This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the undergraduate and graduate students in my Science vs. Pseudoscience course. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Pseudoscience.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular pseudoscience topic, as well as run a booth on-campus to help reach people physically about the topic.

______________________________________________

The Bigger Deception by Tina Friar

Magic’s just science that we don’t understand yet. – Arthur C. Clarke

Perception deception is a sort of visual perception paradox in which we are absolutely certain we know what it is that we are seeing until it is shown to us (in no uncertain terms) that our interpretation of what we have just witnessed is completely wrong. One of the better known examples of this is the “impossible box” which was designed and built by Jerry Andrus. In this illusion, it seems that Andrus is inside a pen, but when looked at again more closely after he “magically” walks through the front of the pen, it becomes clear that something strange is afoot. While some call this magic, there is a much more logical explanation.

The human mind is constantly taking in and interpreting visual data, and sometimes our minds simply just get perspective wrong. There are many other fascinating illusions that prove that our minds are very good at playing some pretty good tricks on us. Some people insist that there must be something magical or even mystical about things that we do not understand. Noted psychologist Jim Alcock states that

Our brains are also capable of generating wonderful and fantastic perceptual experiences for which we are rarely prepared. Out-of-body experiences (OBEs), hallucinations, near-death experiences (NDEs), peak experiences….

When we are not prepared for these types of experiences, we at the very least shrug these things off as tricks or magic, and at the worst assign these occurrences far more meaning than they actually have. Why are many people inclined to believe that some extraordinary meaning exists for the things we cannot immediately understand or explain?

While illusions and other sorts of seemingly external experiences seem magical to some, they are actually things that occur within our minds, and are often relatively easy to explain. Most illusions are merely a matter of perspective and perception, or more accurately skewed perspective and misperception. Many people have no idea how the mind actually perceives objects and have never been educated on how perspective actually works. Without this knowledge, it is easier to buy into the notion that something magical or mystical is occurring when this is far from the case.

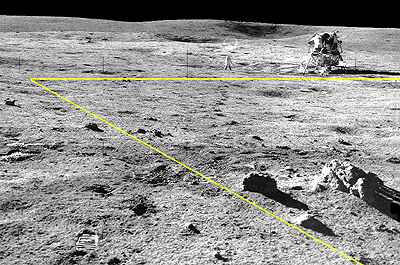

Explaining how perspective works goes a long way toward explaining many illusions and visual deceptions. According to one definition, “perspective, in context of vision and visual perception, is the way in which objects appear to the eye based on their spatial attributes; or their dimensions and the position of the eye relative to the objects”. The keys in this definition logically may be “spatial attributes” and “position of the eye relative to the objects”. Common sense should dictate that both the way the object one is viewing is positioned and how the viewer themselves are positioned in relation to said object will affect how the viewer’s mind arranges and makes sense of the visual input. We are not really taught about how this process works. A fine example of our lack of understanding of perspective is the long running conspiracy theory stating that the Apollo moon landing was a hoax. The picture below (from the Skeptic’s Dictionary website) demonstrates one of the common arguments those deniers use: that because there are multiple shadows going in different directions, this must mean that artificial light was used in the scene in the photograph. This page on the Skeptic’s Dictionary site explains in greater detail how this is not necessarily the case. Shadows cast different angles depending upon where the observer is standing in relation to both the objects they are viewing and the light source which creates them. In other words, where both the viewer is and where the object being observed is spatially affects the viewer’s perception of said object.

The inner workings of perception also lend some clarity as to why our eyes often deceive us and our brains follow suit. While there are no absolute answers as to how exactly the brain perceives visual stimuli, the it is accurate to say that

Visual perception is one of the senses, consisting of the ability to detect light and interpret (see) it as the perception known as sight or naked eye vision…..The major problem in visual perception is that what people see is not simply a translation of retinal stimuli (i.e., the image on the retina).

Because visual perception is not merely a simple interpretation of what our eyes take in and send to our visual cortex, we can be tricked into seeing things that are not actually there or misunderstanding the things that we do see.

There are a number of possible reasons why people might take the “easy route” and assume that things which are not easily explained are merely trickery or mystical or even some form of true magic. One explanation that may give us some insight into this behavior is simply that critical thinking is not a skill which comes naturally to us. These skills take practice and work to develop. It is much easier to blindly accept something as fact than to take the time and make the effort to critically examine the facts or to even seek out those facts in the first place. In his article The Belief Engine, Jim Alcock says it well when he says “The true critical thinker accepts what few people ever accept — that one cannot routinely trust perceptions and memories.”

There is no shortage of ways in which our minds can play tricks on us. However, the bigger deception may very well be the more serious trickery which we commit toward ourselves. By blindly believing or fabricating reasons for the phenomena we do not understand in our world instead of taking the time to learn about how our minds actually work, we not only do a disservice to ourselves and our fellow man, but we commit one of the biggest deceptions of all.