This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the graduate students in my Psychopathology course. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Mental Health.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular class of mental disorders.

______________________________________________

A Brief History of Conversion Disorder by Sarai Peguero

Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders is a class of disorders in the DSM-5 primarily classified by somatic symptoms. By “somatic symptoms,” we mean physical symptoms that appear to be caused by mental distress. One of the disorders in this class is Conversion Disorder (also known as Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder). This disorder is described by an alteration or a loss of physical functioning without any identitifiable neurological or medical cause. These alterations of physical functioning are usually a result of underlying stress in the individual’s life. Very rarely are these symptoms caused by a medical issue that was missed. These symptoms can manifest as temporary paralysis or blindness, psychogenic seizures, or muscle spasms, to name just a few potential symptoms.

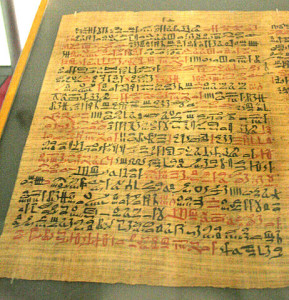

The first documented cases of what we know call conversion disorder date back to ancient Egypt and around 1900 BC in the Eber Papyrus, the oldest medical document discovered. The Eber Papyrus describes symptoms of seizures and a sense of suffocation. This sense of suffocation is known as globus istericus, or more commonly “lump in the throat.” The Egyptians believed that these symptoms, which were primarily seen in women, were caused by the position of the woman’s uterus, also called the “wandering uterus.” This was treated by placing pleasant spices and aromas near her mouth if the uterus was thought to have moved downward, and vice versa if the uterus was thought to have moved upward.

The first documented cases of what we know call conversion disorder date back to ancient Egypt and around 1900 BC in the Eber Papyrus, the oldest medical document discovered. The Eber Papyrus describes symptoms of seizures and a sense of suffocation. This sense of suffocation is known as globus istericus, or more commonly “lump in the throat.” The Egyptians believed that these symptoms, which were primarily seen in women, were caused by the position of the woman’s uterus, also called the “wandering uterus.” This was treated by placing pleasant spices and aromas near her mouth if the uterus was thought to have moved downward, and vice versa if the uterus was thought to have moved upward.

Hippocrates was the first to coin the term “hysteria” for these symptoms in late 5th century BC. The word hysteria comes from the Greek word for uterus, hysterika. Hippocrates thought the uterus wandered due to a lack of a normal sexual life. Both Plato and Aristotle shared Hippocrates’ beliefs. Hippocrates explained that these abnormal uterine movements caused various kinds of symptoms like anxiety, a sense of suffocation, tremors, paralysis, and convulsions. He also differentiated between hysteria and epileptic convulsions. He describes epilepsy as compulsive movements caused by the brain, while hysteria consisted of abnormal movements caused by the wandering uterus. The treatment of hysteria at this time in history was much like the ancient Egyptians. Women were to cure themselves by placing pleasant aromas and spices in the opposite direction the uterus moved in in order to return it to its natural position inside the body. Common aromas used were mint, belladonna extract, hellebore, and valerian.

Four centuries later, in 1st century AD, Aulus Celsus clinically described hysteria and its symptoms in De re medica. He wrote that

In females, a violent disease also arises in the womb; and next to the stomach, this part is most sympathetically affected or most sympathetically affects the rest of the system. Sometimes also, it so completely destroys the senses that on occasions the patient falls, as if in epilepsy. This case, however, differs in that the eyes are not turned, nor does froth issue forth, nor are there any convulsions: there is only a deep sleep.

Celsus is accurate in his definition by explaining that these symptoms are in fact occurring, but are different and not brought about by their usual cause. Therefore, “there is only a deep sleep”. The treatment of hysteria in this time was reformed by Soranus, the founder of scientific obstetrics and gynecology. He wrote a treatise on women’s diseases where he says that pleasant aromas are ineffective at treating the hysterical woman. Soranus states that massages, exercise, and hot baths are the best treatment and prevention methods for women’s diseases, including hysteria.

Celsus is accurate in his definition by explaining that these symptoms are in fact occurring, but are different and not brought about by their usual cause. Therefore, “there is only a deep sleep”. The treatment of hysteria in this time was reformed by Soranus, the founder of scientific obstetrics and gynecology. He wrote a treatise on women’s diseases where he says that pleasant aromas are ineffective at treating the hysterical woman. Soranus states that massages, exercise, and hot baths are the best treatment and prevention methods for women’s diseases, including hysteria.

Another gynecologist and an advocate for women’s health in the middle ages was Trota of Salerno. Trota was one of the authors who wrote the Trotula, a collection of three texts on women’s medicine around the 12th century in which hysteria is looked at. Trota sought to understand women’s diseases without being influenced by the prejudices of the time. She acknowledged women were more vulnerable than men regarding their gynecological diseases, and she understood that out of shame women typically do not reveal their distresses to their male doctors. Much like Hippocrates, Trota believed hysteria was caused by abstaining from sex and sexual activity, and she gave advice to her patients on how to appease sexual desire.

The treatment of hysteria remained the same in the beginning of the 13th century. The view on women was also unchanged. Many treatises, such as The Canon of Medicine of Avicenna, written at this time described women as the cause of the disease, rather than as a patient in need of treatment. St. Thomas Aquinas frequently discloses his dislike for women in his work Summa Theologica. He expresses how women should have not been created in the first place, how women are failed men, and how they are the result of sin. Aquinas also alludes to how old women are evil, look at children in a toxic way, and are witches who cooperate with demons. From this moment on, mental illnesses were seen as a connection between women and the devil. As a result, the treatment for hysteria went from spices and pleasant aromas to exorcism. Exorcism at this time was seen as a cure, and not a punishment. Hysteria was often confused as witchcraft in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. This was due to physicians not being able to identify the cause of the disease, and therefore attributed it to the devil. At this point, exorcism was a punishment and no longer a cure. To properly be able to identify and prosecute these “witches,” Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger wrote the Malleus Maleficarum, or Hammer of the Witches. Thousands of innocent women were killed as a result of this book.

It wasn’t until the late 1600s that hysteria was revolutionized. Thomas Willis was the first to no longer attribute hysteria to the wandering uterus, but instead relate it to the nervous system and brain. Around the same time, Thomas Sydenham published an epistolary dissertation on hysteria. Here he recognizes that the symptoms of hysteria can be simulated across all areas of organic diseases. Sydenham also believes the uterus is not the cause of hysteria, as Willis stated beforehand, and also relates hysteria to hypochondriasis. In his dissertation, Sydenham sways between hysteria being explained psychologically or somatically. We are still not certain of this today as the ICD-10 categorizes conversion disorder as a dissociative disorder, while the DSM-5 categorizes it as a somatic symptom disorder.

Hysteria was no longer thought to be a relationship with Satan after the Enlightenment in the 18th century; mental illnesses began to be regarded in a scientific light. It is now that hysteria is progressively associated with the brain rather than the uterus. In the early 1900s, Pierre Janet conducted studies on patients with hysteria and determined that hysteria is the patient’s idea of pathology that is then converted into a physical disability. Several year later, Sigmund Freud and Joseph Breuer also conducted studies on several patients with hysteria. It was Freud who then coined the term “conversion disorder”, but it was not officially renamed from hysterical neurosis in the DSM-II until the DSM-III in 1980. He believed these symptoms were a result of underlying distress, and the brain subconsciously converted this stress into a physical impairment in order to relieve the patient’s anxiety.

Hysteria was no longer thought to be a relationship with Satan after the Enlightenment in the 18th century; mental illnesses began to be regarded in a scientific light. It is now that hysteria is progressively associated with the brain rather than the uterus. In the early 1900s, Pierre Janet conducted studies on patients with hysteria and determined that hysteria is the patient’s idea of pathology that is then converted into a physical disability. Several year later, Sigmund Freud and Joseph Breuer also conducted studies on several patients with hysteria. It was Freud who then coined the term “conversion disorder”, but it was not officially renamed from hysterical neurosis in the DSM-II until the DSM-III in 1980. He believed these symptoms were a result of underlying distress, and the brain subconsciously converted this stress into a physical impairment in order to relieve the patient’s anxiety.

During the late 19th and 20th centuries, cases of conversion disorder dropped by almost two–thirds and then continued to decline. What might cause this dramatic decline in a once very prevalent condition? It has been suggested that syphilis mimics the same symptoms and effects as conversion disorder if gone untreated, and being able to differentiate between the two dropped cases of conversion disorder. Another suggestion is that the social circumstances for women that produced conversion disorder in the first place are no longer in effect. Women have essentially been emancipated. Both of these theories are plausible when we take into account that conversion disorder typically occurs in populations with low socio-economic status, less educated individuals, and in strict social systems that prevent the individual from directly expressing their thoughts and feelings.

The history of conversion disorder is interesting and extensive. From wandering uteruses to demons to underlying stress, several names changes, and dissociation or somatization, conversion disorder has seen it all. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the symptoms these individuals are experiencing are very real, and are not feigned in any way. These individuals must be taken seriously so they can receive effective treatment and get back to living their lives.