Moral panics come in many different flavours. Some are fomented at the top levels of society, some at the grass-roots, and some in agenda-driven groups with plans to make the world a better place, in line with their special definitions of “better.” Some spring out of misinformation, or disinformation, or popular misconception, or popular mythology. What they all have in common is that (a) nothing terribly useful comes out of them, and (b) somebody gets hurt. For example:

Moral panics come in many different flavours. Some are fomented at the top levels of society, some at the grass-roots, and some in agenda-driven groups with plans to make the world a better place, in line with their special definitions of “better.” Some spring out of misinformation, or disinformation, or popular misconception, or popular mythology. What they all have in common is that (a) nothing terribly useful comes out of them, and (b) somebody gets hurt. For example:

Western Europe, eleventh century AD; the first millennium has drawn to a close, signs and portents are in the sky, and the long-promised End of the World is at hand. This is generally considered to be a good thing, since it means Christ will come back and set up a new and much nicer world, one without cold, hunger, crushing labour, death, corrupt clergy, psychotic aristocrats, and toothache. But first, the faithful of Christendom have to roll out a blood-red carpet for the returning Messiah. Christ will not sully his foot on Earth’s surface until all unbelievers have been either converted or swept away in a tide of carnage, and Solomon’s Temple has been rebuilt in Jerusalem. Enter the Crusades.

Now, the origins of the First Crusade are monstrously complex – byzantine, even – and I won’t even try to address them here. But legend credits a charismatic ascetic, Peter the Hermit, with the vision that set the ball rolling; disgusted at the maltreatment of Christian pilgrims by the Seljuk Turks holding Jerusalem and impelled by an actual interview with Christ, he is said to have persuaded the Byzantine emperor to write the fateful letter to Pope Urban, begging the help of Christendom against the murderous infidels. This was reinforced by a letter which Christ himself had put into the Hermit’s hands. The Pope, with Peter at his side, responded by calling for a crusade to liberate the Holy Land. That’s the legend.

even try to address them here. But legend credits a charismatic ascetic, Peter the Hermit, with the vision that set the ball rolling; disgusted at the maltreatment of Christian pilgrims by the Seljuk Turks holding Jerusalem and impelled by an actual interview with Christ, he is said to have persuaded the Byzantine emperor to write the fateful letter to Pope Urban, begging the help of Christendom against the murderous infidels. This was reinforced by a letter which Christ himself had put into the Hermit’s hands. The Pope, with Peter at his side, responded by calling for a crusade to liberate the Holy Land. That’s the legend.

In fact, the most reliable evidence shows only that Peter preached the crusade after the Pope’s call, the most successful of many grass-roots prophets who ranged the towns and countryside gathering hosts of wildly enthusiastic followers out of the poorer classes. The rewards they promised were compelling, both spiritual and temporal: guaranteed remission of sins, lots of plunder, real estate in the Holy Land, and the prospect of speeding Christ’s return. The result was disastrous: wave after wave of rabble armies pillaging their way across Eastern Europe, massacring or being massacred by their fellow Christians before they ever had a chance of grappling with the Saracens. This certainly made life more difficult for the baronial armies that followed them, who nonetheless actually made it to the Holy Land.

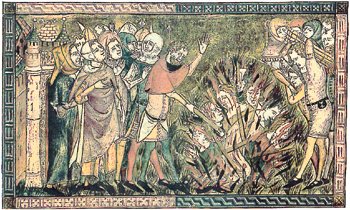

So far, what we see is less a moral panic than a moral rapture—a craze. But at least one aspect of this craze had distinct moral-panic overtones, and set the scene for some doozies later on. This concerns the fate of Jewish communities in France and Germany as the first waves of “pauper crusaders” were setting off, under prophets like Peter the Hermit. Up until that point, Jewry embedded in Christendom had not done too badly, and had not borne the crushing load of anti-Semitism found in later centuries. But the crusading fever that swept Western Europe was built on the demonization of non-Christian others, and the moral necessity of eliminating them. What better way to start a crusade than to eliminate the demons at home? Despite efforts by the clergy and local authorities to protect them, Jewish communities in the Rhineland and along the Danube were virtually extirpated by massacre or forced conversion before the pauper armies set off for the Holy Land.

And with Jewry thus firmly established as the demonic Other, the stage was set for a rolling series of later moral panics, with hideous results. These mainly took one of three forms, reflecting Christian myths and fears about the perceived social deviants in their midst, and how they threatened the social fabric.

1. The Blood Libel. The secret ingredient in Jewish holiday baking, according to this recurrent moral panic, was the blood of a Christian child, suitably tortured to death. This was widely believed in Europe from the 12th century on, despite the clear prohibition against human sacrifice in Jewish law, and the dietary restriction against using blood of any species – human or otherwise – in food preparation. The disappearance or murder of a Christian child was apt to be blamed on the nearest Jewish community, almost inevitably resulting in torture, looting, pogroms, and mob justice.

1. The Blood Libel. The secret ingredient in Jewish holiday baking, according to this recurrent moral panic, was the blood of a Christian child, suitably tortured to death. This was widely believed in Europe from the 12th century on, despite the clear prohibition against human sacrifice in Jewish law, and the dietary restriction against using blood of any species – human or otherwise – in food preparation. The disappearance or murder of a Christian child was apt to be blamed on the nearest Jewish community, almost inevitably resulting in torture, looting, pogroms, and mob justice.

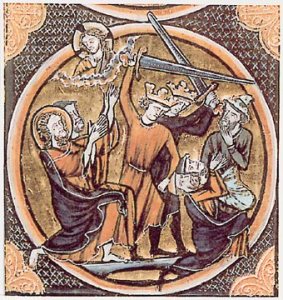

2. Desecration of the Host. By Catholic dogma, the host, or communion wafer, may look and taste like bread, but has been magically transformed into the actual flesh of Christ; thus, defiling a communion wafer is a shocking blasphemy. From the 13th century, Jews were accused of obtaining communion wafers for use in demonic rituals, where they would maliciously re-enact the torture and crucifixion of Christ. Though no evidence beyond the denunciation itself would be presented (and the denouncer usually had something to gain), the accusation would almost inevitably result in torture, looting, pogroms, and mob justice.

3. Well-Poisoning. In the 14th century, populations terrorized by the Black Death grasped at the theory that Jews were causing the plague by poisoning the wells, as part of a satanic plot to destroy Christendom. The results, as usual, were torture, looting, pogroms, and mob justice.

The sequence leading from the First Crusade to the anti-Semitism of the following centuries illustrates some general features of moral panics and how they grow. First, there is a threat to the social fabric, either real or imagined: the Muslim “persecution” of Christian pilgrims, the upcoming apocalypse, the danger to children, the plague, the imaginary Jewish plot.

Second, there are the agents of panic: the ”moral entrepreneurs,” who define the threat (or, in some cases, create it), and lay the blame on a certain set of social “deviants”. They also have the most to gain from a moral panic, in terms of pushing an agenda, accruing political capital, profiting in material terms, or enjoying personal power over a following. Here we have Peter the Hermit, his fellow prophets, and their successors in later moral panics, who focused public attention on the perceived threat from Muslim and Jewish “Others.”

Third, hyperbolic claims are made about the social “Others,” on little or no valid evidence, and presented in incendiary terms: gross exaggerations of the Others’ numbers and influence, of the depths of their evil, and of how much harm they can actually do, plus overblown accusations of immoral motives or actions.

Fourth, the claims are false, and are eventually shown to be groundless – too late for the victims, of course. But however absurd these claims are when viewed rationally, their residue may end up enshrined in the society’s stock of beliefs as a kind of “truth,” grafted onto the stereotype of the stigmatized group even after the moral panic has burned itself out. Thus, the demonization of the Jews in the First Crusade became the foundation for later outbursts, with even more tragic consequences in the long term.