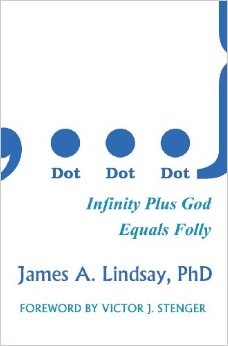

James A Lindsay, whose awesome book Dot, Dot, Dot: Infinity Plus God Equals Folly I edited, recently penned an article with PEter Boghossian and the late Vic Stenger, which has just been released by Scientific American. The article is called “Physicists Are Philosophers, Too”.

Here is an excerpt:

In April 2012 theoretical physicist, cosmologist and best-selling author Lawrence Krauss was pressed hard in an interview with Ross Andersen for The Atlantic titled “Has Physics Made Philosophy and Religion Obsolete?” Krauss’s response to this question dismayed philosophers because he remarked, “philosophy used to be a field that had content,” to which he later added,

“Philosophy is a field that, unfortunately, reminds me of that old Woody Allen joke, “those that can’t do, teach, and those that can’t teach, teach gym.” And the worst part of philosophy is the philosophy of science; the only people, as far as I can tell, that read work by philosophers of science are other philosophers of science. It has no impact on physics whatsoever, and I doubt that other philosophers read it because it’s fairly technical. And so it’s really hard to understand what justifies it. And so I’d say that this tension occurs because people in philosophy feel threatened—and they have every right to feel threatened, because science progresses and philosophy doesn’t.”

Later that year Krauss had a friendly discussion with philosopher Julian Baggini in The Observer, an online magazine from The Guardian. Although showing great respect for science and agreeing with Krauss and most other physicists and cosmologists that there isn’t “more stuff in the universe than the stuff of physical science,” Baggini complained that Krauss seems to share “some of science’s imperialist ambitions.” Baggini voices the common opinion that “there are some issues of human existence that just aren’t scientific. I cannot see how mere facts could ever settle the issue of what is morally right or wrong, for example.”

Krauss does not see it quite that way. Rather he distinguishes between “questions that are answerable and those that are not,” and the answerable ones mostly fall into the “domain of empirical knowledge, aka science.” As for moral questions, Krauss claims that they only be answered by “reason…based on empirical evidence.” Baggini cannot see how any “factual discovery could ever settle a question of right and wrong.”

Nevertheless, Krauss expresses sympathy with Baggini’s position, saying, “I do think philosophical discussion can inform decision-making in many important ways—by allowing reflections on facts, but that ultimately the only source of facts is via empirical exploration.”

The article goes on to talk about models of reality and whether physicists are using platonic realism to account for their models. This is an area which I often bang on about: abstract ideas. The article states as conclusion:

So, although the prominent physicists we have mentioned, and the others who inhabit the same camp, are right to disparage cosmological metaphysics, we feel they are dead wrong if they think they have completely divorced themselves from philosophy. First, as already emphasized, those who promote the reality of the mathematical objects of their models are dabbling in platonic metaphysics whether they know it or not. Second, those who have not adopted platonism outright still apply epistemological thinking in their pronouncements when they assert that observation is our only source of knowledge.

Hawking and Mlodinow clearly reject platonism when they say, “There is no picture- or theory-independent concept of reality.” Instead, they endorse a philosophical doctrine they call model-dependent realism, which is “the idea that a physical theory or world picture is a model (generally of a mathematical nature) and a set of rules that connect the elements of the model to observations.” But they make it clear that “it is pointless to ask whether a model is real, only whether it agrees with observations.”

We are not sure how model-dependent realism differs from instrumentalism. In both cases physicists concern themselves only with observations and, although they do not deny that they are the consequence of some ultimate reality, they do not insist that the models describing those observations correspond exactly to that reality. In any case, Hawking and Mlodinow are acting as philosophers—epistemologists at the minimum—by discussing what we can know about ultimate reality, even if their answer is “nothing.”

All of the prominent critics of philosophy whose views we have discussed think very deeply about the source of human knowledge. That is, they are all epistemologists. The best they can say is they know more about science than (most) professional philosophers and rely on observation and experiment rather than pure thought—not that they aren’t philosophizing. Certainly, then, philosophy is not dead. That designation is more aptly applied to pure-thought variants like those that comprise cosmological metaphysics.

Well worth a read.