As mentioned in my previous posts, this is the fifth post in a seven part series examining science and pseudoscience in the field of personality and psychopathology assessment. My goal for the prior three posts and this one is to expose the less than stellar underbelly of some of the most commonly-used and well known measures, particularly those that fall under the grouping of “projective” assessments. The fourth measure I will turn a careful and critical eye to are sentence completion tasks.

——————————————————

The single most frequently used projective method by school psychologists, employed by approximately 60% in the most recent survey (Hojnoski et al., 2006), sentence completion tests (SCTs) are also commonly used by clinical psychologists for both adult and child evaluations (Archer & Newsom, 2000; Camara, Nathan, & Puente, 2000; Hogan, 2005). Compared to the other methods reviewed in this series, SCTs actually have the longest history of usage and, much like the Rorschach, began life in the realm of experimental psychology. The earliest SCT appears to have been constructed by Herman Ebbinghaus (1897), who used them to examine reasoning and intelligence in adolescents. Their first usage to examine personality and psychopathology began with Carl Jung’s theories concerning free word association, which developed into formalized procedures involving only a one word stimulus and response (for examples see Kent & Rosanoff, 1910; Rapaport, Gill, & Schafer, 1946). This evolved into short phrases, and finally sentences and measures quite similar to those used today by the 1930s (Weiner & Greene, 2008). A common thread among the early clinical users of SCTs was that the responses they generated were not simply self?report, but were instead providing a view into inner, conflicts, desires, and wishes (Holsopple & Miale, 1954; Rohde, 1946).

The single most frequently used projective method by school psychologists, employed by approximately 60% in the most recent survey (Hojnoski et al., 2006), sentence completion tests (SCTs) are also commonly used by clinical psychologists for both adult and child evaluations (Archer & Newsom, 2000; Camara, Nathan, & Puente, 2000; Hogan, 2005). Compared to the other methods reviewed in this series, SCTs actually have the longest history of usage and, much like the Rorschach, began life in the realm of experimental psychology. The earliest SCT appears to have been constructed by Herman Ebbinghaus (1897), who used them to examine reasoning and intelligence in adolescents. Their first usage to examine personality and psychopathology began with Carl Jung’s theories concerning free word association, which developed into formalized procedures involving only a one word stimulus and response (for examples see Kent & Rosanoff, 1910; Rapaport, Gill, & Schafer, 1946). This evolved into short phrases, and finally sentences and measures quite similar to those used today by the 1930s (Weiner & Greene, 2008). A common thread among the early clinical users of SCTs was that the responses they generated were not simply self?report, but were instead providing a view into inner, conflicts, desires, and wishes (Holsopple & Miale, 1954; Rohde, 1946).

Given that there are well over 40 published SC measures (Sherry, Dahlen, & Holaday, 2004), I will focus on only two: the most widely used measure, the Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank (RISB), and the most heavily researched measure, the Washington University Sentence Completion Test (WUSCT). It should be cautioned, however, that it is unlikely that the below information can generalize to other SCTs.

The RISB (Rotter & Rafferty, 1950; Rotter, Lah, & Rafferty, 1992) is the most used SCT according to surveys of clinical psychologists (Holaday et al., 2000). Originally developed for assessing combat veterans returned from World War II, it was later adapted to be used with high school students, college students, and adults. The manual for the RISB described it as a screening measure for overall adjustment, not intended for comprehensive personality assessment or diagnostic usage. In sharp contrast the RISB, the WUSCT (Hy & Loevinger, 1996) was developed as a research, not clinical, measure. Constructed to measure Loevinger’s (1976) theory of ego formation, it has been found to be only rarely used clinically (Holaday et al., 2000), but does have a larger body of research on it than any other SCT (Westenberg, Hauser, et al., 2004). Both measures have objective scoring procedures for each sentence stem, as well as a total score. The WUSCT has shown very strong reliability of numerous types and has been quite well?validated as measure of ego development (Garb, Lilienfeld, Wood, & Nezworski, 2002). The RISB is less well researched, but reviews have shown adequate interrater, split?half, and test?retest reliability (Sherry et al., 2004).

Using the objective scoring method on the RISB, one study was able to reliably detect poor psychosocial adjustment in college students, differentiating those receiving mental health services 80% of the time (Lah, 1989). Similar results were found in detecting delinquent adolescent high school males compared to peers (Fuller, Parmelee, & Carroll, 1982). One study even found a moderate relationship between response types on the RISB and psychopathy as measured by an objective measure (Endres, 2004). The WUSCT, not being designed to measure psychopathology, has been rarely employed for such purposes in the reported literature. One study that did compared ego development (as measured by the WUSCT) in adults with and without a history of psychiatric disorders, finding that the WUSCT scores in higher functioning persons with a history of psychiatric disorders were more like the normal controls (Riberio & Hauser, 2009). One exception is a study by Westenberg and colleagues (1999), which found WUSCT scores were able to accurately distinguish children with separation anxiety from children with more generalized anxiety problems.

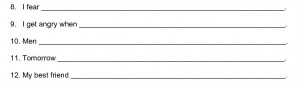

Unfortunately, as was the case with the other measures summarized previously, it appears that few clinicians use objective scoring methods when utilizing SCTs, instead relying on subjective interpretations (Weiner & Greene, 2008). There certainly is the potential to assess certain clinically relevant symptoms from a person’s answer to a sentence stem, particularly stems designed to elicit typical cognitions or behaviors seen in various disorders. For instance, stems to potentially assess social anxiety might include “WHEN I ENTER A ROOM _________” or “PEOPLE THINK I _________” while generalized anxiety symptoms might be examined using stems such as “I OFTEN THINK _________.” It is not known, however, if many or any clinicians construct and use such stems, and there are not any published SCTs that do so. Sentence completion tests, although some are useful in assessing general distress (RISB) or ego development (WUSCT), do not therefore appear to be a diagnostically useful tool in the assessment of most mental disorders as commonly employed. Development of new, specific stems may prove useful, however, and research into the issue should be encouraged.

Verdict – Likely the most useful and psychometrically sound of the projective measures, but still has vast room for improvement

———————————

Next time, I will be writing about the (non-projective but very widely used) Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. I will conclude the series with a look at scientifically reliable and valid measures of personality.

(For a full list of the works I’ve cited above, feel free to email me.)