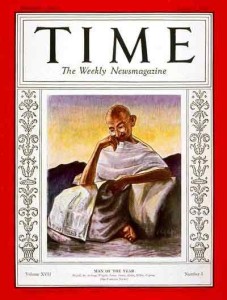

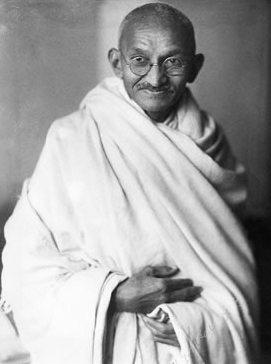

Mohandas K. Gandhi, known as Mahatma Gandhi, meaning “Great Soul,” is widely considered a saint and a martyr, the father of his nation, the prophet of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience; a man who set an example of ascetic self-sufficiency, including spinning his own yarn for weaving his own loincloths; a revolutionary who faced down the mighty British Raj and pressed for the rights of the poor, even the despised untouchables, whom he called the “children of God”. A mystic, peacemaker, prophet of minimalism, messiah of liberation—surely the antithesis of compatriots like the Baghwan Shree Rajneesh, with his fleet of Rolls Royces, or dark messiahs like Jim Jones, with his doctrine of revolutionary suicide, or Adolf Hitler, with his unifying myth of Aryan nationhood. In fact, questioning Gandhi’s saintliness feels a bit churlish, as heretical and apt to offend some people as questioning the divinity of Jesus would offend others. Yet, there are grounds to see Gandhi as fitting in with the same general messianic model as the antiheroes mentioned above.

Mohandas K. Gandhi, known as Mahatma Gandhi, meaning “Great Soul,” is widely considered a saint and a martyr, the father of his nation, the prophet of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience; a man who set an example of ascetic self-sufficiency, including spinning his own yarn for weaving his own loincloths; a revolutionary who faced down the mighty British Raj and pressed for the rights of the poor, even the despised untouchables, whom he called the “children of God”. A mystic, peacemaker, prophet of minimalism, messiah of liberation—surely the antithesis of compatriots like the Baghwan Shree Rajneesh, with his fleet of Rolls Royces, or dark messiahs like Jim Jones, with his doctrine of revolutionary suicide, or Adolf Hitler, with his unifying myth of Aryan nationhood. In fact, questioning Gandhi’s saintliness feels a bit churlish, as heretical and apt to offend some people as questioning the divinity of Jesus would offend others. Yet, there are grounds to see Gandhi as fitting in with the same general messianic model as the antiheroes mentioned above.

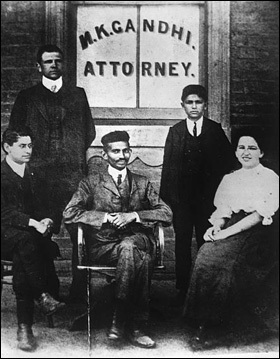

A merchant-caste Gujerati born in 1869, Mohandas Gandhi made an arranged marriage at the age of 13, and at the age of 19—already a father of two—travelled to England to study law. There, he came under the influence of the Theosophists, who turned him on to the ancient Sanskrit epics, especially the Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana, which informed his later aspirations for India. He was even introduced to Madame Blavatsky and her eventual successor Annie Besant, in 1889. It is a little ironic that this major figure in Eastern thought came to his own culture’s scriptures secondhand through a European conwoman’s cult.

According to legend—and the Oscar-winning 1982 movie—Gandhi was sensitized to racism when he went to South Africa for his  Indian law firm, and got kicked out of a first-class train carriage because of his colour. This sparked off nearly twenty years of campaigning for the civil rights of Indians in South Africa, during which he developed and honed his techniques of passive resistance and nonviolent protest, plus his dedication to communal living, at his Ruskin-inspired ashram outside Durban. Contrary to legend, he did not campaign against segregation, nor for the rights of black South Africans—in fact, he was all for segregation, provided Indians were on the nicer side of the dividing line. He was just not very keen on the “kaffirs”:

Indian law firm, and got kicked out of a first-class train carriage because of his colour. This sparked off nearly twenty years of campaigning for the civil rights of Indians in South Africa, during which he developed and honed his techniques of passive resistance and nonviolent protest, plus his dedication to communal living, at his Ruskin-inspired ashram outside Durban. Contrary to legend, he did not campaign against segregation, nor for the rights of black South Africans—in fact, he was all for segregation, provided Indians were on the nicer side of the dividing line. He was just not very keen on the “kaffirs”:

[1896] Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness. (Collected Works, Vol. 1: 410)

[1903] We believe as much in the purity of race as we think they do… We believe also that the white race of South Africa should be the predominating race. (Collected Works, Vol. 3:256)

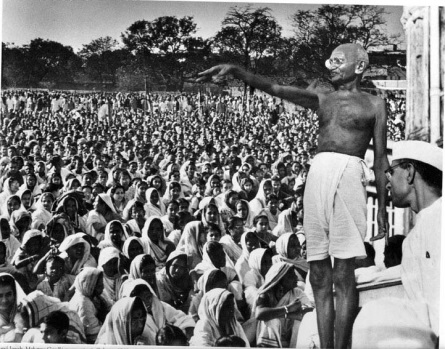

When Gandhi returned to India in 1915, he already had a reputation built on his activities in South Africa—not just as a potential politician, but as a holy man, a guru. Charismatic and ambitious, he rapidly became a major political figure, particularly as the messiah of the peasantry; and in 1921, he acquired executive authority in the National Congress. For the next twenty-seven years, he dominated the messy and volatile Indian political scene, in and out of Congress and jail, sometimes as the immoveable object, sometimes the irresistible force. In solidarity with poor Indians, and in accord with his principle of simple living, he adopted indigenous dress in 1915, and simplified it to the familiar loincloth and shawl in 1921.

In character, he was definitely charismatic, and apparently witty, clever, and lovable, though not always so to his wife and sons. Gaining a huge following, he swept along scores of millions with him in his crusade for swaraj, or self-rule, freedom from both the Brits and from the negative circumstances of one’s own life. In due course, he was worshipped—like a god, or maybe a rock star—and was even said to have performed miracles. To his credit, he debunked these supposed miracles whenever he could, claiming to be irritated by his personality cult, though he did admit to enjoying the adulation of the crowds. He was just a simple man, he said, living humbly in an ashram, on fruit and goat’s milk; but this humble man could sway millions, could turn violent mobs on or off as if with a light switch, and more than once bent both the Brits and his fellow Indian politicians to his will simply by threatening to fast until he died. [Note: Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin, suggested wryly that Gandhi never tried this technique with the Muslims because they might well have called his bluff.]

So: a man with remarkable charisma and political will, and one who has been informally canonized in the west, as the saint of nonviolent protest and the father of modern India. That is the narrative line taken by Attenborough’s Oscar-winning movie, but of course the story is not that simple. For one thing, Gandhi was happy to tolerate violence when it suited his political agenda, and kept having to call off nonviolent protest campaigns because the violence got out of hand. And while India did become independent on his watch, serious historians (both Indian and European) point out that he was virtually irrelevant at the end, and had held back the process of independence for years through his intransigence over the question of power-sharing with the Muslims. Britain had been wanting to “quit India” for some time, and at any rate could not have held onto the subcontinent after the weakening effects of the Second World War. One of the factors holding them in India before the war was a perfectly justified fear of civil war breaking out as soon as they left, because the interested parties (including Gandhi) could not compromise on the terms of independence. But Gandhi’s own vision for India needs a closer look.

So: a man with remarkable charisma and political will, and one who has been informally canonized in the west, as the saint of nonviolent protest and the father of modern India. That is the narrative line taken by Attenborough’s Oscar-winning movie, but of course the story is not that simple. For one thing, Gandhi was happy to tolerate violence when it suited his political agenda, and kept having to call off nonviolent protest campaigns because the violence got out of hand. And while India did become independent on his watch, serious historians (both Indian and European) point out that he was virtually irrelevant at the end, and had held back the process of independence for years through his intransigence over the question of power-sharing with the Muslims. Britain had been wanting to “quit India” for some time, and at any rate could not have held onto the subcontinent after the weakening effects of the Second World War. One of the factors holding them in India before the war was a perfectly justified fear of civil war breaking out as soon as they left, because the interested parties (including Gandhi) could not compromise on the terms of independence. But Gandhi’s own vision for India needs a closer look.

Independence from Britain was only part of the package. Gandhi had a solid millenarian agenda: the return of a long-past, pre-colonial Golden Age—and incidentally, a mythical one. The Brits would be gone. Past glories would be revived, in their pure, original form. This was, in fact, a classic revitalization scenario, along the same lines as the Ghost Dance or the Xhosa cattle killings.

In this revitalized context, the future that Gandhi envisioned for India was one of countless little self-sufficient village economies dotting the countryside, mini-republics peopled with enlightened farmers who would presumably weave their own loincloths. They would eschew Western medicine, science and education. There would be no foreign trade, since the villages would sustain themselves; no need for government, since the villages would rule themselves. There would be no exploitation or exclusion of untouchables or people of other faiths, since all were the creatures of God. And so forth.

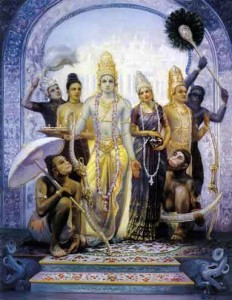

This vision was called “Rama Rajya” – or the rule of Rama—a symbolic return to that mythical golden age of plenty and prosperity when the God-King Rama presided over the happy primeval Hindus, whole eons before the Muslims and the Brits arrived to mess things up. Indeed, Gandhi thought of Muslim and Christian Indians as being lapsed Hindus, ancestrally converted by their various conquerors, but Hindu at the core. India would thus be both freed and unified by the great national narratives of Sanskrit literature, and by a single great national symbol, Rama himself.

when the God-King Rama presided over the happy primeval Hindus, whole eons before the Muslims and the Brits arrived to mess things up. Indeed, Gandhi thought of Muslim and Christian Indians as being lapsed Hindus, ancestrally converted by their various conquerors, but Hindu at the core. India would thus be both freed and unified by the great national narratives of Sanskrit literature, and by a single great national symbol, Rama himself.

And they would achieve all this nonviolently, because purity of heart and commitment to the principles of satyagraha (truth-force) and ahimsa (nonviolence), aka turning the other cheek, were the greatest weapons of all under God: in fact, a magical way of gaining power over one’s enemies. Those who see Gandhi’s principle of nonviolent protest simply as a moral statement are overlooking that magical, mystical aspect.

Anyway, Rama Rajya sounds rather charming, but—could it have worked? Not likely. Even leaving aside myriad competing ethnic/religious interests, a return to a simple agrarian economy is not feasible once a society reaches a certain level of complexity, at least not without a horrific downsizing. The only serious attempt to move a whole society back to instant agrarian simplicity was the hideous experiment in social engineering carried out by Pol Pot in Cambodia in the 1970s, and we all know how well that went.

But even without the practical problems involved in Rama Rajya, there were fatal flaws in Gandhi’s dreamworld. Revitalization, though seductively appealing to many Hindus, did not appeal to a good many others—for example, the politicians doing their best to work out reasonable compromises in a messy multiethnic situation, and to frame them in a secular postcolonial system. Even to those who loved Gandhi, like Nehru, Gandhi was a loose cannon. His insistence on a certain northern-based version of Hinduism alienated sections of South India, for whom Rama was anything but a symbol of liberation. Gandhi’s mystical vision of the future, they recognized as nonviable.

Worse was his way of dealing with the Muslims—a sizeable minority in the subcontinent overall, and a majority in many areas. The Muslims, worried about what would happen when the Brits left, had long campaigned for concessions, safeguards, and guaranteed seats in the government of a free and unified India. They were especially upset by Gandhi’s Hinducentric mystical revitalization, however much Gandhi dressed it up as “universalism”. Partition into separate Muslim and Hindu nations was talked of as early as the 1920s, but Gandhi rejected it utterly; the Muslims, he said, must remain “the prisoners of our love.” At the same time, many Hindus were outraged by what they saw as Gandhi’s appeasement of the Muslims at the expense of Hindu interests, which is what eventually got him killed. Gandhi’s policy of trying to woo the Muslims into a union that was based on Hindu mysticism was virtually guaranteed to split Indian communities along the religious faultlines.

Another group that was not enchanted with Gandhi’s vision was, oddly enough, the very “untouchables” for whose improved conditions he worked so tirelessly. The untouchables, or dalits, comprised about 15% of the population, and their traditional position was ghastly. The Hindu system was and is caste-based, a hereditary hierarchy entrenched in the very scriptures that Gandhi was promoting. According to Hindu beliefs, dalits were born as dalits because of atrocious sins committed in previous lives. Therefore, they were atrociously discriminated against, condemned to the lowest occupations—latrine cleaning, for example—barred from entering temples, and liable to violent retribution if they got too uppity—say, by putting on shoes. Even the touch of a dalit’s shadow was considered polluting to a caste Hindu.

Gandhi, who had done wonders pushing for dalit rights to education and self-improvement, wanted to abolish that caste-consciousness, and bring the dalits into the Hindu mainstream—as if he could make it so, simply by willing it. But caste consciousness is integral to the Hindu religious worldview—some even see Hinduism as a routinized religious system set up solely to protect the privileges of the higher castes. There was much negative reaction from caste Hindus—but even more from the dalits themselves. Why?

The dalits wanted self-determination, and an end to centuries of being treated as subhumans. Under such home-grown leaders as Bhimrao Ambedkar, they were working to be treated as a separate ethnic/religious group, looking for the same kind of deal as the Muslims, with power to elect a guaranteed number of dalit representatives. Many did not want to be Hindu at all, since Hinduism institutionalized their oppression, and they converted to Islam, Christianity or Buddhism. They did not trust the caste Hindus to treat them decently, just because Gandhi said it should happen. And their mistrust was justified—even now, especially in rural India, the dalits are still subject to violent discrimination.

Gandhi brushed them off. His vision was Indian unity, with a Hindu subtext; and his was the only right vision. The dalits, like the Muslims, should do what he told them to; and if they were beaten or oppressed or saw their families killed or their homes burned, they should accept it all in the spirit of ahimsa—exactly the advice he gave to the Jews in Hitler’s Reich. Such claims of absolute truth and absolute uncompromising rightness—my way or the highway—are characteristic of cult messiahs. At any rate, Gandhi was anything but a hero to the untouchables.

As for other characteristics of messiahs, one thing you cannot say is that Gandhi raked in the dough and lived the high life. He practiced what he preached: let himself be beaten without fighting back, spent years in jail, cleaned toilets in solidarity with the dalits, and genuinely lived an ascetic life—and yet, mean-spirited as I feel in saying this, there was something ostentatious about his asceticism. As his close friend the poet Sarojini Naidu slyly pointed out, it cost a fortune to keep Gandhi in poverty.

On the sexual side, his idiosyncrasies are well-known, and caused considerable embarrassment to his allies and family. At the age of 37, he informed his long-suffering wife that he (and she) had just sworn off sex forever, as he had taken a vow of brahmacharya, or celibacy-with-benefits, the benefits including an increase in yogic powers, purity, and dominion over self. Like other cult messiahs, he sought to control his followers’ sexuality, demanding celibacy even between married couples on the ashram. Later in life, to test his self-control, he performed what he called “experiments” in chastity, as part of his own spiritual journey and to recharge his satyagraha: sleeping naked with one or two similarly naked women in his bed, including teenaged relatives. Though cuddling the guru was clearly regarded as an honour, the practice was also a bizarre form of sexual exploitation, with damaging long-term effects on the women involved.

Fast forward to the consequences of his vision. Most of all, Gandhi opposed partition—yet his determination to realize Ram Rajya virtually guaranteed that partition would happen. The ugly events that followed partition—mass refugee migrations, ethnic cleansing, up to a million deaths, the later tragedies in Bangladesh, the ongoing ugly situation—may have played out very differently if Gandhi had not had the power to push things in the direction of his impossible dream.

But put it all together, and Gandhi comes off as a charismatic autocrat with a standard millenarian, revitalizing vision to be achieved through magical means. Ahimsa was India’s Ghost Dance, a magic to rid the land of the white man and bring on the new millennium. If one lived in the Truth, maintained purity of body and spirit, and embraced nonviolence, one would, by definition, win any conflict, even if one ended up homeless, raped, battered, or dead. Consider his comments on various groups under threat:

[1938: The Jews] The calculated violence of Hitler may even result in a general massacre of the Jews by way of his first answer to the declaration of such hostilities. But if the Jewish mind could be prepared for voluntary suffering, even the massacre I have imagined could be turned into a day of thanksgiving and joy that Jehovah had wrought deliverance of the race even at the hands of the tyrant.

[1940: An Appeal to Every Briton] I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions. Let them take possession of your beautiful island, with your many beautiful buildings. You will give all these but neither your souls, nor your minds. If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourself man, woman and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them.

[1947] “I would tell the Hindus to face death cheerfully if the Muslims are out to kill them. I would be a real sinner if after being stabbed I wished in my last moment that my son should seek revenge. I must die without rancour…You may turn round and ask whether all Hindus and all Sikhs should die. Yes, I would say. Such martyrdom will not be in vain.” (Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Vol.87:394-5)

To me, these look more like calls to victimhood than to victory, granting a free pass to tyranny and injustice, and—like any religious flummery—making empty promises of spiritual or postmortem rewards.