This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the graduate students in my Psychopathology course. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Mental Health.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular class of mental disorders.

______________________________________________

A Brief History of PTSD by J. Kyle Haws

Human beings evolved to live together in groups looking for food, hunting and gathering. But early human ancestors lived in a daunting and relentless world in which they often experienced life-threatening stressors. Today, traumatic events can often lead to the development of what is called posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD is considered a recent psychological diagnostic phenomenon making its debut in the DSM-III. Although the diagnosis is relatively new, the disorder itself is considerably older. While we have no way of knowing if our early human ancestors developed PTSD, we do have evidence that these symptoms have been with us for quite some time.

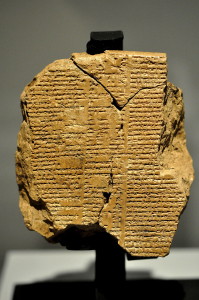

The earliest evidence of PTSD is found in mankind’s oldest literature. For example, PTSD symptoms are found in Epic of Gilgamesh. PTSD symptoms have also been found in the Iliad and in the Odyssey. The Bible has several examples of PTSD symptomology, specifically in Psalm 137. Several poets and novelists have recorded the impact severe traumatic stress can have on feelings, behavior, and cognition.

The earliest evidence of PTSD is found in mankind’s oldest literature. For example, PTSD symptoms are found in Epic of Gilgamesh. PTSD symptoms have also been found in the Iliad and in the Odyssey. The Bible has several examples of PTSD symptomology, specifically in Psalm 137. Several poets and novelists have recorded the impact severe traumatic stress can have on feelings, behavior, and cognition.

In Henry IV, written by Shakespeare, there is an account about Hotspur and his odd behavior, which was the product of multiple combats. His behavior meets the criteria for diagnosis of PTSD. Hotspur’s life is filled with significant traumatic events. Hotspur frequently re-experiences the trauma. He exhibits diminished interest in sex and isolates himself. He has difficulty sleeping and is easily agitated and irritable. His symptoms have been apparent for large duration of his life. With all this evidence it is easy to conclude that Shakespeare has provided one of the earliest descriptions of the disorder.

While PTSD made its psychiatric and medical debut at the end of the Vietnam War, there is an abundance of historical accounts demonstrating the ubiquity of PTSD during the American Civil War. Historians and clinicians have started to examine historical accounts of PTSD and its possible links to suicide in the 1860s. During the Civil War over a million Americans were killed. This number alone fails to represent the psychological scars that were inflicted during this time of war and death. Medicine did not understand how war and traumatic experiences could distress the mind. The Civil War occurred in an epoch when modern scientific understanding and concern for mental wellbeing did not exist. Any mental disorder was a mark of shame, especially for soldiers cultivated in the culture of chivalry and courage. Wounded soldiers who managed to survive battle were subject to the archaic medicinal practices, which included barbaric methods such as amputations with unsterilized bone saws.

During the bloodiest day of combat in U.S. history almost all of the 16th Connecticut regiment were captured in Antietam. The 16th regiment was sent to a Confederate prison where a third of the prisoners died from starvation and disease. At the end of the war and upon returning home, many of the survivors became emotionally numb and abusive. Many of the survivors lived a few independent years before either committing suicide or being committed to an asylum. William Hancock, a survivor of the Confederate prison, had gone to war “a strong young man and returned broken in body and mind.” At the end of the war, returning soldiers were afflicted with physical wounds, malaria, chronic diarrhea, and psychologically destroyed. Wallace Woodford dreamt that he was still searching for food at the prison. He died at the age of 22 and his headstone reads: ”8 months a sufferer in Rebel prison; He came home to die.” John Hildt, a 25-year-old corporal, lost a limb because of combat and was transferred to a hospital for the insane because of “acute mania.” Hildt had no previous history of psychopathology. Hildt spent many years in the hospital but his condition never approved. Hildt died in the hospital in 1911 as another casualty of war 50 years later.

During the bloodiest day of combat in U.S. history almost all of the 16th Connecticut regiment were captured in Antietam. The 16th regiment was sent to a Confederate prison where a third of the prisoners died from starvation and disease. At the end of the war and upon returning home, many of the survivors became emotionally numb and abusive. Many of the survivors lived a few independent years before either committing suicide or being committed to an asylum. William Hancock, a survivor of the Confederate prison, had gone to war “a strong young man and returned broken in body and mind.” At the end of the war, returning soldiers were afflicted with physical wounds, malaria, chronic diarrhea, and psychologically destroyed. Wallace Woodford dreamt that he was still searching for food at the prison. He died at the age of 22 and his headstone reads: ”8 months a sufferer in Rebel prison; He came home to die.” John Hildt, a 25-year-old corporal, lost a limb because of combat and was transferred to a hospital for the insane because of “acute mania.” Hildt had no previous history of psychopathology. Hildt spent many years in the hospital but his condition never approved. Hildt died in the hospital in 1911 as another casualty of war 50 years later.

The circumstances of each war can affect the psyche of soldiers in different ways. World War I was fought in the trenches and was marked with artillery bombardments, which gave rise to “shell shock” and “gas hysteria,” a fear of a poisonous gas attack. Later it was recognized that all soldiers had a breaking point, known as “combat fatigue” and “old sergeant’s syndrome.”

In 1952, the APA published the First Edition of the DSM, which included a category called “Gross stress reaction.” This was an ill-defined diagnosis for classifying individuals who had been psychologically affected by exposure to stress. The major problem with gross stress reaction was that it was considered a temporary diagnosis, which would later become a neurotic reaction if the symptoms persevered.

DSM-II abolished gross stress reaction, leaving clinicians without options for diagnosing individuals who had catastrophic experiences. In the 1970s, many clinicians recognized the need for a new diagnosis for patients suffering from severe and chronic symptoms preceded by exposure to traumatic events. A number of syndromes had been described in the literature and influenced the formulation of DSM-III and subsequent editions. But the impetus of thinking about psychological damage caused by trauma begins not with a war but with a flood.

On February 26, 1972, the dam on Buffalo creek in West Virginia collapsed, and within a few seconds 132 million gallons of water roared down upon the residents of the Appalachian mountain hollows. Kai Erickson, the son of Erik Erikson, wrote a book about this disaster and provided detailed criteria for diagnosing PTSD using the survivors as case studies.

Two years later, Wilbur and his wife described their experiences after that horrendous and destructive day.

What I went through on Buffalo Creek is the cause of my problem. The whole thing happens over to me even in my dreams, when I retire for the night. In my dreams, I run from water all the time, all the time. The whole thing just happens over and over again in my dreams…

They had become emotionally anesthetized to the joys and sorrows of the world.

I didn’t even go to the cemetery when my father died (about a year after the flood). It didn’t dawn on me that he was gone forever. And those people that dies around me now, it don’t bother me like it did before the disaster. It just didn’t bother me that my dad was dead and never would be back. I don’t have the feeling I used to have about something like death. It just don’t affect me like it used to.

Wilbur experiences anxiety, including hyper-alertness and phobic to events that remind him of the flood.

I listen to the news, and if there is a storm warning out, why, I don’t go to bed that night. I sit up. I tell my wife, “Don’t undress our little girls; just let them lay down like they are and go to bed and go to sleep and then if I see anything going to happen, I’ll wake you up in plenty of time to get you out of the house.” I don’t go to bed. I stay up.

My nerves is a problem. Every time it rains, every time it storms, I just can’t take it. I walk the floor. I get so nervous I break out in a rash. I am taking shots for it now.

Wilbur also suffers from survival guilt:

At that time, why, I heard somebody holler at me, and I looked around and saw Mrs. Constable… She had a little baby in her arms, and she was hollering, “Hey, Wilbur, come and help me; if you can’t help me, come get my baby” .. But I didn’t give it a thought to go back and help her. I blame myself a whole lot for that yet. She had her baby in her arms and looked as though she were going to throw it to me. Well, I never thought to go help that lady. I was thinking about my own family. They all six got drowned in that house. She was standing in water up to her waist, and they all got drowned.

Sadly, Wilbur’s tale of distressing survival is not an aberration but a ubiquitous phenomenon that has occurred frequently through out history. Wilbur’s horrific experience and those of others paved the way for the inclusion of PTSD in DSM-III. Allowing practitioners and researchers to understand the disorder and discover treatments to alleviate the symptoms. Even though Wilbur’s experience caused him suffering and grief it provided additional knowledge for professionals to understand this phenomenon and provide healing for those similarly afflicted. Evidence of PTSD can be found where ever catastrophic experiences have occurred. The human species has evolved through millennia of trauma and the usual response to high adversity is resilience and growth. Unfortunately, not everyone that experiences catastrophic events develops resiliency and growth. Most individuals who developed PTSD never acquired the necessary support and treatment to alleviate their suffering. Hopefully through increased awareness and advancements in science less people will have to live through the same agony as our predecessors.