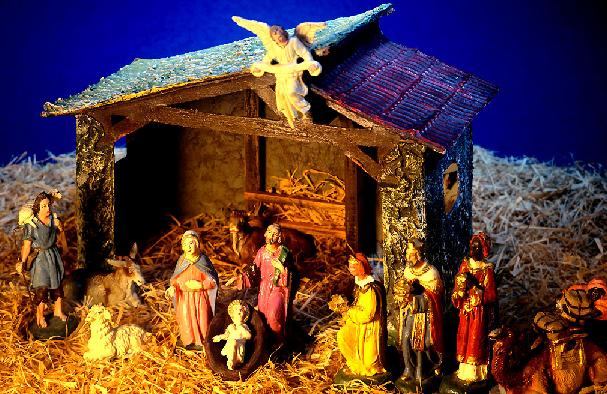

We’ve seen it in a gazillion crèches and umpty-gazillion Christmas cards: an open-sided stable, remarkably sanitary – not a cow patty or pile of donkey dumplings in sight. Towards the centre is a little family of three, radiating internal light, especially the baby in a crate filled with (remarkably sanitary) straw. To one side are three richly brocaded gentlemen with turbans and beards, lugging what look like fancy boxes of chocolates; to the other, shepherds in nightgowns and headcloths are holding long crooks and optional lambs. Donkeys, cows, sheep and camels look on with mild astonishment. Hovering above the stable are two or three winged angels and a huge stylized star.

This iconic scene is a harmonized vision of the nativity of Jesus, bringing together elements from two separate and mutually inconsistent accounts. The Wise Men, star, and fancy prezzies are from the Gospel of Matthew; the angels, shepherds, manger, even the implied setting in a stable, are from the Gospel of Luke. Those of us who find harmonization to be an entertainingly desperate form of special pleading may be suspicious about these inconsistencies, even if they do fit together so prettily on Christmas cards. We might also question how well these narratives, separately and together, fit with real-world issues like history, chronology, astronomy, and biology.

Jonathan Pearce takes up these areas of suspicion in his most recent book, The Nativity: A Critical Examination (Onus Books, 2012), a short but handy summation of awkward questions and inconvenient facts. When did the Nativity take place? In the reign of Herod the Great, or the governorship of Quirinius? Where did Joseph and Mary originate? Nazareth or Bethlehem? Where did they go after the birth? Egypt or the Temple? And how about that census-cum-entirely-gratuitous-mass-migration? Or the geosynchronous star? Or the otherwise undocumented slaughter of the innocents? Or the whole virgin birth thing?

Parce kicks off with a nice excursus on critical thinking, which serves to set up his ground rules for approaching the evidence. The remainder of the book is a series of concise chapters on individual problems with the birth narratives, breaking down a set of complex arguments into digestible chunks. In doing so, he weaves together research done by such scholars as Raymond Brown, Richard Carrier, Bart Ehrman, and many others, providing a good set of references for backup and further reading.

A plausible scenario emerges: that “Matthew” and “Luke” each independently picked up the Markan ball and ran with it in different directions, each producing a midrash aimed at a different fan base. Problems arose only when early Christian communities got together and began to compare notes – and the problems are still there.

Altogether, Pearce’s book is a useful, entertainingly written précis of the two narratives, their irreconcilable differences, and the dogged efforts of gospel apologists to hammer them into shape and give them a historicity that remains entirely spurious. Buy two – one for yourself, and one for a stocking filler. Remember, there are only three hundred and forty-two shopping days before Christmas.