A few years back, a close relative of mine served on the defense team in a very high-profile serial-murder trial. When I mentioned this to friends and acquaintances at the time, they almost invariably looked disapproving and came out with some version of this: “Tell her not to work too hard.” I was reminded of that during this past week, when Jian Ghomeshi’s defence counsel was widely reviled for doing her job too well.

A few years back, a close relative of mine served on the defense team in a very high-profile serial-murder trial. When I mentioned this to friends and acquaintances at the time, they almost invariably looked disapproving and came out with some version of this: “Tell her not to work too hard.” I was reminded of that during this past week, when Jian Ghomeshi’s defence counsel was widely reviled for doing her job too well.

[Disclosure: I liked Jian Ghomeshi in the pre-scandal days, both as a slightly goofy Canpop singer in the band Moxy Früvous, and as a brilliant interviewer on CBC’s flagship radio show, Q. After the scandal, he was dead to me—not because he was eventually charged with sexual assault, but because I could not (and still cannot) get past his own admission that he gets his sexual jollies out of hurting his partners. To quote what I said last year: “You need court-proof evidence to send somebody to jail—you do not need it to conclude that he is an asshole.” I will confess to being both mystified and disgusted by BDSM. But that’s my problem.]

Anyway, we’ve now been shown some evidence. It was supposed to be this big, long trial, three weeks maybe, loads of witnesses, a celebrity defendant, an array of accusers, a watershed moment in Canada’s evolution in social justice. What we got instead was six days in court, three accusers who also comprised 75% of the witnesses, and the kind of shattering courtroom drama that can only arise from genuinely shocking revelations – shocking, that is, to the blindsided prosecutors and all those who thought this would be a slam-dunk for the crown. Yep, Jian Gomeshi’s trial for sexual assault was brief, but full of surprises, and the smart money is now on the defense.

For the benefit of anyone who is (a) not Canadian, or (b) Canadian, but spent the last week in a deep mineshaft with no cell reception, here is what happened. All three accusers presented basically the same story: in the middle of a flirty/romantic encounter—consensual kissing—Mr. Gomeshi abruptly and variously dealt out slaps, punches, hair-pulling, and choking for up to ten seconds…and then stopped. All denied they had given consent to BDSM activity; all denied that they pursued any subsequent relationship with Mr. Ghomeshi. And these events were alleged to have taken place in 2002 and 2003, more than a decade before the accusers came forward in the media blitz of 2014. Indeed, numerous other women made similar allegations at that time, but only these three cases (and one other, scheduled for later this year) were considered solid enough to be taken to court. Mr. Ghomeshi was charged with sexual assault rather than common assault, because the alleged violence took place in the context of consensual kissing. Thus, the baggage that now comes with accusations of sexual malfeasance began to pile up: believe the victim/rape culture/trigger warnings/war on women, etc.

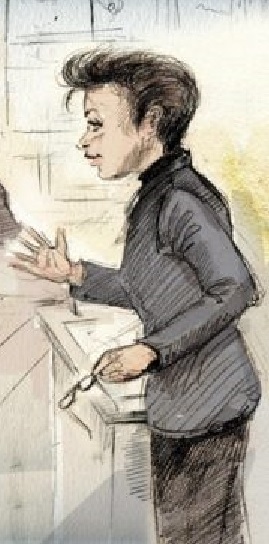

Actually, courtroom drama can be pretty dull. Not this time. Ghomeshi’s defence counsel, the brilliant Marie  Henein, insisted on doing the unthinkable in the service of her client: she did not believe the victims.

Henein, insisted on doing the unthinkable in the service of her client: she did not believe the victims.

Instead, she did her homework, compiling emails, photos, social media postings and other documentation that directly, plainly, and irredeemably contradicted the accusers’ narrative. Complainant #1, far from cutting off all contact with her tormentor as she claimed, went out with him on several further dates and, months later, sent him come-hither emails and a picture of herself in a string bikini. Complainant #2 barraged him with explicitly intimate emails and even a lengthy handwritten love letter in the days and months after the alleged assault. Complainant #3 took him home with her a few days later, for a hand job and a snuggle. Numerous other omissions, representations, inconsistencies, and apparent lies were also brought forward by Ms. Henein, in a sustained evisceration of the accusers’ claims and credibility. Final arguments were made on Thursday, and the matter was left in the lap of the judge, who will hand down his verdict next month.

Now, the press is unanimous on a few points: the swift, sure sword that is Ms. Marie Henein made bloody mincemeat of the crown’s case; Mr. Ghomeshi was wise to keep his mouth shut; Ms. Henein wears fabulous shoes. On all other issues, opinion is heavily polarized.

One side regards Ms. Henein as a gender traitor, a sell-out, a sister-punishing chill-girl complicit in the re-victimization of Mr. Gomeshi’s victims. The accusers’ post-traumatic actions are irrelevant, they say—after all, many abused women continue to cling to their abusers. Only the alleged abuse itself is relevant; to examine the womens’ actions is tantamount to victim-blaming. And as survivors of sexual assault, they deserve special consideration—anything else is rape culture/rape apology/misogyny in action.

Examples: Feminist firebrand Heather Mallick spins every possible rape-culture meme into a satirical search for the perfect sexual-assault complainant; not once, however, does she mention truthfulness, or making full disclosure to the officials who are supposed to be prosecuting one’s case. Another columnist makes a startling admission: “Henein’s apparent religious devotion to the law seems to supersede her feminism” – as if the two are by definition incompatible. Yet another trots out that famous Madeleine Albright quote with reference to Henein: “There’s a special place in Hell for women who don’t help other women.”

The other side of the debate regards Ms. Henein as a defence lawyer doing what a defence lawyer is supposed to do: defend. It (correctly) perceives that Ms. Henein’s dismantling of the accusers’ credibility was not based on their sexual behaviour, but on the fact that they were woefully, patently, economical with the truth. It questions the conflation of these accusers’ experiences with the trauma of long-term domestic violence—one of the many excuses given for their lies and omissions. It protests the trend towards treating sexual assault as a special category of offense, where accusers are absolved from normal inquiry into their claims (believe the victim!); it protests the corollary of that trend, that the accused must be presumed guilty.

Here is a central irony: the accusers in this case were kid-gloved by the police and the crown in exactly the way hard-line feminists demand the victims of sexual assault should be treated. Their narratives were believed. Their sensibilities were protected. The gaps and inconsistencies in their claims were papered over as typical of “how victims of trauma behave.” As perceived victims, they were held to be above reproach and above question; it is clear from the (illegal) communications among the accusers that they gleefully expected the trial to be a rubber stamp on Mr. Ghomeshi’s guilt. Ms. Henein did more than hit them with a harsh reality check—she did them the honour of treating them like adults, as opposed to special snowflakes. And she did all of us the favour of taking due legal process seriously.

I’ll finish as Ms Henein did, with a quote from Justice Claire L’Heureux-Dubé, a feminist and the first woman from Quebec in the Supreme Court of Canada:

One cannot over-emphasize the commitment of courts of justice to the ascertainment of the truth. The just determination of guilt or innocence is a fundamental underpinning of the administration of criminal justice. The ends of the criminal process would be defeated if trials were allowed to proceed on assumptions divorced from reality. If a careless disregard for the truth prevailed in the courtrooms, the public trust in the judicial function, the law and the administration of justice would disappear. Though the law of criminal evidence often excludes relevant evidence to preserve the integrity of the judicial process, it is difficult to accept that courts should ever willingly proceed on the basis of untrue facts.