A common modern conception about Medieval times is that the Catholic Church was in absolute control of the hearts and minds of European Christendom, and there is no doubt that it was very powerful. But it had also become a swollen bureaucracy, rich and corrupt, staffed with many drunken or womanizing clerics. Its Popes—frequently more than one at a time—often seemed to be more concerned with the Church as an instrument of power than as a spiritual institution. The meek, far from inheriting the earth, were at the mercy of their feudal lords and the clergy, as well as plagues, wars, famines, and natural disasters.

Not being stupid, the medieval masses could hardly help but notice the cruelty and injustice of the temporal world, and the fact that the Church was unable to protect them from such woes as epidemics or oppressive masters. It must also be said that the Church did not try very hard. Instead, it was in the interests of both spiritual and temporal powers to push the idea that the world which the meek would inherit was the next one—the one they would go to when they died, assuming they remained obedient to the Church and their masters while they lived. Conveniently, then, it was not the Church’s job to improve the circumstances of this world.

Consequently, resentment against the Church and the clergy could be both murderously intense, and widespread, especially in times of crisis. A large number of medieval messiahs profited from that resentment, offering the miserable peasantry a focus for both their anger and their hopes. Not only are crisis times a seller’s market for millenarian hopes, but messianic pretenders in this period could draw upon the ready-made apocalyptic script deeply embedded in the zeitgeist. Scores of messiahs and millenarian movements are documented in the roughly thousand years of the medieval period, with some fascinating general patterns in how they operated, and how the populace responded.

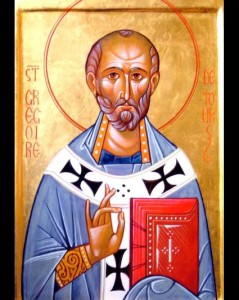

An early example is nameless and faceless, known only from an anecdote in the bloody, enthralling History of the Franks by the sixth-century chronicler Gregory, Bishop of Tours (Book X:25). Gregory places the episode squarely inside an apocalyptic frame: a rain of messianic woes, from balls of fire in the night sky, to earthquakes, an eclipse, cruel plagues and famines sweeping Gaul—and the coming of false prophets.

These are the beginning of sorrows according to what the Lord says in the Gospel: “There shall be pestilence and famines and earthquakes in different places and false Christs and false prophets shall arise and give signs and prodigies in the heavens so as to put the elect astray.”

Gregory’s example of a false Christ is a “man of Bourges,” who went into the forest one day to cut wood, and was surrounded by a swarm of flies which caused him to lose his mind. It is an odd and intriguing detail: did he see a real swarm of flies, or was he having the sort of hallucination that can accompany high fevers or cerebral events? In any case, he spent the next couple of years living as a crazy hermit in the wilderness, wearing animal skins, and doing a whole lot of praying. When he emerged, he emerged as a Messiah, in fact as Christ himself, gifted with the powers of prophecy and healing. He soon built up a following, starting with a woman appropriately named Mary, who passed as his sister and was also divine.

Interestingly, this messiah did not seem to be interested in accumulating personal wealth—only adulation. His followers, who may have numbered up to 3000 by the end, included not just the poor and dispossessed, but even some priests who believed in his divine nature because of his miraculous healings. The self-proclaimed Christ led his growing army through the countryside of Gaul, accepting gifts of gold and fine garments which he would distribute to the poor, and engaging in public rituals where both he and Mary would be worshipped as divine.

His following, not unpredictably, evolved into an army of bandits, robbing travelers they met on the way—though the Messiah was said to distribute all the booty to the poor—and threatening violence to bishops and towns who did not acknowledge the Messiah’s divinity. Naturally, this lawlessness could not be permitted to continue. By subterfuge, the Bishop Aurilius of Puy managed to defeat the Messiah as his army gathered to attack the town, announced by naked, capering messengers. One of the bishop’s own messengers pretended to prostrate himself before the Messiah, and instead caught him around the knees, pulled out a sword, and cut the unfortunate Christ to pieces. Mary was captured alive, however, and tortured until she confessed to the demonic sources of the Messiah’s power.

Their followers were allowed to disperse, but the messiah’s downfall did not affect their faith. As Norman Cohn puts it in his classic work In Pursuit of the Millennium, “Those who had believed in him continued to do so; to their dying day they maintained that he was indeed Christ and that the woman Mary, too, was a divine being.” The chronicler concluded that this Christ was a kind of antichrist, in league with the devil; he went on to say that there were many such pretenders wandering the countryside, whom he also equated with the “false prophets” who would infest the earth in the end times.

Nameless and faceless though he was, this unfortunate Christ is pretty much a template for your basic common-or-garden wandering messiah. Classic features include:

- The messiah, previously unremarkable, spends a period in the wilderness and emerges with a holy or even divine nature. Frequently, the period in the wilderness includes illness and/or madness.

- His claim of holiness is validated by miracles of prophecy and especially of healing.

- He rises in desperate times, and draws his following mostly, but not exclusively, from the poor and desperate.

- He theoretically robs the rich to give to the poor; in practice, he takes from unbelievers to give to the faithful, a form of declaring unbelievers “fair game.”

- His following becomes increasingly militarized, and enters into escalating conflict with established church and secular authorities.

- Authorities respond by destroying him and his closest associates, and a proportion of his following.

- The official verdict judges him to be a false prophet or antichrist, while surviving followers continue to believe and keep the faith.

Versions and variants of this tragic scenario played out scores or even hundreds of times over the next thousand years, and have their close modern cognates: Waco and the Manson Family, for two notorious examples. But as well as these one-man messianic operations, there were numerous larger-scale social movements of a millenarian nature, some of which were sanctioned by the church, while others were regarded as heretical and bloodily rooted out. We’ll look at examples of these next week.