I was recently having a debate on You Tube, of all places, with a UKIP supporter who refused to take on board any of my points unless the solutions I provided were free market centred. A selection of his comments will follow, this first one was after I pointed out that UKIP are science deniers (and I won’t post you the full nonsense he replied on his attempted philosophy of science, eg “People who use the word “consensus” in science can f*ck off out of science. That is a socialist/collectivist idea.”):

Also, could you point me to the political party that has a renewable energy solution and is free-market? In fact, could you point me to a political party anywhere on earth that is free-market and has a solution to the energy crisis which is also renewable? No? Well then bugger off. Socialism was sooooo last century.

and

I want to vote for a political party that is free-market. There are plenty of arguments out there for it. I don’t like socialism and I don’t want it, and I don’t want keynesian economics and I don’t want Tony Blair-style third-way economics. I want the free-market and that is what I am going to vote for. What is your solution to the energy crisis and can you direct me to the party that offers a competitive solution, but is also free-market? No? Well then bugger off I’m voting UKIP.

and

“Tell me, how does the free market pay for negative externalities,” The free-market makes sure that oddjob collectivist control-freaks cannot tell you or I what we should or should not buy, and to buy at whatever price we choose and not they. It means that socialist control freaks cannot force you to buy things you don’t need or restrict things that you might want to see, read, eat or use. It also means you have very little taxes, and makes everyone wealthier, including the poor.

He either didn’t understand what negative externalities were or was hopelessly avoiding the question.

So the key line, for me, was the last one there, tat free market economics with its low taxes makes everyone wealthier, including the poor in some kind of trickle down economics.

Because it appears to be utter rubbish.

A paper by economists Facundo Alvaredo, Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty, and Emmanuel Saez lays out just how good the US is at income inequality. It is top of the developed world pile.

As the HuffPo reports:

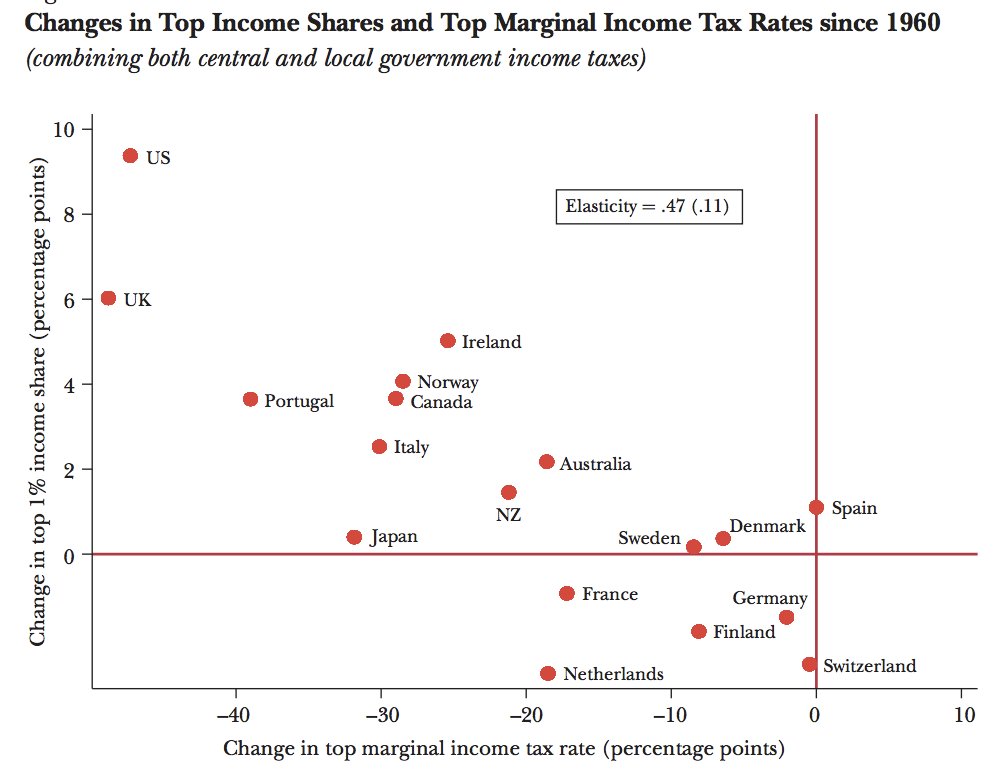

Since the 1970s, the top 1 percent of earners in the U.S. has roughly doubled its share of the total American income pie to nearly 20 percent from about 10 percent, according to the paper. This gain is easily the biggest among other developed countries, the researchers note. You can see this in the chart below, taken from the paper, which maps the income gains of the top 1 percent in several countries against the massive tax breaks most of them have gotten in the past several decades. (Story continues after chart.)

The higher the dot, the more income inequality has grown in that country. See the red dot waaaay up in the left-hand corner, far away from everybody else? That is the United States, where the top earners have made more while getting their taxes slashed by over 40 percent.

This echoes an OECD study from earlier this year that found the U.S. had the highest income inequality in the developed world. It followed only Chile, Mexico and Turkey among all nations.

That OECD report makes for interesting reading. The Atlantic reports on this:

A new OECD report concludes that income inequality is rising in most developed countries. Here’s the OECD’s graph of Gini coefficients by country. Gini coefficients can theoretically range from 0.0 to 1.0, with higher values indicating greater inequality.

The relative rankings of inequality haven’t changed much over two decades, with the United States leading the trend. But inequality is rising in most developed countries, literally upending the Kuznets curve – one of market fundamentalists’ most cherished ideas.

The Kuznets Curve, named after Nobel Laureate Simon Kuznets, predicts that as nations become wealthier, inequality initially rises and then declines, like a single squeeze of an accordion. Economists hypothesized inequality would rise as workers transitioned from low-paying agricultural work to higher-pay industrial work, but that the lower classes would catch up once the industrial revolution completed. Kuznets himself thought that as a country grew wealthier, it would also implement more redistributive policy. Kuznets, who died in 1985, was more or less right, but only for his lifetime.

Recently, in the last few decades, income inequality has been on the rise again. The Atlantic continues:

Though the report never puts it this way, one interpretation of the data is that inequality naturally grows from unfettered capitalism. Marxists won’t be surprised, but the report should be disturbing for centrists who believe both in free markets and social equality. If free-market capitalism works so well for every income level, why have so many people seen income pass them by with capitalism working more efficiently than ever before?

One possible problem is the moral foundation that underlies capitalism: meritocracy. Our faith in meritocracy is deeply held and hardly questioned. After all, rewarding people according to merit is superior to corruption or nepotism.

But a system superior to corruption and nepotism is not necessarily the best possible system. What we consider “merit” is the result of education, and greater education requires greater income. Meritocracy, therefore, is a kind a social divider. As I wrote earlier, the idea of the “self-made person” is at odds with its moral connotations.

Until we come up with a better system, the best solution is in the OECD’s conclusion: “Policies that promote the up-skilling of the workforce are therefore key factors to reverse the trend to further growing inequality.” The only way to achieve fairness in a meritocracy is to provide more equal opportunities for everyone to attain merit.

So it appears that the US, with its belief in unfettered free market capitalism is on a highway to continued inequality. People need to remember what went on in Victorian Britain until regulation came along, until the Factories Act, the Agricultural Gangs Act and so on. Child labour was a result of such free market ideals (as Chang who I later quote states, “If some markets look free, it is only because we so totally accept the regulations that are propping them up that they become invisible”). Moreover, for example, I heard the other day that the gap between blacks and whites in the US is now greater than between blacks and whites in apartheid South Africa! Wow.

For every dollar in assets owned by whites in the United States, blacks own less than a nickel, a racial divide that is wider than South Africa’s at any point during the apartheid era.

The median net worth for black households is $4,955, or about 4.5 percent of whites’ median household wealth, which was $110, 729 in 2010, according to Census data. Racial inequality in apartheid South Africa reached its zenith in 1970 when black households’ median net worth represented 6.8 percent of whites’, according to an analysis of government data by Sampie Terreblanche, professor emeritus of economics at Stellenbosch University. [source]

(It’s worth noting that US blacks are a smaller proportional part of the overall population, so this skews the issue. Nevertheless, the point is salient).

Not only does the environment appear to suffer with lack of regulation because such free market economics does not account for negative externalities. For those who have not come across the term:

A negative externality (also called “external cost” or “external diseconomy”) is an economic activity that imposes a negative effect on an unrelated third party. It can arise either during the production or the consumption of a good or service.[4]Barry Commoner commented on the costs of externalities:

- Clearly, we have compiled a record of serious failures in recent technological encounters with the environment. In each case, the new technology was brought into use before the ultimate hazards were known. We have been quick to reap the benefits and slow to comprehend the costs (Quoted from [5]).

Many negative externalities are related to the environmental consequences of production and use. The article on environmental economics also addresses externalities and how they may be addressed in the context of environmental issues.

With such capitalism, third parties such as tax payers, or indigenous populations of areas where corporations are extracting natural resources or polluting, have to pay the costs of those products, where the corporations reap the rewards, without taking on the costs of their endeavours.

But that is a side issue. The main thrust is that poor people in the most free market of economies appear to stay poor whilst the rich get even richer.

And no amount of You Tube assertion changes that fact.

Such a belief that giving tax breaks to corporates, less government and minimising welfare is summed up as trickle-down economics. Let the rich get lots of money and this trickles downwards the poor and closes the gap (or horse and sparrow: give the horse enough oats and it’ll shit some out on the road for sparrows to peck at). As Damien O’Connor, Labour MP in New Zealand stated, it is “the rich pissing on the poor”.

Cambridge professor Hajoon Chang has written about this, such as in a book on the subject, and has criticised the policies of trickle down advocates citing examples of slowing growth in the last few decades, rising income inequality in most rich nations, and the effectiveness of welfare provision in raising living standards across all income brackets rather than at the top only. As he states:

Thus seen, opposing a new regulation is saying that the status quo, however unjust from some people’s point of view, should not be changed. Saying that an existing regulation should be abolished is saying that the domain of the market should be expanded, which means that those who have money should be given more power in that area, as the market is run on one-dollar-one-vote principle.

So, when free-market economists say that a certain regulation should not be introduced because it would restrict the ‘freedom’ of a certain market, they are merely expressing a political opinion that they reject the rights that are to be defended by the proposed law. Their ideological cloak is to pretend that their politics is not really political, but rather is an objective economic truth, while other people’s politics is political. However, they are as politically motivated as their opponents.

Breaking away from the illusion of market objectivity is the first step towards understanding capitalism.

What seems to be very worrying is a 2012 report (wiki):

A 2012 study by the Tax Justice Network indicates that wealth of the super-rich does not trickle down to improve the economy, but tends to be amassed and sheltered in tax havens with a negative effect on the tax bases of the home economy. – Heather Stewart (July 21, 2012). “Wealth doesn’t trickle down – it just floods offshore, research reveals”. The Guardian. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

The end result from al of these amassed quotes is that free market economics in it purest form, with tax cuts to the rich, should be opposed as contriubting to widening the gap between rich and poor, fortunate and less fortunate.