Once upon a time, on an olive-strewn island in a wine-dark sea, beautiful people lived in peace under the rule of the Great Goddess and her matriarchal avatars. The like of their palaces was not seen again until the advent of shopping-mall architecture in the twentieth century; their artistry flowered like the saffron blossoms collected by their luscious bare-breasted maidens. This was Minoan Crete, stronghold of the Matriarchy and the Great Goddess, flower child of the ancient world–until those nasty patriarchal Mycenaeans and even nastier Dorians came along and crashed the party. Oh yes, and there’s something about a volcano on Santorini, and a few earthquakes as well, but the rot really set in when teh menz from the mainland took over.

Except it was almost certainly nothing like that. A depressingly large chunk of the popular conception of the Minoans came straight out of the fertile imagination of Sir Arthur Evans, excavator (and owner) of the Minoan super-site of Knossos for the first forty years of the twentieth century. His speculations, loosely based on the archaeological remains, were transformed into fact by the magic of Evans’ authority and conviction. And then, they were further transformed into reinforced concrete, producing the Knossos which later archaeologists have ruefully nicknamed the “Concretan Civilization.”

Evans’ idyllic vision of ancient Crete was naturally conditioned by late nineteenth-century theorizing about the rise of civilization – at that point, dominated by the idea of “unilineal evolution” from savagery through barbarism to civilization. In one influential variant of this model, a developing civilization was thought to go through a matriarchal stage – something to be grown out of, rather like puberty, after which it would reach the (more advanced) state of being a patriarchy. Evans set his Minoan Eden in the matriarchal phase – and long after mainstream archaeology debunked and abandoned both the model of unilineal evolution and the dreamtime of the Matriarchy, Evans’ idealized creation remained enshrined in the popular imagination. And later in the twentieth century, when Second Wave feminism picked up on the matriarchal/Goddess farrago and began the process of turning it into a New Religious Movement, sunny Minoan Crete became one of their flagship cultures, along with Malta and Catal Huyuk.

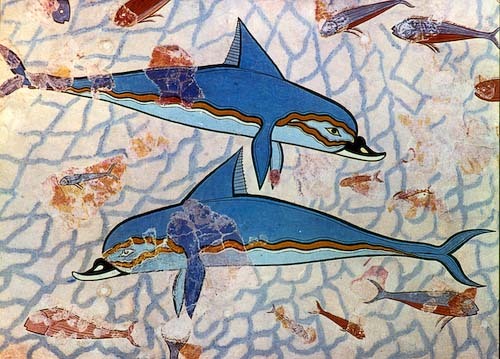

Why am I talking about this? For the past few decades, later generations of archaeologists have been patiently revisiting the data in order to tease out Evans’ speculations-turned-facts from more defensible interpretations. Say goodbye to most of the “Snake Goddesses,” probably forged by the very artisans who helped Evans give shape to his dream; forget the Dolphin Fresco, the Prince of the Lilies and the three pretty ladies with their distinctly Art Deco faces; view Knossos with a skeptical eye. And, according to a recent study, say goodbye as well to the peaceable flower-child nature of the Minoans.

Barry Molloy of the University of Sheffield, in a detailed study of Cretan iconography and artifacts, has concluded on convincing grounds that the Minoans were just about as martial and violence-prone as any of the other ancients, and could no doubt have taught the Mycenaeans a thing or two about warfare – in fact, they probably did. This comes as no great surprise to those of us who were already aware of the Minoans’ perfectly normal dark side – fortifications and guard posts all over the island, lots of weaponry, suggestions of possible human sacrifice – though I suspect it will have little impact on the Great Goddess enthusiasts or the misconceptions that are so deeply entrenched in modern popular culture.

I’m very fond of the Minoans. I wish they could be appreciated for their genuine achievements, the peerless pottery, the lively frescoes, the thriving ports and towns, and not for how they can be exploited to advance some pseudohistorical agendas of our century.