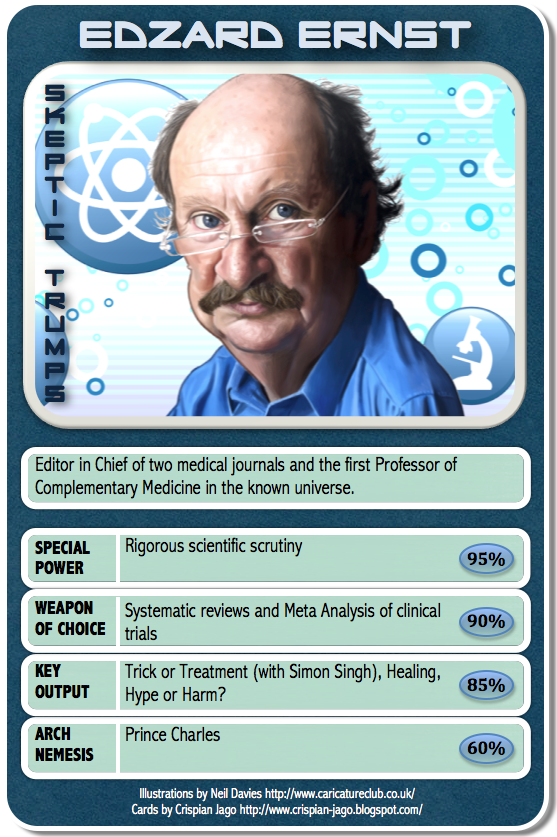

Edzard Ernst has one of the most impressive collections of letters behind his name that I’ve ever seen: MD, PhD, FMedSci, FSB, FRCP, FRCPEd. Originally from Germany, Ernst began his career as a physician there and, in addition to more standard medical training, also received training in a number of CAM modalities, including acupuncture, herbalism, homoeopathy, and spinal manipulation. He rose through the ranks to become Professor in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PMR) at the Hannover Medical School and Head of the PMR Department at the University of Vienna. At this point in his career, Professor Ernst took a decidedly different direction in life. He applied for and was hired as the first ever Laing Chair of Complementary Medicine at the University of Exeter (named for Sir Maurice Laing, who endowed the position) and so moved to the United Kingdom in 1993. He ascended to the position of Director of the Complementary Medicine Research Group in 2002. – Caleb Lack

Category Medicine

The activities of the dirtiest dozen aren’t unique. Ducktorism is widespread, often lucrative financially, and a menace to population health and society. Numerous promoters of woo, nostrums, and superstition violate consumer protection laws with impunity.

It would be wrong to describe the dirtiest dozen as representing the tip of the ducktorism iceberg only because icebergs are mostly hidden from view while ducktors operate in the open, largely unrecognized for what they are. Like Kevin Trudeau, many ducktors are bestselling authors and television celebrities with huge fanbases.

Most people have a hard time with these types of conditional probability problems even though the only math ability required to solve them is simple arithmetic. The challenge is to recognize how to arrange the arithmetic and have the patience to do so without getting mixed up. If you don’t trust me about the answers to the screening problem and you’re curious enough to see how I got them, here’s a step-by-step approach to arranging the arithmetic followed by a discussion of the practical implications for anyone thinking about getting screened for any disease.

A growing number of health care facilities require that all of their employees get the influenza vaccine every year in order to help prevent their patients from getting the flu. It’s a well known fact that handwashing is the single most effective way to prevent the spread of infections; however, vaccinations work even better in preventing the spread of influenza. Voluntary vaccination isn’t enough, however, to achieve herd immunity within the hospital community. For our employees, refusing the vaccine without a preapproved religious or medical exemption is grounds for dismissal.

On my to-do list today is grading the final exam in my “Introduction to Epidemiology” class. About a quarter of the exam addresses issues in screening for latent (subclinical) disease. In his 1986 book, Medical Care Can Be Dangerous to Your Health: A Guide to the Risks and Benefits, Eugene D. Robin provided this apt description of what screening programs do: Make patients out of normal human beings.

Sometimes journalists focus their efforts on distinguishing fact from fiction: they carry out well-planned, well-executed, objective investigations that yield illuminating findings about important issues. But when it comes to building and keeping an audience, telling an appealing story is often more important than proceeding properly with skeptical, truth-seeking investigation. The late Don Hewitt, creator and, for more than 35 years, executive producer of the extraordinarily successful CBS Television newsmagazine program “60 Minutes,” frequently suggested that the priority for journalists is summed up by four words: tell me a story.

Who here has trouble losing weight? Why I could not lose the weight baffled me. Well, it’s actually more complex than I thought. First, a lack of self-control is usually the knee-jerk assumption as to why you gain weight. This is based on the belief that weight loss is a simple matter of thermodynamics: one takes in more calories than one “burns”. That is true – but only to a point. I take a combination of psychiatric medications; the resulting weight gain is what the scientific literature calls “antipsychotic induced weight gain” (AIWG) (Lett et al., 2012, P. 242). Knowing mine is AIWG is frustrating: It is why my 900 calorie diet and exercise regimen do not work.

“What medications do you take?”

“What?” She appeared to be sleeping. I guess it took her a moment to realize she was in her hospital bed. I was waiting for her eyes to open. I don’t usually talk to the hospitalized patients directly, but in this case, I had to make an exception.

“I take lisinopril and metformin. Who are you?”

“I’m your pharmacist. I’m dosing the blood thinner your doctor prescribed for you… to help make sure you don’t get a stroke? Your lab work came back all wacky and I’m just trying to figure out why. Do you happen to be taking any dietary supplements?”

“Turmeric” she said. “It helps with my arthritis.”