Why “Believe the Victims” is a Really Bad Idea.

Why “Believe the Victims” is a Really Bad Idea.

Part Two: “Believe the Victims” can be wrong: false testimony.

Contrary to politically correct belief, it sometimes happens that people making accusations of sexual assault are not telling the truth—though this is a more complicated issue than the infamous “bitchz be lyin” trope. In the Ghomeshi case, the lack of truthfulness did include some outright lies by both omission and commission, but also—critically—some important issues to do with memory. False testimony and false memory are separate issues, and I have not seen the latter discussed in connection with Ghomeshi’s accusers; and yet, the red flags are there.

But, first—the general issue of bearing false witness. Implicit in the mantra “believe the victims” (BTV) is the assumption that women do not lie about sexual assault—that false accusations are vanishingly rare, and can therefore be pretty much discounted. Also implicit is the attitude that it does not matter if a few innocent guys get punished for assaults or rapes they did not commit.

As to how often false accusations are made, the rate (like the rate of unreported  assaults) is impossible to peg statistically for methodological reasons, partly to do with trying to separate out unfounded from unproven from entirely hypothetical unreported assaults. The definitions and criteria are iffy, inconsistent across jurisdictions, and may be differently interpreted according to one’s agenda. Take, for example, a case where no charges are brought because of a lack of evidence. BTV advocates may see it as an example of the system failing a victim, whereas others may classify it a false accusation; in fact, it should not really be entered in either of those columns. Which part of “lack of evidence” is difficult to understand?

assaults) is impossible to peg statistically for methodological reasons, partly to do with trying to separate out unfounded from unproven from entirely hypothetical unreported assaults. The definitions and criteria are iffy, inconsistent across jurisdictions, and may be differently interpreted according to one’s agenda. Take, for example, a case where no charges are brought because of a lack of evidence. BTV advocates may see it as an example of the system failing a victim, whereas others may classify it a false accusation; in fact, it should not really be entered in either of those columns. Which part of “lack of evidence” is difficult to understand?

But the fact that false accusations are made at all should hold us back from rushing to presume willy-nilly that an accusation is true. It is hard to see, for example, how BTV can be bandied about so uncritically in the face of unambiguous high-profile cases of fabricated accusations, some of them very recent—the Rolling Stone debacle, Mattress Girl, the Duke lacrosse team hoax, the tragic injustice done to Brian Banks. But these high-profile cases are only the tip of a disturbing iceberg, as documented, for example, by the Community of the Wrongly Accused, Families Advocating for Campus Equality, and the Innocence Project. The narratives and statistics these sources make available reveal how many different ways false accusations may be made, and the terrible effects they have on innocent men and their families.

Some are simply mistakes, cases of mistaken identity when a genuine assault has taken place. The accusers in such cases are indeed victims, but not victims of the accused. The effect on an accused innocent, however, will be just as dire. More than half of the exonerations effected by the Innocence Project have involved mistaken rape allegations, with the wrongfully convicted having spent years, even decades, in prison, until being cleared by DNA testing.

Some false accusations are deliberate, and the possible motives can be hugely diverse, including but not limited to revenge, mental illness, attention-seeking, and the old classics of avoiding blame or shame or the consequences of infidelity. More disturbing yet is the class of fabricated accusations made by “rape-culture” activists seeking to promote awareness of sexual assault—which is rather like shouting Fire in a crowded theatre to promote awareness of fire safety. For example:

- The rape counsellor and sophomore at George Washington University who disseminated a hoaxed story about a white woman being raped on campus by two black men with “particularly bad body odour;” according to her excuse when the story unravelled, it was to focus public attention on the problems of safety for women.

- The Take Back the Night hoax at Oberlin College, where activists publicly named and shamed an innocent male student, posting rape accusations around campus. One female student was quoted as saying: “So many women get their lives ruined by being assaulted and not saying anything. So if one guy gets his life ruined, maybe it balances out.”

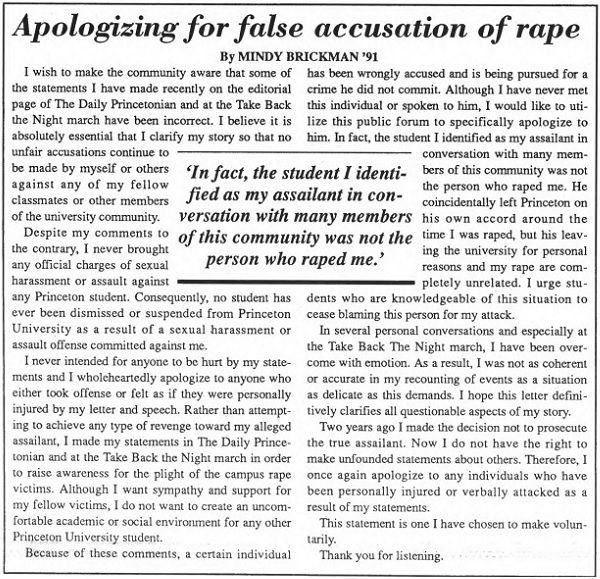

- The female law student at Princeton who repeatedly slandered a male student with rape accusations, including an emotional speech at a Take Back the Night rally—accusations which she subsequently retracted in an open letter (below) that claimed she was only trying to “raise awareness for the plight of campus rape victims.”

- The student who falsely accused a respected professor of serial rape because—ironically—she was incensed at classroom discussions of false rape accusations.

A knee-jerk cry of “Believe the Victims” is clearly a visceral rather than a rational response, and it can be bloody dangerous since it simultaneously sanctifies the accuser and demonizes the accused. A better response might be to take any accusation seriously enough for it to be investigated fairly and thoroughly, while (a) giving the accusers the support and respect they need, and (b) respecting the rights of the accused.

Next: the issue of false memory.