So what is the difference between a personality cult and a messianic cult? This is not a riddle, it’s a serious question – and the correct answer is, as far as I can see, structurally they are pretty much the same thing. Today I want to check off the messianic characteristics of one of the most bizarre personality cults of recent times: the cult of the late Saparmurat Niyazov, glorious leader of Turkmenistan from 1985 until his death in 2006.

So what is the difference between a personality cult and a messianic cult? This is not a riddle, it’s a serious question – and the correct answer is, as far as I can see, structurally they are pretty much the same thing. Today I want to check off the messianic characteristics of one of the most bizarre personality cults of recent times: the cult of the late Saparmurat Niyazov, glorious leader of Turkmenistan from 1985 until his death in 2006.

Turkmenistan was one of the last Soviet republics to secede from the USSR, in 1991. The majority of the population of just over five million is religiously Muslim and ethnically Turkman, with small Uzbek, Persian and Khazakh minorities. Niyazov was the Soviet party boss who had taken control in 1985 and retained it in 1991, and if anything the transition made him more powerful.

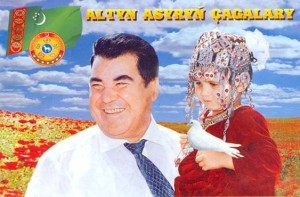

In 1992, he gave himself the title of Turkmenbashi, meaning the leader (or father) of all Turkmen. In 1999, through a decree of his hand-picked puppet parliament, he became president for life—a common move for dictators wishing to preserve a fiction of democracy. His cemented his hold by making himself the centre of a personality cult of the sort that often develops in totalitarian states, aided by iron control of the media, the borders, and the police. But this one went even farther than most.

Niyazov plastered the nation with self-portraits—again, not an unusual activity for totalitarian dictators. But Niyazov’s portraits leaned towards gold-plated larger-than-life heroic statuary, like the one crowning his grandiose “Neutrality Arch” – a massive 40-foot gold-plated figure, winged and waving, and motorized to turn slowly through the day, so as always to face into the sun. There were so many of these overgrown Oscars, and so many posters and billboards of the leader’s face, that one visitor said being in Turkmenistan was like living inside Niyazov’s personal photograph album. In fairness, though, it should be pointed out that not all the statues were of himself—a few were of his mother. Anyway, on a notional cult checklist, we can certainly check off narcissism.

The grandiose architecture is another tipoff. Like Hitler, who spent many happy hours playing with Speer’s models of a fabulous new Berlin, Niyazov made a hobby of commissioning astonishing buildings and ambitious boulevards, lavishly supplied with fountains and artificial lakes although Asgabat is in the middle of the desert. And how was this funded? The same way that Dubai, for example, funds its architectural follies.

Turkmenistan sits on huge energy reserves. That means huge revenues on the one hand; and kid-glove treatment of whoever happens to be in charge, by oil companies and foreign governments who want in. As usual, those revenues were treated more or less as private income by Niyazov and his ex-KGB inner circle. Meantime, public spending was mostly on Niyazov’s pet projects and monuments to himself, while the people slid into poverty, the infrastructure crumbled, and public services were cut back. For example, most hospitals were closed, pensions cut, medical personnel fired by the thousands, the state education system eviscerated, and all libraries outside Asgabat were closed on the grounds that the people were illiterate anyway, or soon would be. Thus, the next item we can check off on the list is the unequal distribution of resources, with the cream rising straight to the top, and a good bit being lavished on showy public white elephants.

Next on the list: isolation from outside influences. Control of the media is pretty much a given for a personality cult, since the media make up the toolkit used to build such a cult, and this case is no exception. Niyazov did his very best, and with considerable success, to cut Turkmenistan off from the rest of the world. He banned internet cafes and drastically limited private access to both internet and satellite communications. At the same time, he exercised extraordinary control over the public media, estimated by human-rights watchdog organizations as being the third most restrictive in the world, after North Korea and Burma. Television and radio boiled down to extended versions of the Turkmenbashi Show, with his little icon ever present in the corner. All foreign print media were banned. The internal print media were viciously monitored. The slightest departure from Turkmenbashi worship was treason, and the offender might well disappear into prison and torture, fatally in at least one famous case

Was there a millenarian subtext? I think so. Turkmenbashi’s stated agenda was to revitalize Turkmen culture and create a new, better, more unified and shining world within the borders of Turkmenistan—after first, of course, getting rid of all tawdry vestiges of the old world. And like millenarian movements in general, it was divisive and demonizing: all external influences, for example any foreigners who were not there with checkbook in hand to do business, were evil. All internal dissent was not just treasonable, but evil. Turkmenistan had not only to be purged of those, but purged of leftovers and reminders of past foreign influence. Only thus, and with properly retrained minds, could the nation follow its visionary leader into a glorious Turkmen future. It is particularly in situations like these that nationalist and religious agendas are shown to be much the same thing.

Was there a millenarian subtext? I think so. Turkmenbashi’s stated agenda was to revitalize Turkmen culture and create a new, better, more unified and shining world within the borders of Turkmenistan—after first, of course, getting rid of all tawdry vestiges of the old world. And like millenarian movements in general, it was divisive and demonizing: all external influences, for example any foreigners who were not there with checkbook in hand to do business, were evil. All internal dissent was not just treasonable, but evil. Turkmenistan had not only to be purged of those, but purged of leftovers and reminders of past foreign influence. Only thus, and with properly retrained minds, could the nation follow its visionary leader into a glorious Turkmen future. It is particularly in situations like these that nationalist and religious agendas are shown to be much the same thing.

Another item on our checklist is a stream of increasingly bizarre and idiosyncratic commandments, with penalties: check. Niyazov issued a stream of laws and proscriptions based on his somewhat eccentric opinions, essentially enshrining his pet peeves in law. A few examples:

- Nobody in the capital could have more than one cat or dog.

- Men had to be cleanshaven and short-haired. He encouraged women to wear their hair in braids, because he liked braids.

- TV presenters could not wear makeup, because he had trouble telling their genders apart when they did. Which is where moustaches might actually have helped.

- Gold fillings were forbidden.

- Jehovah’s Witnesses were banned, and Hare Krishnas were banned from collecting at airports—which just goes to show that nobody is all bad. But there is a lot of evidence for religious persecution that didn’t make it into the official edicts.

- Car radios and recorded music at concerts were banned because he didn’t like them. Ballet, opera and the circus were banned because he thought they were indecent.

- By his edict, adolescence was extended to age 25, and old age was redefined as starting at 85. Which is part of how he justified cutting the pensions.

- Aside from the usual namesake airports, highways and towns, he renamed the months for himself, his mum, and various culture heroes he wished to promote. Also, Monday became Turkmenbashi Day, and his mother’s name replaced the word for bread. And so it went.

On the positive side, he decreed that energy, bread, salt and a rice ration would be free to all citizens, a measure that looksremarkably like the corn dole of Imperial Rome; and he allowed booze, though not public smoking and chewing gum. When he became the Turkmenbashi, he abolished the death penalty, and pardoned hundreds of common criminals annually during a Muslim festival, though never the ones jailed for so-called political offenses. This benevolence was in a country known for a muzzled press, a reign of terror by ubiquitous secret police, concentration camps for so-called dissidents and their families, and the documented use of torture. So, we see a mixed message of giving with one hand, and bashing with the other, reminiscent of the loving but abusive father-role played by cult leaders like Jim Jones.

Next on the checklist is a holy writ, regarded as divine wisdom from the lips of the messiah, and Niyazov obliges here, too. He wrote down exactly what a good Turkmen should be, and then made damn sure everybody in the country read it. His very own holy scripture was a little book known as the Ruhnama, meaning something like the “Message to the Soul”. It laid out the Great Leader’s recipe for moral, spiritual and ethnic goodness, in a chaotic mess of folk wisdom, semi-religious ideology, autobiography, Turkmenocentric pseudohistory, and Niyazov’s own ramblings on the beauty of the landscape. Total blather to outsiders—but to insiders, the greatest book ever written. Or else.

Next on the checklist is a holy writ, regarded as divine wisdom from the lips of the messiah, and Niyazov obliges here, too. He wrote down exactly what a good Turkmen should be, and then made damn sure everybody in the country read it. His very own holy scripture was a little book known as the Ruhnama, meaning something like the “Message to the Soul”. It laid out the Great Leader’s recipe for moral, spiritual and ethnic goodness, in a chaotic mess of folk wisdom, semi-religious ideology, autobiography, Turkmenocentric pseudohistory, and Niyazov’s own ramblings on the beauty of the landscape. Total blather to outsiders—but to insiders, the greatest book ever written. Or else.

From its publication in 2001, it spread by decree into every household in the land, shouldering other books out of bookshops, and being treated as equal to the Koran in its power and significance—which is serious in a Muslim nation. The idea was that it would soon shape the minds of all the citizens into a correct uniformity, so everybody would live happily together in this Turkmen Utopia. Again by decree, it was adopted as THE textbook for education at all levels, with pupils spending up to three hours a day studying and memorizing it. It even had its own statue: a huge mechanical Ruhnama that opened up every night at 8pm, while a passage was read out on loudspeakers. September was renamed in its honour. In 2003, partly on the strength of the Ruhnama, Turkmenbashi began to be honoured not just as the President for Life, but as a prophet.

And it was not enough just to be seen reading it. Everybody was tested on it—as part of school exams, or to qualify for government employment, or even to get a driver’s license—on the theory that, if you had not internalized the wisdom of the Great Father, you would not be a good driver. And if you were foolish enough to be seen not appreciating the book enough, you and your family risked anything up to loss of jobs, jail, torture, or concentration camp. Speaking as a writer, I have to say, that’s ONE way to deal with bad reviews. And as for the market share and visibility on the bookstore shelves: J.K.Rowling, eat your heart out.

It is interesting to see how Niyazov excused himself for the statues, the posters, and the constant diet of adulation and flattery: it was not for him, he did not want it, would rather not have it—it was all “what the people wanted.” And he added, “If I were a worker and my president gave me all the things they have here [for free] in Turkmenistan, I would not only paint his picture, I would have his picture on my shoulder or on my clothing.” Which might have been the subject of an edict eventually, except that Niyazov died in December 2006.

was not for him, he did not want it, would rather not have it—it was all “what the people wanted.” And he added, “If I were a worker and my president gave me all the things they have here [for free] in Turkmenistan, I would not only paint his picture, I would have his picture on my shoulder or on my clothing.” Which might have been the subject of an edict eventually, except that Niyazov died in December 2006.

What happened to him? He was only 66. Officially, he died of cardiac arrest. Unofficially, we may never know, but the stakes were high, a number of surrounding circumstances were suspicious, and it’s possible he was dead for a few days before his death was made public.

His successor, Gurbanguly Berdymuhamedov (rumoured to be Turkmenbashi’s illegitimate son, or possibly his personal dentist) started off like a typical pious heir. He did not distance himself from his “dad’s” excesses, but gave him a slap-up state funeral, and then quietly began to repeal some of the great man’s wilder edicts, to slightly downplay the Ruhnama, and to remove some of the more florid statues, including the giant on Neutrality Arch; but he has also begun to replace them with his own. He’s even writing his own book. There are signs that he is simply weaning the nation off one personality cult, only to offer them another, as Stalin did after Lenin died. But there is little sign that anything is different in the corruption and corrections departments. Plus ca change. This is a country to watch with interest.

His successor, Gurbanguly Berdymuhamedov (rumoured to be Turkmenbashi’s illegitimate son, or possibly his personal dentist) started off like a typical pious heir. He did not distance himself from his “dad’s” excesses, but gave him a slap-up state funeral, and then quietly began to repeal some of the great man’s wilder edicts, to slightly downplay the Ruhnama, and to remove some of the more florid statues, including the giant on Neutrality Arch; but he has also begun to replace them with his own. He’s even writing his own book. There are signs that he is simply weaning the nation off one personality cult, only to offer them another, as Stalin did after Lenin died. But there is little sign that anything is different in the corruption and corrections departments. Plus ca change. This is a country to watch with interest.