Today was Martin Luther King Jr day here is the US. Rev. MLK, revered as the spearhead of the civil rights movements and the fight against segregation, is often held up as an example of the positive impact religion can have on politics. For example, the 2010 PBS documentary “God in America“, true to media form, paints a very positive picture of the role of religion in organizing the activists, and helping them through the difficulties of their struggle. Likewise, a not-so-brilliant piece in Huffington Post (about a year old now) had this to say on the subject:

In the South in the ’50s and ’60s, it was through the incredible network of black churches in African-American communities that activists were able to organize and share information, and ultimately achieve to the unprecedented successes of Civil Rights. These communities empowered their members, yet atheists construct a presumption that these communities must be in need of empowerment. It seems to be borne from a fear of all things associated with religion: a given atheist is often known to talk about fighting “religion” rather than “dogmatism” or “supernaturalism”, as if “religion” were a wholly poisonous monolith.

Aside from the straw man attack on New Atheism, the piece summarizes the orthodox narrative on the civil rights movement: it was through religious involvement that the Civil Rights Movement came to succeed, etc, etc.

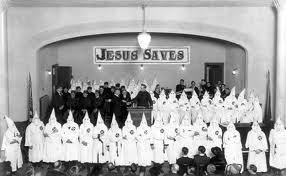

A closer look at the history, however, shows two problems with this concept: 1) To a great extent, religion was complicit in the institutional racism that had to be confronted by Civil Rights activists in the first place, and 2) While the part played by churches in organizing activism, it doesn’t follow that the Civil Rights movement owed its existence to churches; in fact, both the philosophy and the organization was carried out to a great extent by secularists.

Let’s examine the first point now.

Despite his faith and his frequent use of religious language, MLK knew better than most that religion was not always on his side; often it was indifferent to the suffering of his people, or in the worst case, actively undercutting his efforts. Look, for example, at the following quotes from his famous letter from the Birmingham jail, to his fellow clergy:

I have been so greatly disappointed with the white church and its leadership.

I have heard numerous southern religious leaders admonish their worshipers to comply with a desegregation decision because it is the law, but I have longed to hear white ministers declare: “Follow this decree because integration is morally right and because the Negro is your brother.” In the midst of blatant injustices inflicted upon the Negro, I have watched white churchmen stand on the sideline and mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities. In the midst of a mighty struggle to rid our nation of racial and economic injustice, I have heard many ministers say: “Those are social issues, with which the gospel has no real concern.” And I have watched many churches commit themselves to a completely other worldly religion which makes a strange, un-Biblical distinction between body and soul, between the sacred and the secular.

I have traveled the length and breadth of Alabama, Mississippi and all the other southern states. On sweltering summer days and crisp autumn mornings I have looked at the South’s beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: “What kind of people worship here? Who is their God? Where were their voices when the lips of Governor Barnett dripped with words of interposition and nullification? Where were they when Governor Wallace gave a clarion call for defiance and hatred? Where were their voices of support when bruised and weary Negro men and women decided to rise from the dark dungeons of complacency to the bright hills of creative protest?”

MLK was, of course, talking about southern governors’ call on their constituents to defy the Supreme Court Desegregation Decision of 1954.

MLK is also known for this famous statement: “Sunday morning is the most segregated hour of Christian America.” Indeed, centuries of Christianity had not lead to an end of segregation by itself; and without activists like MLK, it never would.

And there is another one of those activists like MLK, who has fallen into obscurity despite his crucial role in the movement.

It has been 50 years since an estimated 250,000 people converged on the capital for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. With each passing year, the story of that day becomes the story of Martin Luther King Jr. and his iconic speech.

If you have any doubts that this is what time has done with Aug. 28, 1963, look no further than what Time, the magazine, has done to commemorate the 50th anniversary of that day.

Open the magazine and flip past some black-and-white photos of the scene on the mall to a color photo, a posed shot after the march, the Oval Office. President John F. Kennedy is standing in the middle of the men who led the march. King is in the front row, with several feet and two people between him and the president.

The caption says: “King and his lieutenants meet with Kennedy …”

The people in the photo would have chuckled at such a description — King and his lieutenants? — not because they didn’t admire King, but because there was one man who clearly had led them to this moment. One man whom they considered The Founding Father of the civil rights movement. One man who for more than two decades had been dreaming of such a march on Washington.

It wasn’t King. It was the 74-year-old man standing next to Kennedy.

Asa Philip Randolph.

And who was A Philip Randolph?

Of the 17 speakers listed on the march program that day, only John Lewis, then a 23-year-old student leader, is still alive. He now is a 13-term congressman from Georgia. Reached at his office in Atlanta, he brought up the photo op in the Oval Office before being asked about it. He said he has photos from that moment, on the wall and on his desk, in his Washington office. And he mentioned where “Mr. Randolph” — to this day, that’s what Lewis calls him — was standing. Right next to the president.

“I’ve always said — and it’s not to take away from the role of Dr. King or anyone else — but without A. Philip Randolph, there wouldn’t have been a March on Washington,” Lewis said. “People should never, ever forget the role that A. Philip Randolph played. He should be looked at as one of the founding fathers of a new America, a better America.”

Kennedy invited several civil rights leaders to Washington for a meeting on June 22, 1963.

It was in this meeting — a little more than two months before the actual march — that one man in the room did more than bring up the idea of hundreds of thousands of people converging on the nation’s capital. Randolph told the president it was going to happen.

When Lewis recalls this moment, he doesn’t just repeat Randolph’s words. He mimicks his voice.

“He said in his baritone voice — I can get it down just like he said it,” Lewis said, taking his own already deep voice and lowering it. “Mr. President, the black masses are restless and we’re going to march on Washington.”

He recalls that Kennedy, caught off guard by this, started “moving and twisting” in his chair before saying, “Mr. Randolph, if you bring all these people to Washington, won’t there be violence and chaos and disorder?” The president said he worried a march could backfire, derailing hopes of getting a civil rights bill through Congress.

Going back to Randolph’s baritone, Lewis recalled the matter-of-fact response: “Mr. Randolph said, ‘Mr. President, this will be an orderly, peaceful, non-violent protest.’ ”

One month later, in July 1963, six civil rights leaders gathered at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York. King, Randolph, Lewis, Whitney Young, James Farmer and Roy Wilkins were dubbed “The Big Six.” But Norman Hill, the staff coordinator for the march who is now 80, recalled in a phone interview from his Washington office that one man was responsible not just for bringing the six of them together, but for bringing civil rights to that point.

“A. Philip Randolph rightfully and accurately should be called the father of the modern civil rights movement,” he said.

Without him, maybe that meeting doesn’t even happen. With him, it not only happened, the six men — each strong-willed, with varied ideas about what they wanted and how to go about achieving it — managed to work together and agree on a plan for Aug. 28, 1963. They started by picking an official leader, one man who would be the director of the march. A man who wasn’t named King, but was named Asa after an Old Testament king.

Despite having a biblical name, Randolph-unlike MLK-was not religious at all. In fact he was the antithesis of religious: he went on to become the Humanist of the Year in 1970.

And so, if PBS, Huffington Post, Time, etc continue to give religion all the credit and none of the criticism (as we have come to expect of the media), I hope you, dear reader of this blog, will recognize that the story is far more complex than the Civil Rights movements owing its existence to religion.