This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the graduate students in my Psychopathology course. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Mental Health.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular class of mental disorders.

______________________________________________

The journey from PDD to ASD: What’s with all these letters? by Nicole Beasler

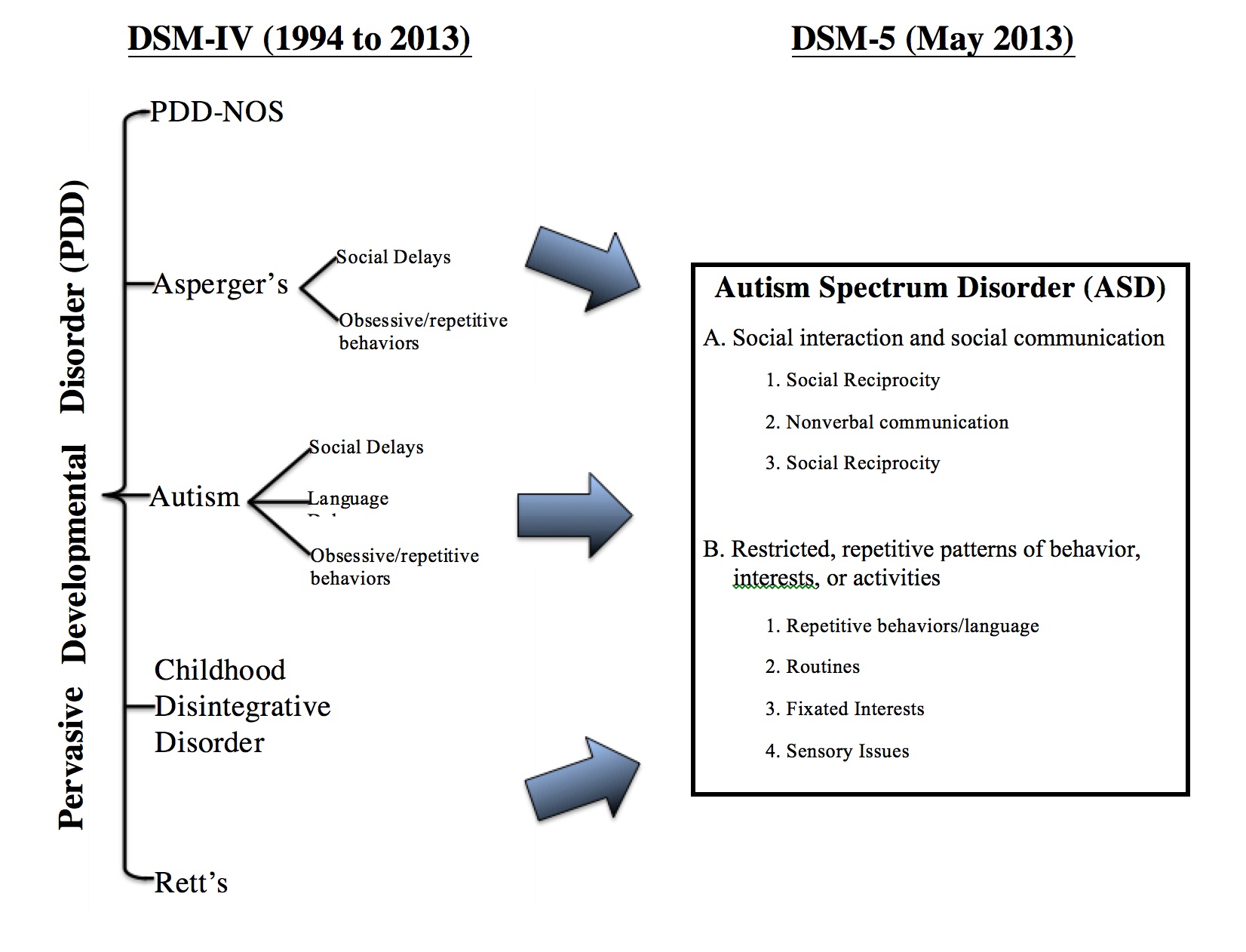

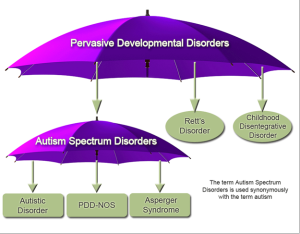

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact Sheet, one of the most important changes in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is the new classification of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Under the previous version, DSM-IV, there were five separate disorders considered to be pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs): autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, Rett’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder, or the catch-all diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS).

What Is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

According to Autism Speaks, the world’s leading autism science and advocacy organization, Autism Spectrum Disorder or ASD is a group of complex disorders of brain development characterized by difficulties in social communication (including verbal and nonverbal) and repetitive behaviors, both in varying degrees; thus, the term “spectrum”. Each individual with ASD is unique and their abilities along the spectrum are also unique – varying from significant disability to being able to live independent lives.

Many people already used the “Autism Spectrum” terminology prior to DSM-5 to describe three of the five subcategories of PDD: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder and PDD-NOS. This would lead you to believe this would be an easy transition for clinicians as well as clients and their families, but that could not be further from the truth.

Many people already used the “Autism Spectrum” terminology prior to DSM-5 to describe three of the five subcategories of PDD: autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder and PDD-NOS. This would lead you to believe this would be an easy transition for clinicians as well as clients and their families, but that could not be further from the truth.

History of Autism in Psychology & the DSM

To really understand all of the confusion over “autism” it is necessary to go back to the beginning of the use of the term in the psychology field. One article that not only covers the new ASD classification, but also provides a great history on the associated disorders is DSM-5 ASD Moves Forward into the Past by Tsai & Ghaziuddin. They point out that the word “autism” was first used in the psychological world around 1911 by Eugen Bleuler to describe a group of symptoms of schizophrenia.

Leo Kanner first coined the term “early infantile autism” in 1943 to describe a condition he had observed in a group of physically normal children he was studying. He noted these children’s inability to develop relationships with others, a delay in their speech development, and repetition of play activities. He believed these symptoms were already evident in infancy, hence his term “early infantile autism”. Much of the blame he felt lay with the parents of these children who obviously had not given them enough love as infants which in turn was one of the causes of the development of this “autistic aloneness” that they suffered from.

At about the same time Hans Asperger, unaware of Kanner’s research, identified a similar condition, now known as Asperger’s syndrome. Asperger’s syndrome was different in one respect: his subjects had no delayed speech development (in fact they seemed to be highly intelligent) but lacking in social skills and exhibiting the repetitive behavior associated with Kanner’s “early infantile autism”. Autism and schizophrenia continued to be linked for many years. It was in the 1960’s before researchers really began to understand the distinction of autistic symptoms from those of schizophrenia.

The first two DSM’s, DSM-I (1952) and DSM-II (1968) did not have a category for Autism or Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD). Children who exhibited autistic-like symptoms were diagnosed under the “schizophrenic, childhood type” label. The first separation of autism was in DSM-III in 1980 when it was distinguished from childhood schizophrenia by adding Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD) with three subcategories: (1) Childhood Onset PDD, (2) Infantile Autism, and (3) Atypical Autism. In 1987 the DSM-III-R added Autistic Disorder and PDD-NOS under the PDD categories.

In 1994 the DSM-IV continued with the scheme used in the DSM-III of using the term Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDDs) but increased the subcategories to five: (1) autistic disorder, (2) Rett’s disorder, (3) childhood disintegrative disorder, (4) Asperger’s disorder, and (5) PDD-NOS. Many people felt this was too many subcategories because many symptoms crossed over from one to the other with the degree or severity of the symptoms being the only difference, making diagnosis at the discretion of the clinician.

- Autism Criteria -6 symptoms from 3 core domains:

- Qualitative Abnormalities in Reciprocal Social Interaction (need 2)

- Qualitative Abnormalities in Communication (need 1)

- Restricted, Repetitive, and Stereotyped Patterns of Behavior (need 1)

- Abnormality of Development at or Before 36 months

- Asperger Criteria: need 2 from A.; none from B.; 1 from C; plus must rule out autism, no language delay; onset criterion not necessary

- PDD-NOS: often a mild version of autism, communication and or RRB symptoms not necessary; onset criterion not necessary

In 2007, the American Psychiatric Association began the process of changing the PDD categorization as it appeared in the DSM-IV by forming a working group to look into the best way to revise the PDD category for the DSM-5. It was concluded that the best approach would be to create one category but have different levels of severity under that category. It was decided to replace the Pervasive Developmental Disorders or PDD term with the term Autism Spectrum Disorder or ASD and use a three-tier level of classifying the diagnosis of ASD based upon severity level. When the DSM-5 was released in 2013 these proposed changes were adopted.

Dr. Walter Kaufmann (one of the members of the DSM-5 Neurodevelopmental Disorders Workgroup summarized the new criteria for ASD as follows:

Currently, or by history, must meet criteria A, B, C, and DA. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across contexts, not accounted for by general developmental delays, and manifest by all 3 of the following:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction

- Deficits in developing and maintaining relationships

B.Restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or activities as manifested by at least two of the following:

- Stereotyped or repetitive speech, motor movements, or use of objects

- Excessive adherence to routines, ritualized patterns of verbal or nonverbal behavior, or excessive resistance to change

- Highly restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus

- Hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of environment;

C. Symptoms must be present in early childhood (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacitiesD.Symptoms together limit and impair everyday functioning.

Along with thsee criteria, the DSM-5 also includes “specifiers” for an ASD diagnosis that include:

- Intellectual disability

- Language impairment (include description of current language functioning)

- Known medical/genetic conditions or environmental factors

- Other neurodevelopmental, mental, or behavioral disorders

DSM-5 also created a three-tier level of classifying the diagnosis of ASD based on severity level.

- Level 1: “requiring support”

- Level 2: “requiring substantial support”

- Level 3: “requiring very substantial support”

The DSM-5 also includes a new diagnosis of Social Communication Disorder (SCD) for those that do not meet all of the social communication criteria and without the restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior for an ASD diagnosis. SCD has been compared by some to the PDD-NOS diagnosis under the previous DSM-IV guidelines.

The chart below summarizes the differences between the DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria:

According to an article on the Autism Research Institute website, many people were very concerned when the proposed changes to the DSM were first revealed. One of the biggest concerns was that some of the people previously diagnosed with one of the pervasive developmental disorders under the DSM-IV criteria would fail to meet the threshold necessary to receive a similar diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder under the new DSM-5 criteria. This was a very real concern for many parents of children with previous PDD diagnosis because of the uncertainty regarding how state and educational services and insurance companies would adopt the proposed changes.

Many studies were done in an attempt to see if people previously diagnosed with one of the five subcategories of PDD under DSM-IV would receive a similar diagnosis of ASD under the new DSM-5 guidelines. The results varied across studies from less than 50% to over 90%, mostly due to varied samples and methods used. One such study done by Young & Rodi concluded that most of the studies’ findings did seem to be consistent, in that it was the higher functioning individuals that were usually omitted from the new ASD diagnosis due to a failure to meet all three criteria under the social-communication domain. These higher functioning individuals would be those previously classified under either Asperger’s disorder or PDD-NOS as compared to the classic autistic disorder. Another paper titled Diagnosing autism spectrum disorder: who will get a DSM-5 diagnosis? Points out that it is possible to get comparable results using the new DSM-5 in relation to the DSM-IV; however, special attention needs to be paid to the subdomains and the levels of severity while considering age and ability level of the subjects.

All of this concern over the new criteria resulted in three very important revisions in the ASD criteria in DSM-5 from the draft criteria that had been circulated for review. These changes were felt necessary to insure that all children or adults currently receiving treatment either through state funded services or private insurance, could continue to receive the same level of treatment. First, the inclusion of the term “by history” was added in the assessment of the diagnostic criteria. Second, a clear “grandfathering in” of existing diagnosis made it clear if an individual had a “well-established” DSM-IV diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, Asperger Disorder, or PDD-NOS, he or she should receive a DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD without the need for re-evaluation. A third and final change was the elimination of the previous rules that had prevented the co-diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or schizophrenia along with a diagnosis of autism.

Conclusions

Regardless of what we chose to call it, autism and research into the causes and the most effective treatment methods for the people who suffer from it will continue to be at the forefront of the psychology community for decades to come. It affects so many children and families not only in the United States, but around the world so it is important that research continues into the causes and one day maybe it won’t matter what it is called, autism, ASD or PDD because it will be a thing of the past. But in the meantime we all need to remember that every person that suffers from ASD has potential and we should do what we can to make sure they are able to reach the full extent of that potential.