Why “Believe the Victims” is a Really Bad Idea.

Part Three: “Believe the Victims” can be wrong: false memory

We are not cameras. Memories are not cached in our brains in fixed form, like jpg files. They are both fluid and organic. They can be shaped and reshaped, confused, confabulated, even fabricated, by ourselves or others. We may photoshop or airbrush our own pasts by the very act of recall. And there is robust research showing that we cannot tell the difference—that false or confabulated memories will feel every bit as real the verifiable sort, and be held with equal or even greater confidence.

We are not cameras. Memories are not cached in our brains in fixed form, like jpg files. They are both fluid and organic. They can be shaped and reshaped, confused, confabulated, even fabricated, by ourselves or others. We may photoshop or airbrush our own pasts by the very act of recall. And there is robust research showing that we cannot tell the difference—that false or confabulated memories will feel every bit as real the verifiable sort, and be held with equal or even greater confidence.

Normally, this does not matter—our memories are close enough for government work, and shared with or validated by those around us. Where their accuracy does matter very much, however, is when they collide with the legal system, particularly in cases where the only evidence comes from the testimony of witnesses—or accusers. This is a lesson we should have learned at least a generation ago.

Thirty years ago, vast, shadowy networks of Satan worshippers all over the western world engaged in horrific acts of sexual abuse, blood sacrifice, torture, infant cannibalism, and murder. Except they didn’t. The Satanic Ritual Abuse epidemic was a moral panic, ultimately founded on interviews with children prejudged to be victims, and on the “recovered memories” of young women undergoing certain kinds of therapy. Overlapping with this was a spate of incest accusations and alien abduction narratives, again based on “recovered memories” but not involving Satanic rituals. In the 1990s, as the moral panic began to unravel, it emerged that the children’s increasingly bizarre narratives had been artifacts of the interview process, and that the young women’s “recovered memories” had been fabricated and implanted by the therapy itself. Valuable insights into the malleability of memory came out of this uproar, but lives and families were ruined along the way, many innocent men and women spent years in prison, and many women were damaged by the therapy that was supposed to help them. Altogether, it was a societal clusterfuck of monumental proportions.

Thirty years ago, vast, shadowy networks of Satan worshippers all over the western world engaged in horrific acts of sexual abuse, blood sacrifice, torture, infant cannibalism, and murder. Except they didn’t. The Satanic Ritual Abuse epidemic was a moral panic, ultimately founded on interviews with children prejudged to be victims, and on the “recovered memories” of young women undergoing certain kinds of therapy. Overlapping with this was a spate of incest accusations and alien abduction narratives, again based on “recovered memories” but not involving Satanic rituals. In the 1990s, as the moral panic began to unravel, it emerged that the children’s increasingly bizarre narratives had been artifacts of the interview process, and that the young women’s “recovered memories” had been fabricated and implanted by the therapy itself. Valuable insights into the malleability of memory came out of this uproar, but lives and families were ruined along the way, many innocent men and women spent years in prison, and many women were damaged by the therapy that was supposed to help them. Altogether, it was a societal clusterfuck of monumental proportions.

But so soon we forget. Especially where historical accusations are involved (i.e., allegations of crimes several years in the past), red flags for false or confabulated memories should now be among the first things we check for. But the kneejerk reflex to “believe the victim” suggests either an astonishing cultural amnesia about the lessons of the 1990s, or that the lessons were not widely taken in to begin with.

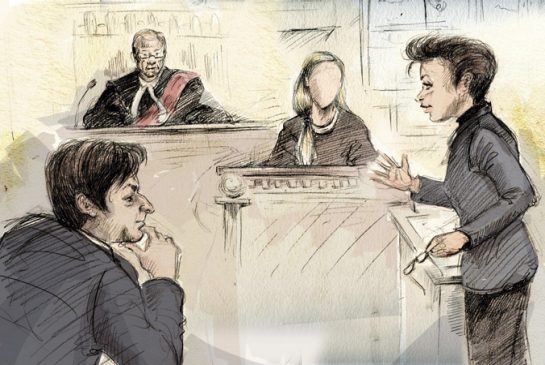

All of which brings us back to the trial of Jian Ghomeshi on historical accusations of sexual assault. Three women took the stand to accuse Mr. Ghomeshi of violent sexual assault between early December 2002 and early August 2003—accusations made only after Ghomeshi’s disgrace and downfall in October 2014, over a decade later, in the whirl of a wild media storm. Mr. Ghomeshi was found not guilty because the women’s testimony was unreliable enough to raise a reasonable doubt in the presiding judge’s mind; his summation points out numerous significant omissions, inconsistencies, and lies. But obvious red flags for false memory are present as well.

- Evolving Memories

The first witness’s original statement was somewhat confused, and kept changing in its details as she told and retold the story, first in media interviews, and then to the police. By her own account, she was unsure of the sequence of events at first; she also described herself as just “throwing thoughts” at the investigators. The intuitive implication is that the more she thought about it, the more she remembered. In fact, the reverse is far more probable.

Under pressure to produce a coherent narrative from fragmentary memories, we are prone to construct one that seamlessly combines genuine content with content from suggestions, imaginings, and wishful thinking—and we will forget which is which. In short, we will confabulate. The narrative so constructed will feel absolutely real and vivid. In this case, the timeline of the first witness’s developing narrative looks like a textbook case of confabulation in progress, but the most unambiguous giveaway is the detail of the Yellow Volkswagen Beetle. From the judge’s summation:

L.R. had a clear and very specific recollection of his [Ghomeshi’s] car being a bright yellow Volkswagen Beetle. It struck her as being a “Disney car”, a “Love Bug”. She said she was impressed that he was not driving a Hummer or some such vehicle. The “Love Bug” car was significant to her because it contributed to her impression of his softness, his kindness and generally, that it was safe to be with him.

Unfortunately for her narrative, this memory—however clear and specific—was demonstrably false; Mr. Ghomeshi did not buy the bug until seven months after the alleged assault. The judge does identify this as a false memory, going on to say:

In a case which turns entirely on the reliability of the evidence of the complainant, this otherwise, perhaps, innocuous error takes on greater significance. This was a central feature of her assessment of Mr. Ghomeshi as a “nice guy” and a safe date. Her description of his car was an important feature of her recollection of the first date. And yet we know that this memory is simply wrong. The impossibility of this memory makes one seriously question, what else might be honestly remembered by her and yet actually be equally wrong? This demonstrably false memory weighs in the balance against the general reliability of L.R.’s evidence as a whole.

The testimony of the second accuser (Lucy DeCoutere) evolved similarly as she told and retold her story in sworn statements to police and numerous media interviews: from “all jumbled” at first, to absolutely definite by the time the trial rolled around, and buttressed by vivid little narrative details—what Ghomeshi ordered for dinner, how he organized his shirts. The third accuser claimed that “some of the imprecision in her initial account to the police was due to her still ‘trying to figure it out.’” As noted above, “figuring it out” under pressure to recall is a high road to confabulating false memories.

The testimony of the second accuser (Lucy DeCoutere) evolved similarly as she told and retold her story in sworn statements to police and numerous media interviews: from “all jumbled” at first, to absolutely definite by the time the trial rolled around, and buttressed by vivid little narrative details—what Ghomeshi ordered for dinner, how he organized his shirts. The third accuser claimed that “some of the imprecision in her initial account to the police was due to her still ‘trying to figure it out.’” As noted above, “figuring it out” under pressure to recall is a high road to confabulating false memories.

A confabulated narrative, however, can be as notable for what it omits as what it includes. This brings us to:

- Post-Assault Contacts

All three accusers testified they had little or no contact with Mr. Ghomeshi after the alleged assaults, and no desire to continue a relationship with him. In all three cases, this turned out to be untrue. Suggestive emails and photos, a love letter, flowers, cuddles, a hand job, were not mentioned to the investigators or crown counsel until the defence revealed them at the trial.

The judge saw this as deceptive on the women’s part, though BTV proponents and the women themselves brought forward some heated rationalizations. Abused women, they said, will often stay with their abusers, or make excuses for them. The judge, they said, should not be basing his opinion on rape-culture stereotypes of how abused women are expected to behave. Two points here: first, the judge’s ruling was not based on how the accusers behaved after the alleged assaults, but on how they misreported their own behaviour. Second, it looks to me like the BTV advocates were equally using stereotypes of how victims should behave after an assault—they were just different stereotypes. And I think it is possible those stereotypes may have played a role in how the accusers’ narratives evolved.

For instance, Ms. DeCoutere, in explaining why she did not tell investigators about further flirtatious contacts with Ghomeshi, including a damning love letter written after the alleged assault, claimed she was “making an effort at ‘flattening the negative’ or normalizing a relationship.” Maybe so—but it is equally possible she incorporated into her historical narrative concepts that were absorbed during her well-publicized sideline as a heroine of victims’ advocacy.

The first witness (who has recently outed herself) claimed sexy photos and emails sent months later were an attempt to “bait” Mr. Ghomeshi into explaining his violent assault. More recently, she claimed to have only vague memories of the emails, and no memory of sending them. It seems her narrative is still evolving. [Note: if Mr. Ghomeshi had been the one to send suggestive emails with a hidden agenda after months of silence, it would almost certainly have been described as creepy stalking behaviour, and sexual harassment.]

The first witness (who has recently outed herself) claimed sexy photos and emails sent months later were an attempt to “bait” Mr. Ghomeshi into explaining his violent assault. More recently, she claimed to have only vague memories of the emails, and no memory of sending them. It seems her narrative is still evolving. [Note: if Mr. Ghomeshi had been the one to send suggestive emails with a hidden agenda after months of silence, it would almost certainly have been described as creepy stalking behaviour, and sexual harassment.]

Discussion

Robust research shows that past emotions can be “subject to forgetting and bias over time as people’s goals and appraisals of past emotional events change”. That is, how we remember feeling at the time of some event may be strongly affected by subsequent changes in attitude and emotion. In this case, the women claimed their hostility to and fear of Mr. Ghomeshi stemmed from the assault; the evidence dramatically shows otherwise.

When we confabulate, we try to make ourselves look better—to ourselves. We rearrange details and events, exaggerate or minimize our own roles, project current feelings into the past. We also conveniently forget or minimize things that do not fit the emerging narrative. That redacted version of the past becomes the truth for us, but it remains objectively untrue. And it is certainly not enough of a truth to send a man to jail.

In this case, BTV advocates—and the accusers—were incensed by the judge seeming to put so much weight on petty inconsistencies. What did it matter whether L.R. was wearing hair extensions? What did it matter what car Mr. Ghomeshi drove? Who cares exactly how many blows were landed, and in what order? Such questions miss the point. The women swore to certain narratives; inconvenient facts falsified those narratives in nontrivial ways that reflect some lies by omission, some fudging of the truth, and notably some false memories. They were clearly not giving a true account—but it is perfectly possible they felt they were.

But which part was confabulated? For the record, I have little doubt that Mr. Ghomeshi committed an act of violence on each of the three accusers—but beyond that, there is a lot of scope for the formation of false memories. Consider an aIternate scenario: that Mr. Ghomeshi was effectively “auditioning” each of these women for the role of BDSM playmate; that he sounded them out beforehand about “rough sex,” and imagined he had a form of consent; that he lost interest and dumped them when they failed to get excited about being slugged; and that they were hurt and humiliated by his rejection. All this is speculation, but it fits more of the facts than the sworn testimony did. And if it happened to me, I would certainly want to soothe my self-esteem by editing my memories and casting myself as a victim—and you would be wrong to believe me.

Next: “Believe the victim” does more harm than good.

Previous posts in series: