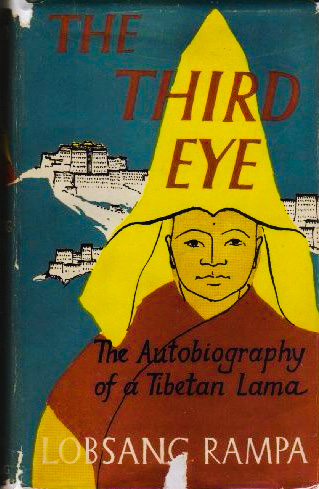

In 1956, a volume of strangely folksy esoterica hit the bestseller list worldwide, and provoked a wave of interest in things Tibetan and the spiritual ways of the mysterious East: The Third Eye. The autobiography of a Tibetan Buddhist lama named T. Lobsang Rampa—the T. stands for “Tuesday”—it described life in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery from the inside, while also delivering hefty helpings of Eastern wisdom.

In 1956, a volume of strangely folksy esoterica hit the bestseller list worldwide, and provoked a wave of interest in things Tibetan and the spiritual ways of the mysterious East: The Third Eye. The autobiography of a Tibetan Buddhist lama named T. Lobsang Rampa—the T. stands for “Tuesday”—it described life in a Tibetan Buddhist monastery from the inside, while also delivering hefty helpings of Eastern wisdom.

Young Lobsang, it seems, was a feisty child, and not at all saintly, but fated for greatness nonetheless—specifically, to spread the light of the Tibetan masters to the unenlightened West. But first, he was subjected to rigorous training from the age of seven, both in spiritual and medical matters, augmented by a procedure to give him special psychic powers: the drilling of a mystical “third eye” into his forehead. And he met a yeti, and his own mummified body from a previous incarnation, and had many other uncomfortable and revelatory adventures as well.

Alas, both Tibetans and Tibetan scholars were highly suspicious, because this Tibetan Buddhist seemed to know very little about Buddhism and even less about Tibet. Inevitably, comparisons were made with Madame Blavatsky’s pseudo-Tibetan effusions. One of his critics—Heinrich Harrer, author of Seven Years in Tibet, and a personal friend of the Dalai Lama—went so far as to hire a private detective, who came up with revelations of a very different sort.

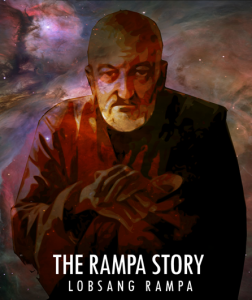

Dr. T. Lobsang Rampa was the recently assumed legal name of a struggling writer called Cyril Henry Hoskin, born in 1910 as the  son of a Devonshire plumber, and with a patchy employment history that included surgical fitting and being the secretary of a correspondence school. He had never been to Tibet. He spoke no Tibetan. He certainly did not look Tibetan. And yet he insisted he was not lying about his inner Tibetan-ness. Annoyed at the nasty suspicious minds of the British press, who for some reason insisted on regarding him as a charlatan, he moved to Ireland, and thence to Ontario, where he produced the book that he hoped would answer and silence his critics: The Rampa Story.

son of a Devonshire plumber, and with a patchy employment history that included surgical fitting and being the secretary of a correspondence school. He had never been to Tibet. He spoke no Tibetan. He certainly did not look Tibetan. And yet he insisted he was not lying about his inner Tibetan-ness. Annoyed at the nasty suspicious minds of the British press, who for some reason insisted on regarding him as a charlatan, he moved to Ireland, and thence to Ontario, where he produced the book that he hoped would answer and silence his critics: The Rampa Story.

Most of this volume, which came out in 1960, recounted Rampa’s adventures in the war and after, including some very nasty experiences in postwar Russia and western Europe, crewing on ships in the Atlantic, and being an underpaid hotel flunky sleeping rough in New York. All of these adventures, on top of torturous times in Japanese POW camps and surviving the nuking of Hiroshima, understandably took a toll on his body; and yet, he still had an important mission ahead of him, a world-changing messianic mission to the benighted West. Clearly he needed a new body, one that was not so weakened by suffering, and yet was somehow harmonically congruent. Enter Cyril Henry Hoskin.

The story goes that Rampa’s handlers on the astral plane had had their eyes on Hoskin for some time, as a potential body-donor. Then Hoskin fell out of a tree and hit his head hard enough to receive a mild concussion; and while he was in a daze and having an out-of-the-body experience, the phantasm of a saffron-robed monk materialized in a bright light beside him. The monk wanted to make a deal on Rampa’s behalf: the use of Hoskin’s body, in return for a huge whack of good karma, and permanent residence in a sort of Club Med on a different (and much nicer) astral plane. Hoskin, tired of the life he was living, agreed to the swap. Rampa, as instructed, made his way back to Tibet so his original body could be safeguarded by the monks while it replaced Hoskin’s body, molecule by molecule, over a period of seven years. He also paid an out-of-the-body visit to Hoskin, to finalize the details of the swap—apparently, Hoskin needed to grow a beard.

The story goes that Rampa’s handlers on the astral plane had had their eyes on Hoskin for some time, as a potential body-donor. Then Hoskin fell out of a tree and hit his head hard enough to receive a mild concussion; and while he was in a daze and having an out-of-the-body experience, the phantasm of a saffron-robed monk materialized in a bright light beside him. The monk wanted to make a deal on Rampa’s behalf: the use of Hoskin’s body, in return for a huge whack of good karma, and permanent residence in a sort of Club Med on a different (and much nicer) astral plane. Hoskin, tired of the life he was living, agreed to the swap. Rampa, as instructed, made his way back to Tibet so his original body could be safeguarded by the monks while it replaced Hoskin’s body, molecule by molecule, over a period of seven years. He also paid an out-of-the-body visit to Hoskin, to finalize the details of the swap—apparently, Hoskin needed to grow a beard.

“You will have to grow a beard,” I said, “for if I occupy your body, mine will soon be substituted, and I must have a beard to hide the damage to my jaws. Can you grow a beard?”

It seems Hoskin could. And then, all that remained was for him to give himself another knock on the head by falling out of a tree again; the transmigration of souls was accomplished in an operation involving cutting and retying the silver cord that bound body to soul. So, sure, the body was the body of an Englishman, but the soul was the soul of a 100% genuine Tibetan Buddhist lama.

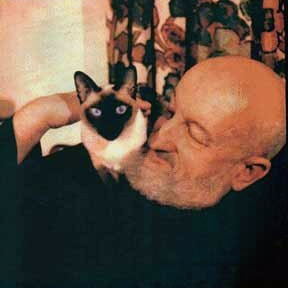

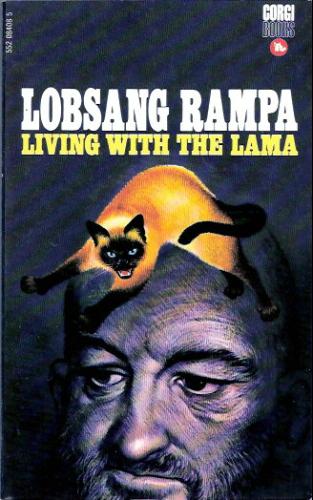

Some people howled with laughter at this; others, predictably ate it up and came back for more. Hoskin/Rampa went on to write around twenty books on occult subjects, one of them being telepathically dictated to him by one of his cats, (Mrs.) Fifi Greywhiskers, whose style was oddly reminiscent of his own. In Canada, he ran an ashram for a bit in Toronto; then he moved to Calgary, where he died in 1981, seventy-one years old by the world’s unimaginative reckoning, but 160 by his own. Quite a bit of his fortune was left to his cats, and cat charities. Meantime, his version of the “third eye” concept entered popular culture and the English language, and devoted fans continue to disseminate his teachings on the internet. His books still sell.

around twenty books on occult subjects, one of them being telepathically dictated to him by one of his cats, (Mrs.) Fifi Greywhiskers, whose style was oddly reminiscent of his own. In Canada, he ran an ashram for a bit in Toronto; then he moved to Calgary, where he died in 1981, seventy-one years old by the world’s unimaginative reckoning, but 160 by his own. Quite a bit of his fortune was left to his cats, and cat charities. Meantime, his version of the “third eye” concept entered popular culture and the English language, and devoted fans continue to disseminate his teachings on the internet. His books still sell.

Now, I do remember hearing about Lobsang Rampa when I was a child, though I thought at the time it referred to a kind of tea. I was never interested enough to read the books, assuming they would be deadly-dull expositions of pseudo-eastern philosophy, intentionally obscure, good only for helping one overcome possible bouts of insomnia. Little did I know that Lobsang Rampa was in fact a trained action hero, a two-fisted he-man, and anything but a pacifist, lurching from adventure to violent adventure, and always winning. Some highlights, from my recent perusals:

“Slippery swab, eh?” he grunted, reaching out in an attempt to get my throat in a strangle-hold. Old Tzu, and others in far-off Tibet had well prepared me for such things. I dropped, limp, and Butch’s momentum carried him forward. He tripped over me and smashed his face on the edge of the fo’c’sle table, breaking his jaw and nearly severing an ear on a mug which he broke in his fall. I had no more trouble with the crew.

Violently the swarthy man erupted from the ground, like a rubber ball bouncing. Dashing into the workshop he picked up a steel bar with a claw on the end, a bar used for opening packing cases. Rushing out, yelling oaths, he swung at me, trying to rip my throat. I fell to my knees and grabbed his knees and pushed. He screamed horribly, and fell to the ground with his left leg broken. The steel bar left his nerveless hand, skidded along the ground, and clanged against metal somewhere. “Well, Boss,” I said, as I rose to my feet. “You are not Boss of me, eh? Now apologize nicely, or I will beat you up some more. You tried to murder me.” “Get a doctor, get a doctor,” he groaned, “I’m dying.” “Apologize first,” I said fiercely, “or you will want an undertaker.”

He snatched up a bottle, knocked off the neck against a wall, and came at me with the raw, jagged edge aimed straight at my face. I was tired, and quite a little cross. I had been taught fighting by some of the greatest Masters of the art in the East. I disarmed the measly little fellow—a simple task—and put him across my knees, giving him the biggest beating he had ever had. Marie, hearing the screams, dashed out from her bed and now sat on the stairs enjoying the scene! The fellow was actually weeping, so I shoved his head in the print-washing tank in order to wash away his tears and stop the flow of obscene language. As I let him stand up, I said, “Stand in that corner. If you move until I say you may, I will start all over again!” He did not move.

Nor was Rampa’s physical prowess the only thing to impress me as I worked through some of the early books. Not only a doctor, an engineer, a pilot, a holy man, and a fighter, but a linguist! No, he could not speak Tibetan—he told his publisher he had hypnotically expunged Chinese and Tibetan from his mind, so as not to reveal secrets while under torture by the Japanese—but my, how he could record the peculiarities of English dialects:

Mac stepped forward to me, “Ah, Laddie,” he said, “ye’ve done yer eight hours. Be off with ye. Tell the Steward Ah want ma cocoa as ye step by.”

“Wassamadderwidyabud? Disisnooyoik!” said a crude voice behind me. Turning, I saw a policeman glaring at me. “Any crime in stopping?” I answered him. “Awgitmovin!” he bellowed.

“Git crackin’, chum,” said the fireman, handing me a battered shovel and rake. “Clean out them there ‘oles of clinker. Take ’em on deck and dump ’em. Look lively, now!”

“Gerhumping Golliwogs!” exclaimed Miss Ku in awe, “The guy has broken out the window frame!” [Note: Miss Ku is a cat.]

Now, at some point, Rampa’s style began to sound awfully familiar, both in dialogue and events. Hollywood cliches… B-movie and pulp plots… terrible one-liners… bouncing around from genre to genre, from hardboiled noire, to ‘50s sf, to spy thrillers and war thrillers and monster thrillers, all seasoned with Fu Manchu mysticism, and even (in the case of Mrs. Greywhiskers’ contribution) what can only be characterized as “kitty porn.” Large parts read like fragments of attempted short stories, or sketches of never-to-be-written novels, stitched together with painfully awkward segues. And through it all, as aristocrat, messiah, healer, and superhero, strode the towering figure of T. Lobsang Rampa, like a huge shadow cast by the frail and unassuming Cyril Henry Hoskin.

Which is when it hit me. The oeuvre of T. Lobsang Rampa was more than just a literary scam with strong cultish aspects – it was, perhaps, the most successful Mary Sue since the autobiography of L. Ron Hubbard.