In a plenary address at the Human Behavior and Evolution Society (HBES) conference last week psychologist Brad Duchaine offered a compelling case for facial processing as a discrete cognitive unit in the brain. Many of the evidences he reviewed I had heard before, but they remain striking: people can lose the ability to detect faces, while seeing objects perfectly well and vice-versa. Faces are difficult to recognize when upside-down, while inverted objects are not. In one particularly compelling case a person reported looking at their dog and when they looked up, could see the dog’s face where every person’s face around them should have been.

Yoichi Sugita’s monkey studies seem the most definitive, however. Sugita deprived infant monkeys of faces or even face-like visuals for 6-24 months. In spite of this, the monkeys had no problem recognizing and discriminating human and monkey faces. Sugita also demonstrated that if you expose the infants to only one kind of face stimuli, either human or monkey faces after the period of deprivation the monkeys develop a permanent preference and discriminatory bias for that type. Even after a year, the bias remained, in spite of exposure to both sorts of faces. From this, and other research it seems reasonable to conclude that the basic ability to recognize faces is not expertise or training but an innate feature which apparently acquires the details of the first sorts of faces the individual sees and permanently calibrates based on them. Read the study here: http://www.pnas.org/content/105/1/394.long

The hypothesis that face recognition is an innate module has been a controversial one, part of the more general controversy that there may be many such modules doing important thinkery such as social cognition and reasoning about animals and artifacts. Evolutionary psychology is sometimes denigrated for endorsing “massive modularity”. Now it must be said that different researchers and academics mean different things by “module” and that, to my knowledge, nobody claims that we know the details about how any one module, if it exists, works at the neuronal level. See “further reading” below for links to discussions on this part of the debate. For the purposes of this essay, we’re talking about domain general versus domain specific cognition being responsible for mental capabilities of humans and other animals.

I am not a cognitive or neuro-scientist, but it seems there are no other well-developed or supported theories about how grey goo does cognition. For a good overview and discussion of what modularity means and answers to objections I recommend “Modularity in Cognition: Framing the Debate” by Clark Barrett and Robert Kurzban. They cover objections such as plasticity and apparent domain general human capabilities. Since modularity is still being raised as an objection to the evolutionary psychology paradigm I would like to register some of my thoughts.

The answer seems to be “No”

Is there a cogent alternative hypothesis to modularity vis-à-vis the architecture of human cognition? No. Jerry Fodor, perhaps the foremost critic of “massive modularity” admitted as much on the Amazon page selling his critical book on the subject: He concludes that although we have no grounds to suppose that most of the mind is modular, we have no idea how nonmodular cognition could work. Now, there is nothing in principle wrong with criticizing a hypothesis without suggesting an alternative, because sometimes we’ve just no good idea about how a phenomenon works. Nonetheless it is worth pointing out to contextualize the criticism, particularly those outside of mind sciences, that their position necessarily is or endorses “We have absolutely no idea how the mind could be wired, and insist that neither can anyone else. No hypotheses, no theories.” If you believe that something like plasticity is a competing hypothesis, please read Barrett & Kurzban.

The problem is that it works

The modularity model, whether or correct or not, has the advantage of generating empirically testable hypotheses. Combined with the evolutionary perspective, it makes predictions about the sorts of features a module must have which allows the testing of a suspected module to find out if it is or not. Brad Duchaine’s talk at HBES was a recounting of many studies along these lines testing or evaluating the facial recognition module hypothesis. The findings are all consistent with the hypothesis. John Tooby, Leda Cosmides and others have done similar work on the topic of adaptations (modules) for social exchange. With respect to specific types of modules, and therefore the basic plausibility of the model, the jury is in. The model has succeeded. The mind really does have functionally specific modules, even for so-called “higher” cognitive functions like social interactions. One might argue that a new jet design could never fly, but they ought to feel foolish doing so while cruising about at 30,000 feet. But that is essentially what the unsophisticated critics are doing.

Ever seen… life?

There’s a good reason that Fodor did not produce an alternative hypothesis: the very idea might not be coherent. Where there are biological functions, there is modularity. It is everywhere and at every scale of functionality in living things. Human limbs do not move via some homogeneous contractile sponge: they are composed of discrete parts which each have one or more functions: bones for structure, shape, and attachment of muscles; muscles contract, powering the motion; at least three other functionally distinct system work to maintain the former two parts- blood to bring fuel and remove waste, lymyphatic system to drain away wayward bits, and motor neurons to control the whole process remotely. All of these are functionally specific module systems (and they happen to be physically discrete as well).

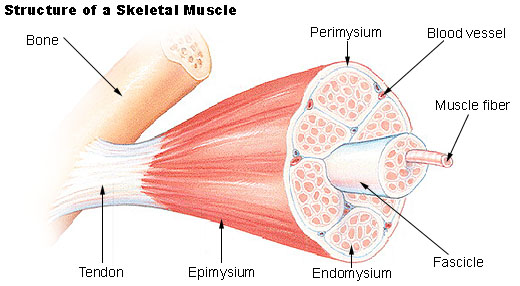

But wait, there’s more. Zoom in and you find that one tissue, like muscle, has its own function-specific needs and it thus has it’s own modular structure.

A muscle is not simply a bundle of long thin fibers, but a coordinated system with compartments and sheaths; specialized bits that attach to bone and help endure strain. You can zoom in further to individual fibers and see that they too have specialized parts, not some contractile soup.

Even gazing at the simplest life forms on Earth, prokaryotic bacteria, you can’t fail to notice that its biological functions are conducted by discrete little machines that we call organelles. It really seems to be modules all the way down, at least when it comes to adaptive biological functions. Is it really so strange to assume that the mind, an organ which clearly has evolved functions, has the properties of every bit of living matter we’ve ever seen?

Throughout history people have made many failed essentialist guesses about how invisible or incomprehensible biological systems worked. The bodily humors were magical essences and nothing more. Sperm cells were thought to contain homunculi, and thus simply be packets of preformed persons. Blood, long after the passing of the humors theory, was still considered an essence of a person or animal. Before the contents of cells could be seen clearly, but after cells themselves were rendered visible by microscopes, scientists like Thomas Huxley thought the basis of life was the “distribution of molecules” in the protoplasm. Some went so far as to try to produce synthetic protoplasm in the lab with the right mix of chemicals, not ever guessing the cells were made of tiny machines. So it may well be that the brain is the last stronghold of essentialist intuition. The last standing bodily humor theory perhaps: grey matter. Like the humors before it, working via some descriptive property like plasticity and certainly not through the intricate structuring of function-specific mechanisms as seen in all other living systems. I admit that there is some humor in it.

Further reading

Wikipedia

Clark Barrett and Robert Kurzban “Modularity in Cognition: Framing the Debate”

Jerry Fodor’s criticism of modularity in Steven Pinker’s How the Mind Works

Steven Pinker’s reply to Fodor