I’m going to fast-forward again, right past one of the big kahunas in the long, checkered history of messiahs, Jesus himself. This is because I want to return to him and some related issues at a later date, when a few more recent messiahs have been properly digested. For the moment, we’ll move on to the Middle Ages, and the seething messianic hotbed of Medieval Europe.

I’m going to fast-forward again, right past one of the big kahunas in the long, checkered history of messiahs, Jesus himself. This is because I want to return to him and some related issues at a later date, when a few more recent messiahs have been properly digested. For the moment, we’ll move on to the Middle Ages, and the seething messianic hotbed of Medieval Europe.

The Middle Ages were certainly an interesting time to be alive, in the sense of dangerous and difficult. The period begins with the fragmentation of the Western Roman Empire in the late fifth century, its territories devolving into scrappy successor kingdoms. It ends in the sixteenth century, with the widespread stirring of new cultural currents: the Protestant Reformation, the Renaissance, the Age of Exploration. In between, there’s a fair amount of Sturm und Drang: warring states and devastating plagues, oppression and superstition, and a number of what look to modern eyes like episodes of pathological madness, including but not limited to the crusades and the Inquisition. And hanging over it all, good and bad, was the Church.

Christianity—which began as a wildly heterodox set of cults in the first century AD—was adopted by the Emperor Constantine as Rome’s state religion in the early fourth century, mostly as a political move. This did not stop the theologians continuing to wrangle over crucial issues like whether Jesus was of identical substance with God the Father, or only similar substance, the sort of rarefied debate that usually led to bloodshed. However, an interesting thing had already happened to Christianity by the fourth century: it had routinized—that is, it had moved into the mainstream, and taken on institutional trappings.

Along the way, a wide streak of apocalyptic, millennialist belief had become an inextricable part of the Christian mix. From the Judean scriptures and the Jesus cult, Christianity had inherited the idea of a messiah who would lead the righteous in making a better world—originally conceived of as being on this earth, in this life. The messiah’s ignominious death did not mean the dream also died; it just got deferred until that glorious future moment when the messiah would come back. Cognitive dissonance is a wonderful thing.

In the early centuries of Christianity, that second coming was considered imminent, and some powerful ideas about how it would happen came in the same package with the Jewish scriptures. The general name is eschatology, the study of the last days and the end of the world, as revealed in sacred texts and prophecies, and it is by no means a dead field of study. Modern fundamentalist evangelicals who are looking eagerly towards an imminent rapture and Armageddon use the same texts, and many of the same interpretations.

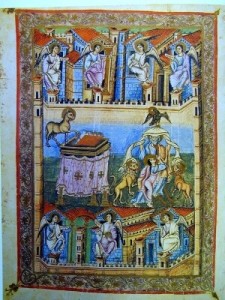

The medieval version had several important sources. The first involved prophecies taken from Judean scriptures, particularly the Book of Daniel and the gloomier of the major prophets, dating to the last couple of centuries BC. It is from here that much of the imagery of horned beasts and antichrists and statues with feet of clay and so forth originated.

Second, there was the specifically Christian tradition, exemplified by the Revelation of St. John the Divine, a psychedelic account of the last days to come, full of seals and trumps and weird happenings, fiery martyrdoms, whores of Babylon, and horsemen of the apocalypse. This is the strand most familiar in the modern West, if only through such horror movies as The Omen and Rosemary’s Baby.

Then there were the Sibylline Oracles, which did not make the cut when the canon was selected, but which were widely read and influential throughout the whole of the Middle Ages. Sibylline prophecies – that is, oracular pronouncements in Greek hexameter by wild-eyed prophetesses—were a long tradition in pagan Rome, collected and consulted from about the 5th century BC. The genre was adapted by Alexandrian Jews as early as the 2nd century BC, and then readapted by early Christian writers, and much quoted by the early Church fathers. The Christian oracles introduced a figure formally referred to as the “Emperor of the Last Days” – a magnificent warrior-king who would sweep away the sinful, bring about the triumph of Christianity over all other creeds and nations, and prepare the way for God to return and reestablish his kingdom. And then, of course, everybody would live happily ever after. These prophecies had wide currency, and were taken very seriously indeed.

As for the Emperor of the Last Days, Constantine himself was thought at first to be the fulfillment of the Sibylline oracles, having just bumped Christianity into the driver’s seat. But then he died, and his death meant that the Christian world had to wait a bit longer. In the meantime, putting these various sources together, the masses of Europe developed a widespread folk belief system centered around apocalyptic hopes and fears, especially among the numerous disadvantaged and oppressed, for whose comfort the church did very little. Such apocalyptic scenarios were not limited to Christians, but a specific scenario was constructed from the above-mentioned sources, along the following lines.

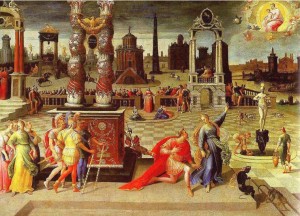

The world was desperately wicked, having spiraled down from a state of grace into a state of sin. God was indeed intending to return, but before that could happen, this cesspit of depravity would first need to be cleansed of infidels and sinners by a warrior-saviour, the Emperor of the Last Days. And before he could charge onto the scene, things would have to get even worse, with a rain of “messianic woes”: wars and rumours of war, famines, plagues, earthquakes, and many false prophets. The Emperor of the Last Days would rally the righteous and declare war on heretics, infidels, false prophets, and the ungodly—which, in many medieval eyes, included the corrupt and desperately wicked hierarchy of the Church. The hero’s chief adversary would be his opposite number, the Antichrist, who might present himself as being on the side of good, but would in fact be allied with demonic powers. The slightly comical effect was that religious leaders, heads of state and rival messiahs routinely accused each other of being the Antichrist.

At any rate (continuing with the millennial expectation) conditions on Earth, already awful, would reach a crescendo of misery and blood as the Emperor of the Last Days combined forces with godsent disasters and punishments to purge the world of all unbelievers. Eventually, when all the unbelievers had been righteously massacred, the Emperor of the Last Days would reclaim Jerusalem, and welcome the return of Christ and the beginning of Heaven on Earth—literally.

Note that—unlike the zombie, nuclear, and meteor-strike apocalypses of current popular culture—it was not so much the end of the world that was prophesied, but the renewal of Earth’s original perfection. Crucially, the mass of medieval believers still expected it to happen imminently, and on this Earth, resulting in justice and prosperity for the oppressed faithful, and bloody vengeance on the fat cats at the top of the church hierarchy and the social pyramid. It was at heart a revolutionary hope, which marked an ironic return to the revolutionary nature of the original Jesus cults.

Another critical point: these prophecies, particularly the Sibylline oracles, had far-reaching effects on Europe’s attitude towards Islam in the Middle Ages, and directly contributed to the motivation behind the Crusades. Christ would only return to a world cleansed of unbelievers, and only after the warrior-messiah had taken Jerusalem and—in some variants—rebuilt Solomon’s Temple. For that alone, the pseudo-Sibyls have much to answer for.

Who was this warrior-messiah going to be? These were hard times—so hard, that every generation was able to look around and see the first conditions of the Sibylline prophecies apparently fulfilled, in terms of desperate wickedness, disaster, and deepening despair, the rain of messianic woes. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a rain of messianic pretenders, some from the grassroots, and some from the highest levels of the elite.

A new ruler might be greeted with the popular hope that he would turn out to be the Emperor of the Last Days. If he was wise and good, but did not fulfill the prophecy—and of course, none did—he might be regarded as a precursor, one who was preparing the way for the prophesied warrior-messiah, and the people would hope for better luck next time. His enemies, meanwhile, might well regard him as a potential antichrist, and vice versa.

But an interesting twist developed early on. Impressive candidates for the last-days role could raise such high hopes that the disappointed populace simply could not let go when their champion died without ending the world. Legends grew up around some of them, and three in particular.

Charlemagne (747-814) was the brilliant, charismatic Carolingian who united much of Europe in the late 8th century, in what is called the Holy Roman Empire – though, as Voltaire pointed out, it was neither holy, Roman, nor an empire. Frederick I, also known as Barbarossa (1122-1190), was the Holy Roman Emperor who participated in the Third Crusade with Richard Lionheart, and whose death was a disaster. Greatest of all was his grandson, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick the Second (1194-1250), also known as”Stupor Mundi”, or the “wonder of the world”, for his brilliance, intelligence, goodness, and charisma. He was regarded as a particularly promising candidate, as he was constantly at odds with the Popes, whom the populace widely resented as greedy and corrupt. He was even excommunicated, twice. Eschatological hopes and expectations were exceptionally high when he was alive, though he had an unfortunate habit of negotiating with the Muslims; the disappointment when he died without fulfilling the Sibylline prophecies was particularly sharp.

Here is the fascinating twist: these three all became subjects of the “sleeping hero” legend, a widespread motif that is more familiar to us from, say, the legends of King Arthur, the Hidden Imam, and, oddly enough, Jesus Christ. In this archetypal scenario, the hero is not really dead, but only sleeping; when the appointed time comes, when messianic woes reach another crescendo, he will rise again and return to save the nation, bringing about a better world in the familiar old apocalyptic way. This sleeping hero motif is, in fact, a global phenomenon. Legends of a once and future king, a king under the mountain, a dead hero who is not really dead, are found everywhere. It seems we as a species are reluctant to let go of our heroes.

At any rate, would-be messiahs wanting to start a movement in medieval times had quite a menu to choose from. Quite a number claimed to be one or another of those great Emperors of the Last Days, reawakened, resurrected, and eager to fulfill the Sibylline prophecies at last. Pseudo-Charlemagnes, Barbarossas, and Fredericks, among others, popped up for centuries after the heroes in question died. And it is no coincidence that Hitler chose the name Barbarossa for an operation that was markedly apocalyptic in nature.

Other medieval messianic pretenders, however, took a more direct approach: not precursors of the divinity, not preparers of the way, but divinity in person. We will look at some of those next week.