No well-documented source exists which investigates the topic of Victorian post-mortem photography. Snopes.com has no entry, so let’s do this one Snopes-style.

CLAIM: Victorian era (1840s-1900) families often took photos of dead loved ones posed to look alive, sometimes next to them and/or standing thanks to the use of support stands and straps. Variants include the painting of eyelids to appear open, hidden mothers holding dead children, the dead made to appear to stand

Status: MOSTLY FALSE

WHAT’S TRUE: Victorians did photograph their recently deceased loved ones1-5. Photographers often tried to create portraits of the dead. Images to represent who they were alive, not dead, and so tried to make them appear alive. Some, especially children, were made to appear to be sleeping. Others were sat up, sometimes with eyes open. Some feature parents cradling their infant. Later images are clearly funerary, with the subject surrounded by flowers or in a coffin.

Paul Frecker London is a reputable dealer of Victorian post-mortem (PM) photographs and daguerreotypes. Visit their online gallery to see what real PM portraits typically look like. These documented images were published in the Journal of Photography5.

WHAT’S FALSE: Numerous photos claimed to be of deceased people were alive when the photo was taken. Un/blurred faces, the presence of a posing stand, “rigid” postures, and vacant stares said to indicate death or life are unreliable or fictional. Posing stands were never used to make corpses into mannequins. There are no pictures in which a dead person is standing and appears alive. During most of the Victorian period, photographs were not so prohibitively expensive that most people could only afford them once in a lifetime. Most offending sites are a mix of real and mistaken or fake PM images.

EXAMPLE: [Collected from the internet. June, 2016. More examples below.]

ORIGIN: Art and culture historians have described Victorian post-mortem photography since at least the 1980’s1 2. Before that, death photography was thought to be too morbid a topic, even by social scientists who wrote about the denial of death in 20th century America. In Secure the Shadow, scholar Jay Ruby wrote,

In spite of the increase in popular and scholarly work and the shift in public attitudes, the place of photography in our dealings with death has been virtually ignored by art historians, by those concerned with the material culture of death, and even by professionals in the field of grief counseling. Studies of images of death such as those of Aries (1985), Lloyd (1980), Pigler (1956), and Llewellyn (1991) do not mention the practice. (p.8)

The general public remained unaware of these academic and photojournal publications. Private collections of Victorian death and mourning photographs may have set the stage for mythification. The Thanatos Archive catalogs 2000 “death” portraits. Thanatos has made its images accessible online since 2002 (for a subscription fee). The Burns Archive boasts a million images, but only some are death-related. The Burns Archive was founded by ophthalmologist Dr. Stanley B. Burns. These and other collections made Victorian post-mortem and pre-mortem photos available to lay internet audiences.

The first appearance of definitely-not PM photos being billed as such appeared online in 2004. At least, that’s as far back as the archive goes. Although it is the website of Arizona State University’s School of Arts, the page is nothing but an array of some 42 images. Many are misidentified as PM. For example:

These photos appeared, but failed to gain traction until around 2008 when the story was picked up by larger sites like ScienceBlogs and mental_floss. By 2009, the familiar tropes of the myth have been stated plainly in a variety of places. The Ashford Zone blog said that you can tell death by blurred eyes and the visibility of a posing stand.

Google trends indicates that the myth comes to full power at the end of 2014. Around this time the website Viralnova featured many misidentified Victorian photos and repeats all of the falsehoods about Victorian death photography. At almost the same time, The Thanatos Archive published some of its material in the book Beyond the Dark Veil: Post Mortem & Mourning Photography from The Thanatos Archive. Similar books like The Victorian Book of the Dead and Memento Mori were published within a few months of each other.

As of now, the false PM photos and myths have been republished on thousands of blogs, news sites, Pinterest pages, YouTube channels, Facebook pages, twitter, Reddit, and photo sites like flickr.

Posing stands

Posing stands

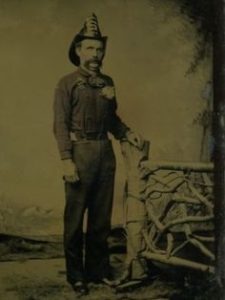

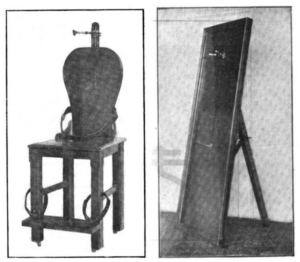

Posing stands were used to help keep subjects steady. They were never used on the dead. Indeed, they could not be. Look at this image to the right. This grown man could not be supported with a small stand unless it was made of adamantium. He is holding his head up, and looking at the camera. His shoulders and hips are squared, not slumped. His hat points perfectly up, because his entire body posture is living-human normal. If some photographer accomplished this with a small stand, they must be an engineering wizard.

Historian R.J. Noye explained these stands (head rests) with lovely photos and illustrations here. Noye wrote,

The use of the headrest dates back to the earliest years of photography, and when commenting on the fact that Daguerre believed that portraits by his daguerreotype process were not possible due to the long exposures required the Athenaeum (August 1839) suggested that ‘the head could be fixed by means of supporting apparatus.’

Ruby mentioned restraints as well2 (p.90), but referred to living subjects. This passage also partly explains why many Victorians photographed had a rigid posture, wrongly said to indicate death in many instances:

In the photographic studio of the 1840s through the 1860s, people were placed in restraints – clamps that prevented any head movement. They were told to sit perfectly still, not even to blink. The result was an image of a person without facial emotion holding a rigid, expressionless posture.

The Standing Dead

The exception sometimes proves the rule. The dead were sometimes made to stand and to look alive and conscious. However, this was done by forensic photographers, not memorial portrait makers. In The Victorian Book of the Dead (and a summarized blog post), Chris Woodyard explained that pre-photography, many corpses went unidentified due to the disfigurement of death. Forensic photographers at the very end of the Victorian Era attempted to restore partly decomposed bodies and then photograph them standing or sitting. This is the furniture required to do it:

Romanian doctor Nicolas Minovici was famous for innovating methods of restoring corpses for identification. Minovici replaced eyes with artificial appliances rather than painting the lids or retouching. He used small pins to fix the face into various expressions. Find page 857 in the Archives to see how effective this was – be warned, these are graphic and disturbing photos. Ironically, had Victorians used Minovici’s methods, their post-mortem portrait subjects could have been smiling and looking more animate than those of many living Victorians.

Blurred eyes or faces and rigid postures

Many factors affect the quality of a photo. The level and color of lighting, tiny movements of each person, tiny movements of the camera. In the non-digital non-instant age, occasional blur was inevitable. Clarity doesn’t mean death. This photo of Thomas Edison was taken in 1888. Note the crisp detail, and alived-ness.

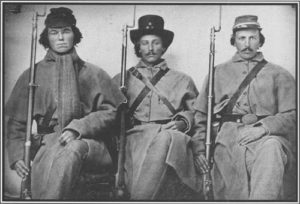

Conversely, here are Civil War soldiers. Note the “vacant” stares, glazed eyes, and rigid postures. They are sitting perfectly straight, heads up, looking at camera, and each gently holding their rifles. These are not dead men (at the time).

Historical accounts

I will briefly review accounts and views of Victorian PM photography from cultural historian Dan Meinwald, historical scholar Jay Ruby, art historians Patrizia Munforte and R. J. Noye, photographer, writer, and curator Robert Hirsch, and photography historian Audrey Linkman. None ever mention corpses made to stand up. None mention the use of poser stands, except on the living. While all provide example photographs, none use PM photographs found in popular blog posts and media accounts that I have described as misidentified PM pictures. Indeed, Patrizia Munforte debunked convincing portraits of the supposedly dead in her dissertation.

These scholarly sources notwithstanding, exactly two references to possible authentic creepy standing death photos are known6 (found by Woodyard). The photos themselves are lost to history.

An Irish family, living in the southern part of the city, called on me about two years ago to take a picture of their dead son—a young man—with his high hat on. It was necessary to take the stiffened corpse out of the ice-box and prop him up against the wall. The effect was ghastly, but the family were delighted, and thought the hat lent a life-like effect. Photographic Times and American Photographer, Volume 12, J. Traill Taylor, Editor, 1882

I was tenting in an Arizona town and quite a number of Mexican children died. These people are quite fond of pictures, and seem to like corpse ones if they have none taken in life. Most of them in the town I was in preferred having them standing, so I ordered them to place the corpse against the back of a chair and tie it thus outside of their doby house in the sun; and I will say that a standing corpse picture looks much better than one lying down. “Nine Years a Tent Photographer,” E.A. Bonine, Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, 1898.

— Dan Meinwald —

Meinwald wrote the essay and book Memento Mori. You can read the fascinating essay online at UCLA.edu. Part 2 deals with this subject matter most directly. It is inconsistent with mythic PM accounts.

— Jay Ruby —

In Post-Mortem portraiture in America, Jay Ruby detailed methods and techniques used from the pre-photographic era to the 20th century. The paper included 26 images exemplifying sorts of post-mortem imaging and photography. It even included advice from professional photographers on how to photograph the dead. None of these included posing the dead to appear standing or in a “just hanging out” pose. The death bed repose was sometimes popular. When family were included, it was sometimes to create a scene or vignette depicting grief at or near the time of death. Photographer J. Southworth advised a panel on technique (1873):

When I began to take pictures, twenty or thirty years ago, I had to make pictures of the dead. We had to go out then more than we do now, and this is a matter that is not easy to manage; but if you work carefully over the various difficulties you will learn very soon how to take pictures of dead bodies, arranging them just as you please … The way I did was just to have them dressed and laid on the sofa. Just lay them down as if they were in a sleep.

Ruby’s book Secure the Shadow: Death and photography in America expands on the paper. Another post-mortem photographer’s advice, Charlie E. Orr, from an 1877 edition of The Philadelphia Photographer described his technique:

Place the body on a lounge or sofa, have the friends dress the head and shoulders as near as in life as possible, then politely request them to leave the room to you and your aides, that you may not feel the embarrassment incumbent should they witness some little mishap liable to befall the occasion. If the room be in the northeast or northwest corner of the house, you can almost always have a window at the right and left of a corner. Granting the case to be such, roll the lounge or sofa containing the body as near into the corner as possible, raise it to a sitting position, and bolster firmly, using for a background a drab shawl or some material suited to the position, circumstance, etc. Having posed the model, we will proceed to the lighting.

This is all that Orr mentioned about positioning the body (p.57-8). There is not a word about stands, braces, corpses made to stand, or elaborate measures to arrange limbs.

Even these techniques practiced by those photographers, were rarely used by any others:

And yet, Southworth’s description of techniques for composing a deceased subject, cited above, seems to have had little effect on the rest of the profession. Figure 17 clearly shows that Southworth practiced what he preached. But it is a most unusual postmortem photograph. Remarkably few postmortem photographs display this skill for composing the body. The majority are simple likenesses. They record the features of the deceased and nothing more.

Ruby described the 3 stylistic forms seen in 19th-20th century post-mortem photography:

From 1840 until 1880, three styles of postmortem photography emerged. Two types were designed to ‘deny death,’ that is, to imply that the deceased was not dead, while a third variant portrays the deceased with mourners. (p.63)

The three styles are the final repose, the dead posed to appear asleep and usually in a bed or crib; “dead, but alive” to use Munforte’s phrasing, where the dead may be upright with eyes open or closed, but not in any casual or “just hanging around” tone; and lastly, the mourning scenes, in which the family may appear with the dead on their deathbed, funeral, or even graveyard.

— R. J. Noye —

Noye focused much more on the craft and technical aspects of Victorian photography. Yet, his account does not support the mythic claims that now circle the internet every month or two.

— Patrizia Munforte —

Subscribers to the Thanatos Archive discuss and debate whether particular Victorian photos are truly PM or not based on analysis of the photos4. Munforte emphasized that the constructed meaning of a portrait is more important than the state of the subject or forensic analysis by contemporary morbid gawkers. She endorsed Ruby’s view of the three modes of Victorian PM photography and then analyzed and deconstructed “clear” cases of PM. She showed that even these can be misinterpreted and misunderstood:

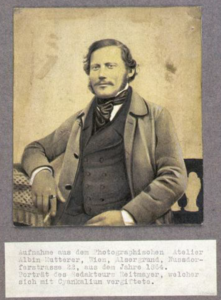

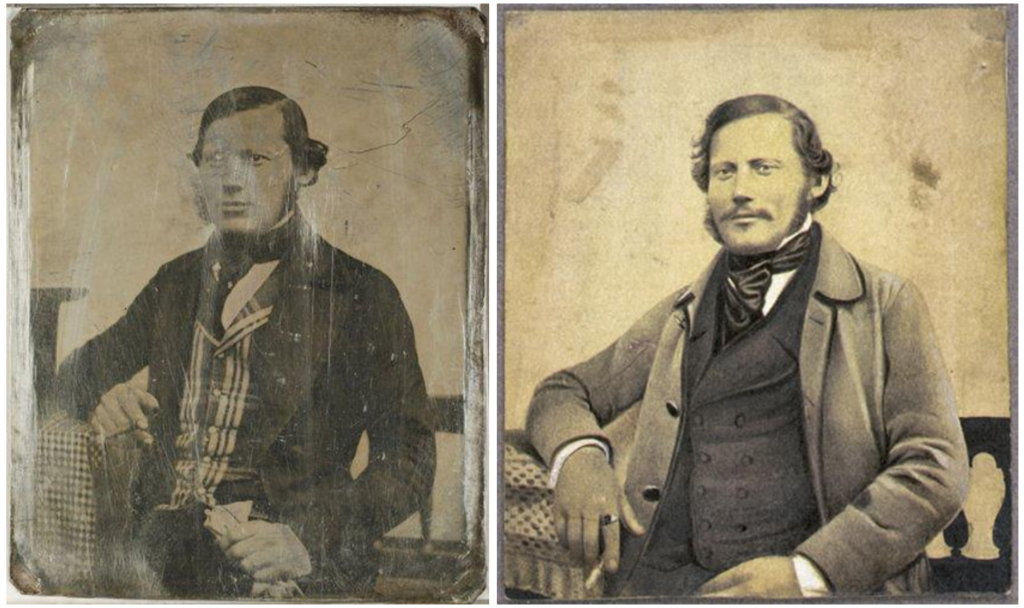

My approach compared two portraits of Reitmayer made twenty years apart. In doing so, I was able to clarify that the 1864 photograph of the apparently deceased Reitmayer was a new print of an earlier portrait from the 1840s. …A death portrait is not necessarily a portrait of a corpse; as the case studies demonstrated, it can be a far more complex, multilayered image which presents the deceased not only through an appearance of life and resemblance of the sitter but also through the material, haptic quality and photographic techniques. [See more on the Reitmayer case below -Ed]

— Robert Hirsch —

Hirsch is the author of Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. The 500 page text spends a good deal of paper on the Victorian era, but only a few hundred words on death and mourning. Which is odd considering how often Hirsch is cited by fake PM sites. He wrote nothing that supports fanciful interpretations of Victorian photos.

— Audrey Linkman —

Linkman wrote a paper on the even more-Victorian Victorians, th e British5. This is another paper focusing on the methods and means primarily of post-mortem photography, but also commenting on social attitudes. She often compares American and British (and other European) Victorians. However, like all the other scholars, she never mentioned standing-up of the dead, the use of stands and wires for posing, painting on eyelids, et cetera.

e British5. This is another paper focusing on the methods and means primarily of post-mortem photography, but also commenting on social attitudes. She often compares American and British (and other European) Victorians. However, like all the other scholars, she never mentioned standing-up of the dead, the use of stands and wires for posing, painting on eyelids, et cetera.

Fake post-mortem photos are big business

Non-PM and photos of unknowable subjects are sold on eBay. For just $165 you could buy this photo of a man holding his child. On Amazon you can buy book versions of PM blog posts, complete with rehashes of the same erroneous claims.

Woefully misidentified PM photos

Reitmayer committed suicide in 1864. His body was taken to PM photographer Albin Mutterer, renowned for his talent at making striking “alive, but dead” portraits. The captions on the salt paper print indicate that the photo was taken after his death. This seems like a clear-cut case of PM photography. Even experts believed that it was, including art historians Felix Hoffman and Steffen Siegel. Patrizia Munforte dug deeper.

Mutterer was talented indeed. Munforte determined that he manipulated a twenty-year-old daguerreotype to construct an apparently new image to serve as a memorial photo. He mirrored it to flip the left/right because older daguerreotypes were typically mirror-flipped; photographs were not. He retouched the face so that it looked older. Here is the mirrored original next to Mutterer’s portrait. Note the identical hairlines, but that the body and head are slightly out of proportion.

The image was created after Reitmayer’s death, but no corpse was involved. Seeing is not believing, even in 1864.

Websites perpetuating the myth

It is surprising this list includes reputable news outlets and blogs like ScienceBlogs. It is a testament to the compelling allure of the morbid and weird. Most, including the BBC, feature no source citation at all.

BBC.com • The San Francisco Globe • ABC News • Wikipedia • Huffington Post • Buzzfeed • mental_floss • Cracked • ScienceBlogs • Viralnova • io9 • Listverse • Dose.com • DailyMail • mdolla • 9gag • Wimp • LiveLeak

Websites repudiating the myth

Kudos and thanks.

The Skeptics Guide to the Universe podcast (#518, June 2015) nailed it. Well done. See the Special Report segment Memento Mori by Steven Novella.

HauntedOhioBooks.com Excellent debunking by Victorian Book of the Dead author Chris Woodyard

The Myth of the Stand Alone Corpse by Susan Cantrell and her related Pinterest Board. Props to Susan for being among the first to critically respond to the myth. Her work is one of the inspirations of my own investigation.

Fakes & Myths in Victorian Post Mortem Photography Facebook page

Mourning Potraits blog

Daze & Weekes by Ali Weekes Shinall. A humorous and engaging treatment.

Works Cited

[1] Ruby, Jay. 1984. Post-Mortem portraiture in America. History of Photography. Vol 8, no 3. Link.

[2] Ruby, Jay. 1995. Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America. The MIT Press. Link.

[3] Hirsch, Robert. 2008. Seizing the Light: A Social History of Photography. McGraw-Hill Education; 2 ed.

[4] Munforte, Patrizia. 2015. The Body of Ambivalence: The ‘Alive, Yet Dead’ Portrait in the Nineteenth Century. Re·bus. no 7, Summer. Link.

[5] Linkman, Audrey. 2006. Taken from life: Post-mortem portraiture in Britain 1860-1910. History of Photography. Vol 30, no 4. Link.

[6] Woodyard, Chris. 2014. The Victorian Book of the Dead. Kestrel Publications.

EDITED 6/21 to add forensic photography material.