Charles Darwin called Embryology “The strongest class of facts” in support of his views, and made several observations to show that the theory of evolution explains a number of otherwise strange facts about animal development.

PBS hosts the fascinating interactive “Guess the Embryo” in which you can take a look at different vertebrate embryos and guess the species to which they belong. As you play the interactive, you’ll notice that the embryos look highly similar even though the adults are as different as night and day. Darwin noticed this, and thought that it could be best explained by common ancestry. He put forward two arguments to show that common ancestry predicted such similarities:

“As we have conclusive evidence that the breeds of the pigeon are descended from a single wild species, I compared the young within twelve hours after being hatched; I carefully measured the proportions (but will not here give the details) of the beak, width of mouth, length of nostril and of eyelid, size of feet and length of leg, in the wild parent-species, in pouters, fantails, runts, barbs, dragons, carriers, and tumblers. Now some of these birds, when mature, differ in so extraordinary a manner in the length and form of beak, and in other characters, that they would certainly have been ranked as distinct genera if found in a state of nature. But when the nestling birds of these several breeds were placed in a row, though most of them could just be distinguished, the proportional differences in the above specified points were incomparably less than in the full-grown birds.” (“Development and Embryology” ch.14, Origin of Species).

In the case of pigeons, Darwin had independently demonstrated that all of these strikingly different breeds were descended from a common ancestor. And among these birds, they looked almost exactly alike when they hatched, even though the adults were very different. So the lesson is that embryos and hatchlings of different breeds or species look almost identical.

Darwin’s second argument is a bit more theoretical; previously in the same chapter he notices that some features do not come about until late in development:

“It is notorious that breeders of cattle, horses, and various fancy animals, cannot positively tell, until some time after birth, what will be the merits or demerits of their young animals. We see this plainly in our own children; we cannot tell whether a child will be tall or short, or what its precise features will be.”

Breeders, as well as the process of natural selection, typically promote the increased reproduction of traits in a finished adult but not (necessarily) early development of a trait. As Darwin put it:

“It is of no importance to a very young animal, as long as it remains in its mother’s womb or in the egg, or as long as it is nourished and protected by its parent, whether most of its characters are acquired little earlier or later in life.”

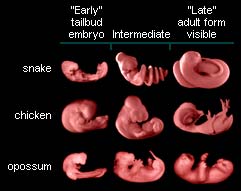

When plants and animals evolve, whether by natural or artificial selection, the new characteristics it evolves won’t all show up in early development, simply because there’s no reason for them too. Some of the new characteristics will show up late in development. And if some new characteristics show up late in development, that means that two species or breeds that share a common ancestor should look more similar in early development than late development. As demonstrated by “Guess the Embryo” as well as the following graph from UC Berkeley’s Explore Evolution, Darwin’s reasoning correctly predicts what we observe:

To be specific about the similarities, human embryos have an empty yolk sac (!) and a set of “arches” or “slits” around the neck that are identical in number and general appearance to the same structures that develop into the gills of fish! PZ Myers has written up a nice report of how these arches go on to develop into distinct organs in fish and humans; and the multiple lines of evidence showing an underlying similarity between them.

It’s such a shame that so many textbooks just present embryological similarity and say “this is evidence of common ancestry” without bothering to lay out the careful reasoning behind this beautiful argument. Now you know the best kept secret of theoretical embryology.

Two complications need to be added to this simple story.

First, the very earliest stages of zygote development are not always the same. Darwin himself had noted that their could be some evolved adaptations in that very earliest part of development, simply because the amount of egg yolk and other factors are different. If you look at development from “sperm hits egg” all the way to the hatched or birthed offspring, it’s really somewhere in the middle that we see the deep similarities between embryos. Some creationists have seized this as evidence against evolution, but it isn’t: remember, Darwin specified that only points in development that weren’t specifically fashioned by natural selection ought to be most similar, and that excludes the very early stages of development in many cases.

Second, there has been a new hypothesis put forward in modern times about the evolution of development. It’s the “developmental constraint hypothesis.” Jerry Coyne describes it like this:

“[D]evelopment is a very conservative process. Many structures that form later in development require biochemical “cues” from features that appear earlier. If, for example, you try to tinker with the circulatory system by remodeling it from the very onset of development, you might produce all sorts of adverse side effects in the formation of other structures, like bones, that musn’t be changed. To avoid these deleterious side effects, it’s usually easier to simply tack some less drastic changes onto [the] developmental plan.” (Why Evolution is True, p.78)

In other words, some parts of development are so important that evolution simply can’t change them (or can’t change them too much) and still produce a viable organism. That would explain why many things in development have stayed throughout evolution and are common to a wide range of species. Now this isn’t mutually exclusive with Darwin’s theory on the subject; Darwin’s hypothesis could explain some features of development while the constraint hypothesis may explain others. And that’s exactly what the most current research has found, see here.