This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the graduate students in my Psychopathology course during Spring 2014. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Mental Health.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular class of mental disorders, with one of those focusing on evidence-based treatments for those disorders and the other focused on a particular myth or misunderstanding about mental illness.

______________________________________________

Myths & Misconceptions about Hoarding Disorder by Kelly Jent

How many of us have watched shows like Hoarding: Buried Alive or My Strange Addiction and immediately judged the people on the show? Comments like “Ew. Look at all of that junk in their house… it’s so dirty! How could someone live like that?! That’s disgusting!” tend to surface. As a matter of fact, while writing this and googling different addictions, I said (to my empty house), “Oh, woah that’s weird.” It’s natural to have reactions like that about something that appears so odd to many of us and something that seemingly would be so easy to fix by quitting getting new things, cleaning, stop saving, etc. However, these comments aren’t helping anyone and are only adding to the stigma about people who having hoarding problems. Speaking of stigma, a reoccurring pattern that I noticed while researching obsessive-compulsive related disorders (e.g. hoarding disorder, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder) is that the stigma surrounding them severely misrepresents the reality that the people with the disorders actually live. To the uneducated, the people are “freaks” or “weirdos” and likewise, these disorders just appear “weird” and are dismissed and justified as “being glad you don’t do stuff like that.” Once disorders like hoarding become media-ized, the public assumes they know the in’s and out’s of what goes on; they feel that they know enough to give you the gist of the problem (which most likely consists of subjective judgments rather than empirical evidence), which is all you really need to know anyway, right?

How many of us have watched shows like Hoarding: Buried Alive or My Strange Addiction and immediately judged the people on the show? Comments like “Ew. Look at all of that junk in their house… it’s so dirty! How could someone live like that?! That’s disgusting!” tend to surface. As a matter of fact, while writing this and googling different addictions, I said (to my empty house), “Oh, woah that’s weird.” It’s natural to have reactions like that about something that appears so odd to many of us and something that seemingly would be so easy to fix by quitting getting new things, cleaning, stop saving, etc. However, these comments aren’t helping anyone and are only adding to the stigma about people who having hoarding problems. Speaking of stigma, a reoccurring pattern that I noticed while researching obsessive-compulsive related disorders (e.g. hoarding disorder, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder) is that the stigma surrounding them severely misrepresents the reality that the people with the disorders actually live. To the uneducated, the people are “freaks” or “weirdos” and likewise, these disorders just appear “weird” and are dismissed and justified as “being glad you don’t do stuff like that.” Once disorders like hoarding become media-ized, the public assumes they know the in’s and out’s of what goes on; they feel that they know enough to give you the gist of the problem (which most likely consists of subjective judgments rather than empirical evidence), which is all you really need to know anyway, right?

Wrong.

There are a number of myths surrounding Hoarding Disorder (just referred to as “hoarding” from here on out), but I think in order to know what hoarding is not, it is important to understand what hoarding actually is first. Hoarding is a newly recognized diagnostic category in the DSM-5 in the Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders section. This disorder involves difficulty parting with possessions regardless of what their actual value is. There is a perceived need to save possessions and distress is linked to the idea or process of discarding them, therefore, items accumulate and clutter living areas which takes away from the functionality of the space. The effects of hoarding must also cause significant distress or impairment in different areas of functioning (social, occupational, familial). I stress: significant distress and impairment in functioning is a must for a diagnosis. That being cleared up, on to the misinformation!

One common myth about a person who hoards is that they are lazy, unmotivated, selfish, or gross. This is false. In fact, people who hoard ARE bothered by the clutter and dirt; they just learn to mentally block it out. They also feel shame and embarrassment due to their living situations. Studies have compared the brains of people who compulsively hoard with “healthy” brains and found that compulsive hoarders have decreased activity (less activation) in their anterior and posterior cingulate cortex. Great…but what does that mean? These brain areas are highly responsible for actions such as problem solving and decision making (anterior), spatial orientation, memory, and emotion (posterior). Decreased activity in these areas is likely contributing to the difficulty that people who hoard experience in deciding what to keep and what to throw away. People who hoard are worried that if they discard something they may actually need it someday in the future – so they keep everything from actually valuable items to items that appear meaningless such as dozens of second-hand eyeglasses that are kept “just in case.” With an accumulation of items comes a significant amount of impairment and distress and this is what distinguishes this disorder from regular collecting. Rather than being lazy or unmotivated, individuals simply may not be as able as an average person to carry out certain tasks in order to make decisions and organize things. With this in mind, it is easier to understand that hoarding is largely an information processing issue.

One common myth about a person who hoards is that they are lazy, unmotivated, selfish, or gross. This is false. In fact, people who hoard ARE bothered by the clutter and dirt; they just learn to mentally block it out. They also feel shame and embarrassment due to their living situations. Studies have compared the brains of people who compulsively hoard with “healthy” brains and found that compulsive hoarders have decreased activity (less activation) in their anterior and posterior cingulate cortex. Great…but what does that mean? These brain areas are highly responsible for actions such as problem solving and decision making (anterior), spatial orientation, memory, and emotion (posterior). Decreased activity in these areas is likely contributing to the difficulty that people who hoard experience in deciding what to keep and what to throw away. People who hoard are worried that if they discard something they may actually need it someday in the future – so they keep everything from actually valuable items to items that appear meaningless such as dozens of second-hand eyeglasses that are kept “just in case.” With an accumulation of items comes a significant amount of impairment and distress and this is what distinguishes this disorder from regular collecting. Rather than being lazy or unmotivated, individuals simply may not be as able as an average person to carry out certain tasks in order to make decisions and organize things. With this in mind, it is easier to understand that hoarding is largely an information processing issue.

Now, back to the decreased activation in the posterior cingulate. Many people who hoard experience extreme anxiety when being faced with having to discard items. This is due partly to the unique emotional relationship that they have formed with their possessions. For example, some individuals anthropomorphize objects. For example, they may think that if they throw out the box that a gift came in, it would hurt the box’s feelings. There is also an association with the memory of when they received something or an event surrounding an item. The lower activity in this area of the brain also governs memory and spatial orientation; they need to have things in sight in order to remember where it is. Individuals think that they will lose items or not remember where something is if it is not in clear view which explains the plethora of items stacked from the floor to the ceiling, covering beds and spilling over tables and counters. Another example is the collection of newspapers – by throwing them away, one might forget the information that is inside of them.

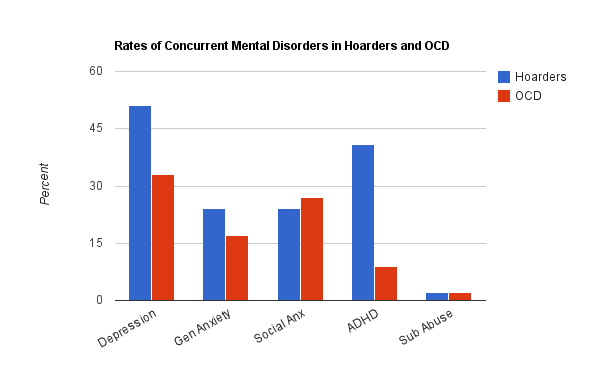

Finally, people who hoard are likely to show signs of other accompanying disorders. Depression and anxiety are the two most common co-morbid disorders. Cory Chalmers of the TLC show ‘Hoarders’ says that 80-90% of all cases that they see on the show are trauma or depression based – meaning that these other experiences trigger the hoarding behavior in individuals as a way to fill a void in their life. Not surprisingly, a higher level of social disability is also found in people who hoard than not.

Finally, people who hoard are likely to show signs of other accompanying disorders. Depression and anxiety are the two most common co-morbid disorders. Cory Chalmers of the TLC show ‘Hoarders’ says that 80-90% of all cases that they see on the show are trauma or depression based – meaning that these other experiences trigger the hoarding behavior in individuals as a way to fill a void in their life. Not surprisingly, a higher level of social disability is also found in people who hoard than not.

I was looking up YouTube videos to go along with this blog and decided to read the comments written about the videos to see what the general attitudes were towards the people in the videos. While, yes, there were some commenters who were positive and/or sympathized for the person featured in the video, the vast majority were negative and downright ignorant and rude. Here are a few gems that I came across.

“That isn’t hoarding she is a slob!”

“That’s so sick. How could anyone live in there?”

“Oh please miss stop making excuses and clean up your nasty house.”

“This ain’t called being a horder, this is called being a lazy bum.”

“Hoarding possessions I can go some way to understanding but the ones who sit in a pile of rubbish are just filthy pigs, that is not hoarding that is blatant slobbery and laziness.”

So… there’s that. I don’t know about you, but I didn’t really get warm fuzzy feelings reading those. The only warm feeling I got was due to my blood boiling. These delightful commenters perfectly illustrate why this disorder is stigmatized, and as you’ve hopefully seen, these comments only reinforce the myth that hoarders are lazy, selfish, unmotivated, or gross. Unfortunately, with the saturation of these shows and comments in the media, I don’t foresee this changing any time soon. However, next time you’re watching a show like this, keep in mind that these individuals in fact are not merely too lazy to clean, but there is most likely other underlying issues that are exacerbating this behavior.