RTHK, Hong Kong’s English-language radio station, would combine to sponsor a short story contest on a given theme. In 1993, the theme was FIVE YEARS AFTER—and I had the idea of writing about Adam and Eve five years after their expulsion from Eden, which turned into an early version of “Omphalos.” (It didn’t win.)

Over the next few years, I stuffed work on the Bible stories into the interstices of other writing and research projects, plus the upheaval of moving back to Canada, taking up formal teaching, and so forth. By 2000, I had five stories in draft form, plus fragments of and notes for eight others; and in 2001, the Alberta Foundation for the Arts (to whom much gratitude) gave me a generous grant that allowed me to concentrate on Lateral Truth for about eight months. It was a great time, divided about 50/50 between research and writing, and all of the stories except “Death of a Pagan” and the last two sections of “The Trickster” were in good draft form by Christmas. The latter stories were finished gradually by 2004, in tandem with the long and painful process of polishing the others, trying to find a publisher, and taking a last fling in archaeological fieldwork in the Sudan.

As for the “creative process” itself, I spent a great deal of time reading, not just the Bible, but Bible commentaries, historical and archaeological materials, and lots of apologetics, both liberal and fundamentalist. After all, I wanted to be certain I was not misremembering the strange superstitions taught to me as a child, and especially wanted to avoid attacking straw men. When I got around at last to the writing, most of the stories had been in my head for so long that they more or less wrote themselves.

What were some of the challenges and highpoints you faced writing this book?

I had to stop worrying about what my beloved fundamentalist extended family would think. This book would hurt some of them, and I was torn about that; but the issues were as important to me as to them, and I saw no good reason to continue being silent.

On another level, while most of the stories were very clear in my head, a few of them had technical problems that took a while to sort out. Most of these difficulties concerned selecting which of the many entrancing details of each extended narrative I should focus on. But the hardest story of all to start was the one that turned out to be the longest and darkest and arguably the most blasphemous: “Bridegroom of Blood in the Wilderness of Sin,” my unadmiring look at how Moses “freed” the Children of Israel. The difficulty was to find a workable point of view.

I tried Aaron, but he didn’t work for me, and anyway he died a little too early in the chain of events. I wrote several thousand words in third-person omniscient—a stilted disaster. I tried several other characters named in the Bible, including Phinehas, and I experimented with shuttling around among several first-person characters, both believers and skeptics, which just got messy. In the end, I chose to write as myself, a natural-born skeptic, in the head of one of Aaron’s unnamed daughters-in-law. Somehow the story took off after that, and became immensely satisfying to work on. That, incidentally, provided me with one of the high points of writing the book, the realization that I had at last found my way into the volume’s pivotal story.

Who is your intended audience?

Alas, most of the people who know the Bible well enough to catch the in-jokes are exactly the ones who won’t find them funny. So I suppose I wrote this book mostly for people who will dislike it, and won’t want to read it. Silly me. Fortunately, there are some atheists, agnostics, apostates and assorted infidels who may share my questions and appreciate the jokes; and I was also writing for, say, liberal theists who might be interested and stimulated by the refractedness of the vision, and readers with a general interest in religion as a social and historical phenomenon.

What books and authors inspired or influenced you in writing this book?

Nobody inspired or influenced this book directly; but I’ve had a stimulating time over the last thirty-odd years, reading such writers as Bertrand Russell, Kurt Vonnegut, James Randi, Richard Dawkins, Carl Sagan, Michael Shermer, Martin Gardner, Christopher Hitchens, and the marvelously lateral Marvin Harris.

I also did a great deal of reading around biblical topics, on both sides of the spiritual divide: for example, Donald Harman Akenson, Morton Smith, Tim Callahan, Karen Armstrong, Richard Elliot Friedman, Elaine Pagels, and—to remind myself forcefully of the fundamentalist position—Gleason Archer and Josh McDowell. Bart Ehrman’s intriguing books came in handy for the last rewrite.

What books and authors inspired or influenced you as a writer?

I am primarily a storyteller, with a great fondness for vivid, traditional, straightforward narrative, and not much patience for self-indulgent navel-gazing postnarrative forms. In my own voice, I can hear faint, odd echoes of many old favorites: Sinclair Lewis (Elmer Gantry); H.G. Wells (The History of Mr. Polly); Booth Tarkington (Alice Adams); J.B. Priestley (Angel Pavement); E.F. Benson (the Lucia novels); George Orwell (Keep the Aspidistra Flying); Dorothy Parker (the whole lot); and Jane Austen (ditto, in spades).

I am primarily a storyteller, with a great fondness for vivid, traditional, straightforward narrative, and not much patience for self-indulgent navel-gazing postnarrative forms. In my own voice, I can hear faint, odd echoes of many old favorites: Sinclair Lewis (Elmer Gantry); H.G. Wells (The History of Mr. Polly); Booth Tarkington (Alice Adams); J.B. Priestley (Angel Pavement); E.F. Benson (the Lucia novels); George Orwell (Keep the Aspidistra Flying); Dorothy Parker (the whole lot); and Jane Austen (ditto, in spades).

But perhaps the most direct influence—and the only writer whose general advice to younger writers resonated with me—was Kurt Vonnegut, to whose memory Lateral Truth is dedicated. Here, among many other sensible things, is what he said, in an essay in Palm Sunday: “The writing style which is most natural for you is bound to echo speech you heard when a child.” This, for me, was a kind of speech strong with the cadences of the King James Bible, and the British precision of my granny and her Canadian-born daughters; and it is sometimes their voices I hear in my head when I read over something I’ve written. This is not as scary as it might sound.

Discuss how and why you have re-visioned biblical stories here.

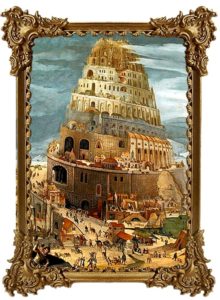

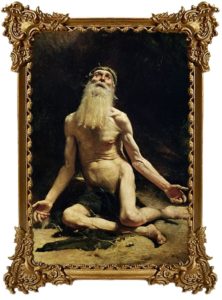

Lateral in the title says a lot. Many of the motifs are entrenched in Western culture, but only from a certain angle (usually the most flattering), and through a cheesecloth of reverence: Moses, for example, is entrenched as a great liberator, Bethesda as a symbol of healing, Job as a metaphor for patience. I look at these stories sideways, minus the cheesecloth. What I see is not always pretty.

I must say, though, some of the stories did not need a sideways look—full frontal was horrifying enough. For example, the vicious events in The Gibeah Wives are told pretty much straight as they come in the book of Judges, but I found a fair sampling of cover-to-cover literalists whom the story took by surprise. I know for dead certain it was not one of those we covered in Sunday school.

Why do you believe satire is important?

I’m reminded of Somerset Maughm’s story, “Jane”, where the title character is considered to be a priceless wit because she simply and directly tells the truth. Few of the stories in The Lateral Truth were explicitly intended to be satirical—rather, I meant to take iconic or striking scenes from the Bible, and follow them through to their logical human consequences. The fact is, some of those consequences were ludicrous enough to give the appearance of mockery or “holding up to scorn,” as in the dictionary definition of satire.

Your characters reveal challenges that many can relate to—for example, the trials and tribulations of labour. Can you discuss how and why you came to depict these and other issues? Discuss how and why they resonate and are relevant today.

Folks is folks, world without end. Trust me, I’m an archaeologist. We’ve always needed food, water, warmth, sex, companionship, esteem, security, a bit of a laugh, and something to keep our brains busy. Generally, we’ve also always wanted our kids to grow up safe, and our teeth not to hurt. Those issues are always going to be relevant, even to those of us who live in a cocooned, medicated, and well-fed bit of the world, where dentists abound, and no longer use the Black and Decker toolkits of my childhood.

The mention of labour is very interesting. Thinking about it, I see I’ve got a surprising number of childbirth references in The Lateral Truth, which was not exactly intentional. But you can hardly get more resonant and universal, not to mention primal, than childbirth. After my first child was born, I remember walking down the street thinking with wonder that every person I saw represented some woman going through a version of what I had just gone through. That blew my mind. (Though, for the record, my own experiences in that line were rapid and relatively painless.)

You have a wonderful ear for dialect and the phrases and expressions your characters use evoke oral stories and the oral storyteller. What advice would you give aspiring writers about writing dialogue and using dialect?

Again, I would invoke Vonnegut’s commonsense advice to use the natural rhythms of the language you first heard as a child. In my case, conveniently, I grew up with the grand, rolling rhythms of the King James Version, which were just what I needed for these stories. Also, it is pretty clear that the stories in both Testaments are rooted in oral tradition—a tradition that continues to be oral, because that is how I and millions of others first heard those stories, clustered around the knee of a story-telling Sunday-school teacher.

A curious note: in common with many other apostate children of religious families, I love the King James Version, and abhor the more recent dull and ugly translations, with their grisly efforts at modernity and relevance. This is one issue on which I can agree with my late Uncle Mark, a fundamentalist minister who resigned from the board of Bob Jones University over their use of versions other than the “divinely inspired” KJV.

As for dialogue advice to aspiring writers, two simple things. The first is to eavesdrop shamelessly, listening like a writer, and keeping a notebook handy. The second is to make a habit of reading your ms to yourself at reasonably frequent intervals, out loud. If you’ve been listening hard enough, hearing your own material out loud gives you a good indication of where problems might lie.

You have created strong female characters. Can you elaborate on how and why this is important (for you, for your writing)?

You have created strong female characters. Can you elaborate on how and why this is important (for you, for your writing)?

My agenda in The Lateral Truth is humanist, rather than feminist, though I see humanism as embracing fairness and respect for all genders. People are individuals, some of whom are strong and some weak, regardless of their gender identification. The same goes for my characters, so inevitably some of them are strong women.

I will add that there have been many strong women in my life—friends, sisters, aunts, daughter, mother, mother-in-law, cousins. This includes, of course, the many female fundamentalists to whom I am related, who are theoretically in subjection to their husbands, but are nonetheless powerful and assertive human beings. Lord, yes.

You challenge stereotypes here. How can writers unsettle stereotypes without perpetuating them?

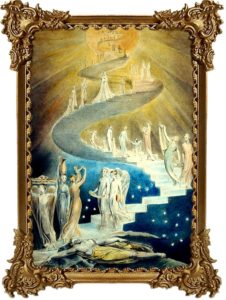

Stereotypes are, almost by definition, two-dimensional. You can play with them by adding a third dimension, either by using them as POV characters (eg, Adam, Martha), or by seeing them and their actions through the eyes of other characters (eg, Samson, Moses). Also, you can often look past the default stereotype to find an entirely different archetype—Moses as Dark Messiah, Jacob as Trickster, Job’s wife as the bereaved mother in myriad piétas.

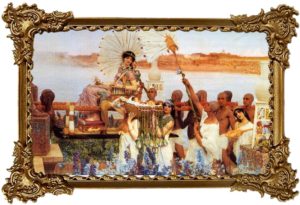

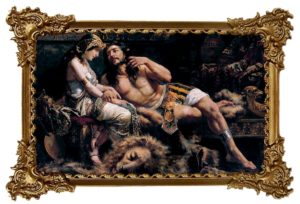

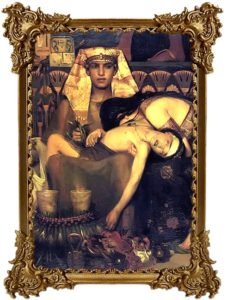

Some of the stereotypes I challenge in The Lateral Truth are the default images of certain biblical characters. Samson the action hero, for example: a positive metaphor in every respect but his weakness for loose women. The message is that holy violence is admirable, but women are bad, a snare that good ol’ boys would do well to avoid. In my version, seen through the eyes of his cousin, he is a psychopathic fathead responsible for his own stupid downfall. The story’s subtext, further, is that the original stereotype may be usefully manipulated for cynical ends (by the Levite, in this case), but its usefulness does not make it true.

Martha, by contrast, is commonly seen as a negative stereotype: the houseproud fussbudget, out of touch with her spiritual side. Mary, who drops everything to listen to the Master, gets a pat on the head in the consensus version. For me, however, Martha is simply being responsible and caring, and she deserves a better press. And, though the biblical account does not really give the end of the story, I challenge the stereotype by extrapolating to the chaos that would follow if everybody behaved like Mary.

Why is it important to create sympathy for your evil characters?

That rather begs the question. There were a few evil characters for whom I did not want to create sympathy: Moses, for example, who gets an entirely undeserved good deal in most other literary treatments I’ve ever seen, though he comes across in the Bible as a kind of Bronze-Age Jim Jones. Hitler, Torquemada, and the warring deities in “Dagon” also have no redeeming qualities. The prophet described in “The Last Breakfast” is an archetypal huckster. Etc.

On the other hand, the genocidal slaughterers featured in “The Gibeah Wives” should be sympathetic characters. They are a demonstration of the truth that ordinary people—good people—will do monstrous things if persuaded that some god or other wants them to. (I make no distinction here between religious and political dogmas: Mao, Hitler and Stalin were brothers under the skin to Moses, Jesus and Mohammed.) The mass murderers in “The Gibeah Wives” are sympathetic precisely because they do what ordinary humans habitually do: permit their rational and empathetic natures to be subverted by magical thinking and malign authority.

Protagonists also need to have flaws, to be human. Can you give some  examples from your book to illustrate this?

examples from your book to illustrate this?

Well, the most common flaws among the good guys in The Lateral Truth are either naïve optimism, cowardice, or cynical resignation. Adam is a nice enough guy, with great hopes for the future, but he’s a sucker of positively biblical proportions. Job’s wife, irremediably damaged, refuses to love. The nameless narrator of “Bridegroom of Blood” keeps silent in the face of evil; her husband Eleazar embraces the tyranny and becomes part of it. And so on.

You have many humorous scenes. How and why is humor effective in fiction?

One of my many rejection slips for this volume complained that the stories weren’t funny enough to keep people reading—as if blasphemy is only permissible when it adds “hey, just kidding.” Nuts to that. Some of the stories were not meant to be funny.

But yes, I did incorporate a lot of jokes in some cases, for a number of good reasons. Jokes can take readers by surprise, and jolt them into a lateral view. Jokes are insidious; they can be as viciously sharp as outright abuse, but more subtly. Most of all, jokes can break up the po-faced reverence with which religious motifs are usually approached. That is a good thing, especially as I strongly suspect some of the ancient texts were intended to be funny in the first place.

On a more personal note:

When did you first start writing fiction?

Apparently, I told great stories when I was a child. I don’t remember that. The first writing I remember was a poem about Takakkaw Falls in Yoho National Park, written on a paper towel when I was eleven. We were on holiday in a trailer, and a paper towel was the only writing material my mum could find. I wrote lots of really bad poetry in my teens, along with a few attempts at short stories. Going to university stopped me dead in my tracks for a few years as far as writing goes, but I always thought my time would come. It came when I was 31, as displacement activity while I was finishing my PhD thesis and having a baby. The irony of it! Nowadays I yearn for displacement activity to delay getting down to writing.

How long did it take you to write this book?

The first story was written in Hong Kong in about 1993, and four more followed at long intervals over the next few years, along with copious notes for others. In 2001, a grant from the Alberta Foundation for the Arts allowed me to get nine more down on paper in one hugely enjoyable burst of energy; but the last story written, “Death of a Pagan,” was not finished until late 2004. Then there were two major slice’n’dice revisions, one in 2005 after the Julian story was finished, and another in 2006/2007, to get the volume ready for press. Altogether, that comes to eleven years for the writing, and another three for polishing the manuscript and finding a publisher. And now, another seven years or so to bring up the 2nd edition.

What was the most difficult story to write and why?

Without question, “Bridegroom of Blood in the Wilderness of Sin,” the novella about Moses and the Children of Israel. I described, above, the problems I had finding a workable POV; but it was also a pain in the neck because the narrative covers four long, complex books of the Old Testament, all of which screamed to be included. Lots of nifty stuff had to be left out, alas, or I’d still be writing the damned story. I also did not want “Bridegroom” to turn into one of those fatuous exercises in giving naturalistic explanations for the Ten Plagues, or the Crossing of the Red Sea, or the Manna in the Wilderness. I have, however, been toying with the idea of using the novella as a springboard to a full novel treatment.

What advice would you give writers just starting out?

Read a lot, write a lot, and be prepared to slog through hard times. Oh, and good luck.