This writing is about why agnosticism is intellectually indefensible, and its mindspace competitor strong atheism is the most reasonable perspective. Frankly, there’s so much wrong with agnosticism I have to split into at least two posts. Unless you’re new to unbelief, you probably think you’ve heard every argument about agnosticism vs atheism (hereafter AvA): I promise in this part or part 2 you will read arguments or rationale that you’ve not seen articulated previously. This may be interesting for another reason: I am living dangerously by engaging in armchair philosophy on a network chock full of philosopher heavyweights who will be glad to swoop in and correct me. My hope is that they do so as necessary. I am not a professional, as they are, but these are topics I have been discussing and debating for about 20 years.

This writing is about why agnosticism is intellectually indefensible, and its mindspace competitor strong atheism is the most reasonable perspective. Frankly, there’s so much wrong with agnosticism I have to split into at least two posts. Unless you’re new to unbelief, you probably think you’ve heard every argument about agnosticism vs atheism (hereafter AvA): I promise in this part or part 2 you will read arguments or rationale that you’ve not seen articulated previously. This may be interesting for another reason: I am living dangerously by engaging in armchair philosophy on a network chock full of philosopher heavyweights who will be glad to swoop in and correct me. My hope is that they do so as necessary. I am not a professional, as they are, but these are topics I have been discussing and debating for about 20 years.

Caveats and definitions

This is not a primer on agnosticism. Please read a wiki if you are unacquainted. For the purposes of this writing, “agnostic” means someone who believes the god question cannot be answered, or else someone who has merely not been persuaded by evidence for or against the existence of god. “God” here means the god hypothesis, and refers to any transcendentally powerful creator being which people have sincerely believed in (no game-playing allowed). There may be other definitions of “god” or “God”, but they are not what I shall write about here.

I. The belief-knowledge false dichotomy

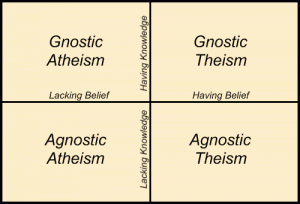

Agnostics often say that we can believe in a god (or disbelieve), but we can’t have knowledge there is or isn’t one. We shall set aside the obvious objection that if one existed, a God might pay us a visit and say hello, I am the creator! I think agnostics know that and discard it because it has never happened and is, prima facie, unlikely. So we have beliefs and knowledge. What do these words mean? In AvA discussions, belief is taken to be something we can’t prove or may not have evidence for; knowledge is a proposition which a rational observer is forced to accept by way of direct evidence or compelling argument. The agnostic tends to insist that knowledge and belief are categorically different. So different, they need to be put on different axes:

Except that they aren’t. Is there anything you would say that you know to be true, but do not believe to be? Why not? Aren’t knowledge and belief separate? The set of things we call knowledge is a subset of the things we call beliefs. What differentiates the two is merely the degree to which we should collectively be confident that it is correct. What we have is not two axes, but a single continuum of confidence. Often, individual ideas slide back and forth as our understanding advances.

The Higgs Boson was just a belief a year or ten ago, but today or very soon it will be knowledge. In 1900, the idea that the continents are fixed in their positions and do not move was knowledge, and supported as such by the world’s leading geologists. Today, the idea is a mere belief, an incorrect one. What establishes a proposition as knowledge? That is to say, justified and true? The short answer is, no one knows. There simply is no hard-and-fast way to tell. Science proceeds on the reliability of knowledge, the assumption what was true through the yesterdays will be true through the tomorrows, but the conclusion remains provisional, not decisive.

In science, we can make judgement calls based on standards of evidence, but plenty of propositions exist outside of what science can examine, such as one-of events. What if I witnessed the real killer of John F Kennedy but have no physical evidence? Would you really tell me that I “believe” it but do not “know” what I saw with my own eyes, merely because it can’t be proven in a laboratory? Alternately perhaps you would say I can know it but that you cannot. Fair enough, but isn’t it strange that there is absolutely no means, even in theory, to decide whether that proposition is knowledge or belief? Not if we understand the distinction is actually an arbitrary, if useful, one.

So it is, the two words are just ways of expressing how sure we are about the veracity of a proposition. The chart collapses, and the remaining axis is “confidence”. Qualms about why we should or should not be confident are accessory, the same as any two opposed positions.

II. Thomas Huxley: a deity late, an Allah short

The word “agnosticism” was coined by Thomas Huxley in 1869. This means that millennia of philosophical thought progressed without the need for a word for this position, including the entire Enlightenment period. Philosopher icons from Socrates to Spinoza, to Hume never uttered the word- not even the biggest contributors to the philosophy of theology and atheism. Don’t get me wrong, I am not saying people prior to 1869 did not fit the definition of “agnostic”- they surely did. But the big guys who tried to prove God by argument like Anselm and Descartes and big skeptical thinkers like Hume and Kant never once needed the term. The Greek word for atheist, conversely, is at least 2500 years old. This isn’t proof of much, but it is a rather curious fact.

Coming up in part 2: paradoxes, pretentiousness, and special pleading.