The Founding Fathers are still on the front line of debate amongst atheists and Christians, secularists and theocrats alike. All these years later there is still confusion abounding. Part of the reason why is that there are many misquotes (and this can happen on both sides). Here, for example, is a quote (a letter from Adams to Jefferson) sometimes used by secularists:

This would be the best of all possible worlds if there were no religion in it!!!

The full quote is somewhat different in context and meaning:

Twenty times in the course of my late reading have I been on the point of breaking out, “This would be the best of all possible worlds, if there were no religion in it!!!” But in this exclamation I would have been as fanatical as Bryant or Cleverly. Without religion this world would be something not fit to be mentioned in polite company, I mean hell.

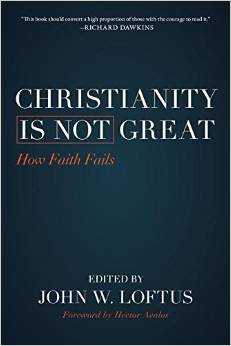

I put that there in the name of balance. However, there is a longer quote that Christians often use which does more damage, and which takes a lot more unpicking. In reading Richard Carrier’s excellent chapter in John Loftus’ superb Christianity is not Great in which I have a chapter myself, there is much to glean about the use of people like Adams and what their actual beliefs and sources were.

I put that there in the name of balance. However, there is a longer quote that Christians often use which does more damage, and which takes a lot more unpicking. In reading Richard Carrier’s excellent chapter in John Loftus’ superb Christianity is not Great in which I have a chapter myself, there is much to glean about the use of people like Adams and what their actual beliefs and sources were.

There is a John Adams quote which is often bastardised and taken out of context (as in here, here, here, and here). Here it is as often quoted by pro-religionists:

“The general principles upon which the Fathers achieved independence were the general principals of Christianity… I will avow that I believed and now believe that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God.”

This is doubly bad because the website I took it from fails to put in one of the sets of ellipses to show omission. It should read (due to being a patchwork of three phrases picked out from a letter to Thomas Jefferson):

The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence, were …

… the general principles of Christianity …

I will avow, that I … believed and now believe that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God….

Why is this important? Well, John Adams was the second US president and was an American lawyer, author, statesman and diplomat, who, as a Founding Father, was a principal leader of American independence from Great Britain. He, as well as many others, are used to define the Constitution upon which rests the foundations of American democracy, held so dear by so many (such that one cannot make an amendment [to an Amendment!] regarding, say, gun law…). Therefore, what these men said is terribly important to arguing for what laws and mission statements the US should have.

So here is that previous quote in full, with emboldened words as Carrier did in his chapter, prevalent to the shifting in meaning that quoting the whole piece forces:

Who composed that army of fine young fellows that was then before my eyes? There were among them Roman Catholics, English Episcopalians, Scotch and American Presbyterians, Methodists, Moravians, Anabaptists, German Lutherans, German Calvinists, Universalists, Arians, Priestleyans, Socinians, Independents, Congregationalists, Horse Protestants, and House Protestants, Deists and Atheists, and Protestants “qui ne croyent rien.” Very few, however, of several of these species; nevertheless, all educated in the general principles of Christianity, and the general principles of English and American liberty.

Could my answer be understood by any candid reader or hearer, to recommend to all the others the general principles, institutions, or systems of education of the Roman Catholics, or those of the Quakers, or those of the Presbyterians, or those of the Methodists, or those of the Moravians, or those of the Universalists, or those of the Philosophers? No. The general principles on which the fathers achieved independence, were the only principles in which that beautiful assembly of young men could unite, and these principles only could be intended by them in their address, or by me in my answer. And what were these general principles? I answer, the general principles of Christianity, in which all those sects were united, and the general principles of English and American liberty, in which all those young men united, and which had united all parties in America, in majorities sufficient to assert and maintain her independence.

Now I will avow, that I then believed and now believe that those general principles of Christianity are as eternal and immutable as the existence and attributes of God; and that those principles of liberty are as unalterable as human nature and our terrestrial, mundane system. I could, therefore, safely say, consistently with all my then and present information, that I believed they would never make discoveries in contradiction to these general principles. In favor of these general principles, in philosophy, religion, and government, I could fill sheets of quotations from Frederic of Prussia, from Hume, Gibbon, Bolingbroke, Rousseau, and Voltaire, as well as Newton and Locke; not to mention thousands of divines and philosophers of inferior fame.

Hopefully you can see the fundamental shift in meaning that is apparent in this larger quote. As Carrier states in his commentary:

Notice what he is actually saying. First, Adams is carefully distinguishing his own personal beliefs from any official state principles. But more importantly, he includes atheists in his list of praiseworthy American freedom fighters, and also says even atheist and anti-Christian philosophers (like Voltaire) were, in his view, advocating for the good principles shared by all Christian sects. In other words, Adams is not saying that American was actually founded on Christian principles in the sense usually meant today; rather, Adams is saying America was founded on universal moral principles shared by all good philosophies, even godless philosophies, Christianity included. He then says that it is his own personal opinion that the Christian God so arranged it But again, he is careful to say that this is his own personal belief, not a state doctrine. [p. 183]

With his own beliefs hinted at here, it is well worth noting that Adams was a Unitarian so his Christian beliefs were very charitable to other worldviews. As Carrier states, he “did not believe in an eternal hell or the divinity of Jesus or even in miracles”. This, then, entirely shifts the paradigm. Those original cobbled-together sentences drawn from three different paragraphs are representative of some serious cherry picking and quote-mining to fulfil the ends: a pro-religionist, pro-Christian governmental system, which is precisely not what John Adams would have wanted (certainly not in the modern way prescribed by many American conservative Christians).