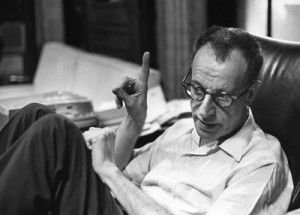

For those who may not have been paying attention, I’m a clinical psychologist. Specifically, I am a cognitive-behavioral therapist, meaning that I use evidence-based methods of changing what you do and how you think to change how you feel. I am also a professor who teaches graduate students and others how to do CBT, primarily for the treatment of anxiety and repetitive behavior disorders. One thing I like to help my students understand is how we arrived at where we are today, who the pioneers in our field were that helped get the ball rolling and turn “talk therapy” from a pseudoscientific enterprise to an evidence-based practice (EBP). Among famous figures like Aaron Beck, Albert Bandura, and Joseph Wolpe, Dr. Albert Ellis is often hailed as one of the most highly influential people on the move to EPB in psychology, and rightfully so. From the FFRF’s write-up of the man:

For those who may not have been paying attention, I’m a clinical psychologist. Specifically, I am a cognitive-behavioral therapist, meaning that I use evidence-based methods of changing what you do and how you think to change how you feel. I am also a professor who teaches graduate students and others how to do CBT, primarily for the treatment of anxiety and repetitive behavior disorders. One thing I like to help my students understand is how we arrived at where we are today, who the pioneers in our field were that helped get the ball rolling and turn “talk therapy” from a pseudoscientific enterprise to an evidence-based practice (EBP). Among famous figures like Aaron Beck, Albert Bandura, and Joseph Wolpe, Dr. Albert Ellis is often hailed as one of the most highly influential people on the move to EPB in psychology, and rightfully so. From the FFRF’s write-up of the man:

Ellis initially practiced psychoanalysis, but in 1953 he declared it unscientific and became what he called a “rational therapist.” In 1955, he invented Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), a type of short-term Cognitive Behavioral Therapy which counsels patients to take action to improve their lives in the present, rather than focusing on past experiences. He founded the non-profit Albert Ellis Institute in 1964, which worked to promote REBT and make it accessible. REBT is still practiced today and was considered a revolutionary change in psychotherapy. In fact, a 1982 study found that Albert Ellis was considered more influential than such famous psychologists as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung.

And from the institute that bears his name:

He published his first book on REBT, How to Live with a Neurotic, in 1957. Two years later he organized the Institute for Rational Living, where he held workshops to teach his principles to other therapists. The Art and Science of Love, his first really successful book, appeared in 1960, and he has now published 54 books and over 600 articles on REBT, sex and marriage. Until his death on July 24, 2007, Dr. Ellis served as President Emeritus of the Albert Ellis Institute in New York, which provides professional training programs and psychotherapy to individuals, families and groups.

The man left an enormous legacy behind him, and the work he did has had a tremendous positive impact on innumerable lives.

But, a side of him that is rarely mentioned (at least in psychological circles) is his religious beliefs, or lack thereof. From early in his career, Ellis pushed back against religious beliefs as being a good thing, although his views apparently softened a bit as he aged. While he continued to describe himself as an atheist and touted that as the most mentally healthy view toward religion, he stopped denouncing all of religious as potentially bad for one’s mental well-being.

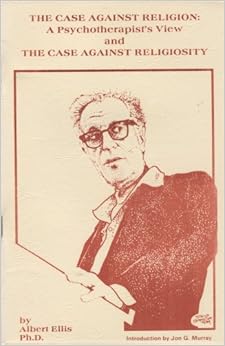

Still, his 1980 pamphlet The Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity is quite an interesting (and quick!) read. Some excerpts of particular interest:

Still, his 1980 pamphlet The Case Against Religion: A Psychotherapist’s View and the Case Against Religiosity is quite an interesting (and quick!) read. Some excerpts of particular interest:

If religion is defined as man’s dependence of a power above and beyond the human, as a psychotherapist I find it to be exceptionally pernicious. For the psychotherapist is normally dedicated to helping human beings in general, and his patients in particular, to achieve certain goals of mental health, and virtually all these goals are antithetical to a truly religious viewpoint.

In a sense, the religious person must have no real views of his own; and it is presumptuous of him, in fact, to have any. In regard to sex-love affairs, to marriage and family relations, to business, to politics, and to virtually everything else that is important in his life, he must try to discover what his god and his clergy would like him to do; and he must primarily do their bidding.

Democracy, permissiveness, and the acceptance of human fallibility are quite alien to the real religionist—since he can only believe that the creeds and commands of his particular deity should, ought, and must be obeyed, and that anyone who disobeys the is patently a knave.

Religion, then, by setting up absolute, god-given standards, must make you self-deprecating and dehumanized when you err; and must lead you to despise and dehumanize others when they act badly. This kind of absolutistic, perfectionistic thinking is the prime creator of the two most corroding of human emotions: anxiety and hostility.

In the final analysis, then, religion is neurosis. This is why I remarked, at a symposium on sin and psychotherapy held by the American Psychological Association a few years ago, that from a mental health standpoint Voltaire’s famous dictum should be reversed: for if there were a god, it would be necessary to uninvent him.

I’d really recommend going and give the whole thing a read, really thought-provoking stuff.