This post is part of a series of guest posts on GPS by the graduate students in my Psychopathology course. As part of their work for the course, each student had to demonstrate mastery of the skill of “Educating the Public about Mental Health.” To that end, each student has to prepare two 1,000ish word posts on a particular class of mental disorders.

______________________________________________

The Often Ignored Cognitive Consequences of HIV/AIDS by Lee Bailey

I would like to think that we have come a long way in regards to our knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS. Historically speaking, it wasn’t that long ago that symptoms of AIDS were first clinically observed in the United States. The year was 1981 and there were growing reports of patients (mostly injection drug users and gay men) who were exhibiting signs of impaired immunity without any apparent cause. The CDC and early researchers, via the media, coined the acronym GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) and the phrase “the 4H disease” because the disease seemed to be infecting mostly homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians. Thankfully, by the end of 1982, those terms were abandoned and the CDC started using the term AIDS (Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). By 1984, two independent research teams had isolated the retrovirus that would be found to be the cause of AIDS, and in 1986 the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses officially named it HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus). Over the last 30 years, we have learned a great deal about HIV/AIDS including its symptoms, how it spreads, how to prevent transmission, and how to manage HIV to prevent it from progressing into AIDS. Most of us have had a fair dose of HIV/AIDS awareness throughout our lives, but there is one facet of the disease that has slipped through the cracks. We know to practice safe sex, to get tested regularly, and how the HIV virus compromises our immune system to the point where the common illnesses can kill us. What is not talked about enough is the effect that HIV has on the brain and the cognitive impairments it can cause if not managed successfully.

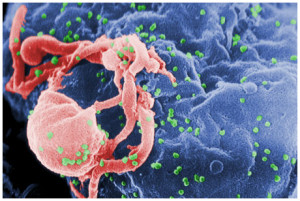

HIV does more than just wreak havoc on our immune system. It is also diabolical in its ability to infiltrate the brain and disable some of our most important cognitive functions. Usually, our brain is protected by the blood brain barrier (BBB), but HIV is able to sneak in via infected microglia. These are the cells in the brain and spinal cord that serve as the first line of active immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS). Once activated by HIV, the microglia secrete neurotoxins and convince other cells to do the same. Research has shown this process to play a vital role in the pathogenesis (development) of HIV, and a positive correlation is seen between the levels of those neurotoxins and severity of neurocognitive disease. Following CNS infiltration, neuronal destruction ensues with gliosis, compromised dendritic processes, and weakened myelin sheaths. This ultimately results in cognitive impairment and a diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND).

HIV does more than just wreak havoc on our immune system. It is also diabolical in its ability to infiltrate the brain and disable some of our most important cognitive functions. Usually, our brain is protected by the blood brain barrier (BBB), but HIV is able to sneak in via infected microglia. These are the cells in the brain and spinal cord that serve as the first line of active immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS). Once activated by HIV, the microglia secrete neurotoxins and convince other cells to do the same. Research has shown this process to play a vital role in the pathogenesis (development) of HIV, and a positive correlation is seen between the levels of those neurotoxins and severity of neurocognitive disease. Following CNS infiltration, neuronal destruction ensues with gliosis, compromised dendritic processes, and weakened myelin sheaths. This ultimately results in cognitive impairment and a diagnosis of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND).

HAND is diagnosed once cognitive impairment from HIV/AIDS meets criteria for mild/major neurocognitive disorder. There are three types of HAND: Asymptomatic Neurocognitive Impairment (ANI), Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (MND), and HIV-Associated Dementia (HAD). The lives of those living with MND and HAD are compromised in a variety of ways. Cognitive impairment can manifest as an overall slowing of mental processes including, but not limited to, impaired memory and concentration, and verbal fluency. Motor impairments can include tremors, poor balance, and the deterioration of fine motor control, which causes a loss of hand dexterity and clumsiness. Behavioral changes can manifest as well, and individuals are seen to be indifferent about life in general, with a lack of passion, interest, or concern about most things. Their emotions may seem suppressed as well because of their inability to show signs of excitement, or even contentment. These symptoms are often accompanied by extreme fatigue and/or daytime sleepiness. In addition to these impairments, psychological dysfunctions have also been observed. Those affected by HIV seem to be more likely to meet criteria for major depressive disorder and suffer from alexithymia.

Our biggest defense against the progression of HIV into AIDS and/or HAND is highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). HAART is actually a personalized combination of antiretroviral drugs that act on difference phases of the HIV life cycle in order to manage the disease and stifle its progression. Ideally, it helps prevent opportunistic infections from becoming deadly by helping to maintain the infected person’s immune system. It has also been proven to lower the levels of active virus within the host, sometimes to an undetectable level, which can also lower the likelihood of transmission. HAART has proven itself to be so effective at managing HIV/AIDS and HAND that the Department of Health and Human Services, as well as other organization worldwide, suggest it for all patients testing positive for HIV. The use of HAART has not only reduced new diagnoses of HIV per year by almost half, but also greatly lowered the prevalence of HAND, or major neurocognitive disorder. However, because HAART is enabling people to live longer with HIV, the prevalence of less severe forms of HAND, Neurocognitive Impairment (ANI) and Mild Neurocognitive Disorder (MND), are increasing every year. This can be seen as a good thing though since what was once considered a death sentence has been mostly reduced to a chronic illness that requires long-term pharmacological management. Unfortunately, the only way to eradicate HAND is through a cure for HIV.

Over the past few years, research has taken leaps and bounds towards a cure for AIDS. Whether it be the “Berlin patient” who was seemingly cured by undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat his leukemia, or the research team that essentially “deleted” the HIV virus from human DNA, each of these accomplishments takes us one step closer to finding a cure to one of the world’s most costly and deadly diseases. Over 40 million lives have been lost to AIDS and approximately 35 million are living with HIV/AIDS today. Sadly, only 19 million of them know their status and only 13 million of them are receiving antiretroviral therapy. Until a cure is found, HIV education, an increased screening initiative, and making HAART available to everyone affected are our best lines of defense.