“Perhaps you, my judges, pronounce this sentence upon me with greater fear than I receive it.”

He said that last week. Now he shivers in the corner of his cell, wondering whether, for once in his life, he could have chosen his words more temperately. What seemed, a week ago, to be a fine mixture of courage and defiance was not absolutely true even then; and now, on the morning of his death, Giordano is beginning to realize just how frightened he is.

The state of being dead will not be unwelcome, for Giordano feels he has nothing to fear from God, whereas his murderers will someday cringe under divine judgment – but the dying itself is a hideous mountain to climb before he can rest. Pain is not something one gets used to, even after seven years in the care of the Roman Inquisition. Giordano has learned that too much courage does not pay. Pain borne in silence leads to more pain, and more, and yet more, until finally one’s screaming point is reached and the questioners are confident they have gained one’s attention.

The morning is February-cold. He could almost, he tells himself, welcome a fire – and at that irony, he laughs for the last time in his life. And then he hears footsteps and voices on the stairs, and he opens his body to the cold as if he could suck it into his pores and store it up against his imminent dire need. The reverend brothers of the Company of Mercy and Pity have returned from their breakfast.

Dignity, he tells himself. Above all else, dignity. And maybe a few words at the stake, words that will be better chosen, more pointed, more memorable, than those words of hasty defiance when judgment was pronounced. Since die he must, he would like to die in a way that men will remember – but what to say? Never mind: for fifty-two years he has been a man of many words, and he is sure his tongue and talent will not fail him at the end.

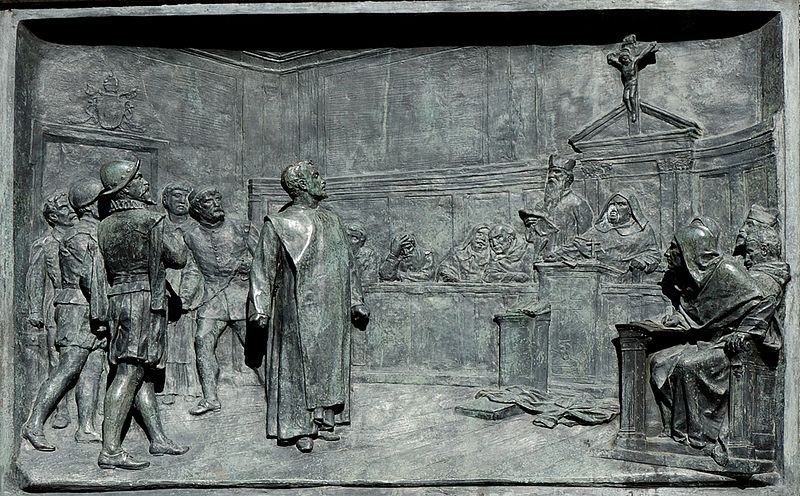

Hooded figures, self-styled dispensers of mercy and pity, hover black in the smoky candlelight: “Giordano Bruno, born Fillipo Bruno of Nola, once of the Brotherhood of the Dominicans – do you know why we are here?”

“Yes, Robert, I know.”

“For the last time: do you recant your heresies?”

Giordano sighs. “I’ve glorified God in my own way, not the Church’s, and that’s all there is.” He pauses to order his words for a last debate with his inquisitor – his life has been a string of spirited debates – but a nail is already point-down on his tongue, and a moment later it is driven home; and even as he tries to scream, a second nail is driven upwards through his lower jaw into the palate. The blood pouring into his throat chokes him into silence. He hardly has attention to spare for the leather-and-iron clamp of the gag.

“Did you imagine we’d let you vomit your heresies in public?”

Now he is in violent motion, jerked along, stumbling and staggering between two of the righteous. He realizes dimly that he has shat himself. Breath and blood struggle for passage in his throat. They pause under the arch of the gate – Giordano sinks to his knees and frantically pulls air in through his nostrils, but the respite is brief. It is Grazio who tears the robe off Giordano’s back, Clemente who wads it up and wipes the scarlet trickles from the underside of Giordano’s jaw. Officially, the heretic’s blood will not have been spilled. Clemente does not clean off the backs of Giordano’s legs, for it is only appropriate that heresy should come to its just punishment naked, smeared and stinking.

Thus – Giordano, all dignity a bitter memory, is hustled naked into the cart and trundled through the streets, freezing in the last dark minutes before a winter dawn. He shivers, and Grazio hisses into his ear: “you’ll be hot enough soon, heretic.” The cart stops on the edge of the Campo del Fiore, the Field of Flowers, where a small but gleeful crowd hugs itself for warmth in front of the high-piled faggots, the premonitory torches. The crowd howls as the procession crosses the square, animal noises, a wallow of pigs, a snapping of dogs, a hooting of Barbary apes. Giordano hears them through his agony – shame sickens him. He digs his naked heels into the cobbles and tries to fight, rearing his head, panicking, eyes wild as a horse’s at the sight of fire. They roll heavenward, up to where God’s little lights are still visible, fixed to the crystal globe of the firmament, obediently rotating around the terrestrial centre of God’s little universe.

Giordano stops fighting. He stares up. He has not seen the stars for seven years. He looks up, up, up, through the mantle of the air and past the moon, beyond the purview of the sun and across the dark void. He shrinks to a particle on a whirling grain of sand. Clemente, another insignificant particle, shoves him from behind. Infinity arches above them. Giordano is entranced. He lets himself be propelled unresisting towards the crowd, the torches, the stake. He is busy trying to number the glitter of the stars, a count that he knows he will never finish. This does not seem to matter. He would shout for triumph if the clamp would let him.

Now they are binding him to the stake, pinching his flesh in the cold coils. He pays no mind. Robert shoves the crucifix almost into his face – he shies from it impatiently. He wants to cry, “Look up, you fools! It’s so obvious! You’ll see I’ve been right all along!” Impossible, alas, with his mouth nailed shut; but he has a strange idea the future will speak for him.

The Company of Mercy and Pity has provided no strangler. With his own hand, Robert plunges the torch into the faggots at Giordano’s feet, and steps well back. Giordano makes no sound, then or ever again. He watches the sky for as long as his eyes last, though the stars begin to fade in the dawn and the smoke thickens over his head. They are so clear to him: other suns, great suns, distant suns blazing down on God’s uncountable worlds, all of them swarming with God’s creatures, an infinite universe filled with the music of a mighty massed choir of spheres.