As mentioned in my previous post, this is the second in a seven part series examining science and pseudoscience in the field of personality and psychopathology assessment. My goal is to expose the less than stellar underbelly of some of the most commonly-used and well known measures, particularly those that fall under the grouping of “projective” assessments. The first measure I will turn a careful and critical eye to is one of the most easily recognized psychological measures, the Rorschach Inkblot Method. Be warned, this is a long read.

———————————

To gain an understanding of the strength of beliefs for and against the use of our first test, the Rorschach (also called the Rorschach Inkblot Method [RIM] has been described as being “the most cherished and the most reviled of all psychological assessment tools” (Hunsley & Bailey, 1999, p. 267). Frequently listed as one of the most commonly used psychological measures by clinical and school psychologists (Archer & Newsom, 2000; Hojnoski et al., 2006) and frequently taught in the clinical psychology doctoral programs (Belter & Piotrowski, 2001), although anecdotal evidence suggests a decline across the past decade. The Rorschach also holds a grip on the public imagination, as evidenced by the use of similar inkblots in media from comic books (“Watchmen” by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons) to music videos (“Crazy” by Gnarls Barkley).

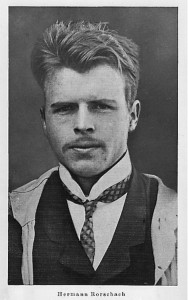

Hermann Rorschach’s development of the test that would bear his name is an interesting story. He was apparently intrigued as a youth (as was much of Germany) by a popular parlor game called Klecksographie (roughly “Blotto” in English), where one would drip ink onto a piece of paper, fold it in half, and then compete to give the most numerous or interesting answers (Exner, 2003). Psychological research using inkblots had been conducted by a number of researchers in the early part of the 20th century, but had primarily confined itself to the areas of visual perception and memory processes, although Alfred Binet researched their use in measuring intelligence (Zubin et al., 1965). Rorschach, however, was either unaware or ignored these lines of research when, in 1918, he created his blots and developed their usage. He did, however, appear to be inspired by work conducted by a medical student in Zurich, who was unable to show success in distinguishing psychotic patients from non?patients using responses to inkblots (Gurvitz, 1951).

Rorschach’s inkblots were not what one would have seen in a game of Blotto, however. He appears to have painstakingly constructed them using ink and watercolors, rather than relying purely on chance or random drips and patterns (Exner, 2002; Morganthaler, 1954). Based on his only major work (he died at age 37, only nine months after publication of it), Rorschach was particularly concerned with two factors in a person’s response to the blots: movement and color (Rorschach, 1921/1964). He does not appear to have been influenced by Freudian theories in constructing the inkblots or their interpretation, and instead had his own theory that the perception of movement and color would give insight into personality. In particular, he thought movement responses were related to introversion, while color responses were related to extraversion (“extratension” in his terminology).

The idea that perception of movement and introversion were related appears to be based in part on muscle movement and dream research by a philosopher in the 1800s named John Mourly Vold (Ellenberger, 1993). Rorschach took Mourly Vold’s idea that inhibition of movement during sleep would cause more dream imagery involving movement and applied it to the responses generated by his inkblots. In other words, his theory was that introverts should see more images that are moving in the blots, due to their being psychologically inhibited. Rorschach also outlined a theory that the perception and use of color in descriptions of the inkblots was related to affect and extraversion. In particular, those who used more color responses were more extraverted and likely to show high levels of emotion. Unlike with his ideas about movement, however, his theory about color seems to have been pulled from common vernacular (“black moods” for example) and personal opinion rather than any research or previous theories (Rapaport, Gill & Shafer, 1946). Rorschach also seemed particularly interested in the balance of introversion and extraversion, called “Experience Balance” in English (abbreviated EB). The ratio of movement (M) to color responses, he believed, would reveal a person’s “basic experience and orientation toward reality” (Wood, Nezworski, Lilienfeld, & Garb, 2003).

Rorschach’s reasons for focusing on color and movement, therefore, need to be examined to see if they are actually supported by a preponderance of scientific evidence. A review of the literature shows that the answer is, for the most part, “no.” EB, for example, has not consistently been demonstrated to be related to introversion or extraversion (see Holtzman, 1950 or Wysocki, 1956 for disconfirming evidence; Allen, Richer, & Plotnick, 1964 for confirming), and Color responses have not been consistently related to any particular diagnosis such as depression (for a review see Stevens, Edwards, Hunter & Bridgman, 1993). It should be noted, however, that some of Rorschach’s hypotheses do have some consistent support. For example, that a more intelligent person would provide higher numbers of M responses has been supported to a moderate degree (see Frank, 1979 for a review), as have some indicators of psychotic disorders (see Dawes, 1994; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2001).

So, was Rorschach right? The answer is “mostly not” with the occasional “yes.” While his major hypotheses have not been shown to be correct, some minor ones have support. What does this mean for the test as a whole, then? Should it all be thrown out? These inconsistencies and concerns led to numerous within?group conflicts during the 1930s and beyond, as different groups of researchers and clinicians developed further types of scores, or refined the meaning of certain scores (see Exner, 1969 for a review of major systems of interpretation). It was during these conflicts that some began to use the Rorschach as a more psychoanalytically?oriented test, interpreting responses to blots as if they were dreams (content approach) rather than relying on a more formal structural approach (e.g., following Rorschach’s methods).

Furthermore, well?conducted research in the 1950s showed that the Rorschach was not more useful (and was in fact slightly less useful) than a more objective measure of personality, the MMPI, and appeared to highly overpathologize normal individuals (e.g., Little & Schneidman, 1959). Further research showed that it added little to nothing in the way of incremental validity if one already had access to biographical information and a person’s history (see Garb, 1998 for a review). By the beginning of the 1960s, most research?oriented and scientifically?based psychologists thought the Rorschach was not a useful instrument (see critiques by Chronbach, 1949; Jensen, 1958).

Such criticism and lack of scientific support led directly to a number of reform attempts for the Rorschach. The most complete one, and the one that likely saved the Rorschach from being consigned to the graveyard of psychological tests, was John Exner’s Comprehensive System (CS; 1974, 1993). The CS included reviews of the literature, norms, and administration guidelines – all things that were lacking at the time. Exner also led extensive research into reliability and validity of the traditional scores, while at the same time developing new ones. Exner has been described as having “almost single?handedly rescued the Rorschach and brought it back to life” (American Psychological Association Board of Professional Affairs, 1998, p. 392). All the while, though, findings by researchers other than Exner or his associates began to appear, with results often in sharp contrast to those reported in the CS’s manual. In fact, the vast majority of the supportive studies cited in the latest CS manual (Exner, 1993) are unpublished studies conducted by Exner and his research team at Rorschach Workshops (Wood et al., 2003).

As research on the CS conducted by those without ties to Exner and the Rorschach Workshop began to accumulate in the 1980s and 1990s, numerous concerns that were identical to those raised by research in the 1950s and 1960s were raised: overpathologizing, low diagnostic accuracy outside of psychotic disorders, lack of relationship to objective measures of psychopathology and personality (for a review see Hunsley & Bailey, 2001; Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000). Even the norms of the CS were found to be seriously different from the results of other studies (e.g., Shaffer, Erdberg, & Haroian, 1999; Wood et al., 2001). Flaws within Exner’s own norms were even found, as over a third of his normative sample was found to not exist; from his own report, 221 of the 700 normative subjects were actually duplicate records (Exner, 2001). Of special note, the majority of supportive studies for the Rorschach have recently been published in the Journal of Personality Assessment, a well?respected journal that publishes large amounts of high quality research. It also happens to be the official journal of the Society for Personality Assessment, which originated as the Rorschach Institute, and is almost exclusively staffed by editors who are very strong proponents of the Rorschach’s use.

What, then, can be said about the usage of the Rorschach in clinical settings? Interestingly, both opponents (Wood, Lilienfeld, Garb, & Nezworski, 2000) and proponents (Weiner, 1999) conclude that it should not be used diagnostically. To wit, “Rorschach data are of little use in determining the particular symptoms a person is manifesting….Accordingly, the nature of these symptoms is better determined from observing or asking directly about them than by speculating about their presence ” (Weiner & Greene, 2008, p. 396). Clinically, there are some CS scores that are related to intelligence and psychotic disorders, just as Rorschach’s original system found almost 90 years ago (Wood, Nezworski, & Garb, 2003). But in terms of relationship to currently used diagnostic categories, there is currently no solid scientific evidence that using the Rorschach under the CS can accurately and consistently assist with the diagnosis of mental disorders in general (outside of psychotic disorders), or any specific category of anxiety, mood, or eating disorders, to name a few (Wood et al., 2000). There is, however, a non?CS scale – the Elizur Anxiety scale – that relates to realworld anxious behaviors (Aronow & Reznikoff, 1976; Goldfried, Stricker, & Weiner, 1971), although not to specific disorders. Unfortunately, it is best regarded as a research instrument, given the lack of standardized norms or methods of administration (Wood, Nezworksi, & Garb, 2003).

In summary, then, the Rorschach began life in 1922 as a theoretically shaky, non-empirically supported test for the majority of psychopathology (psychotic disorders being the exception). Despite almost 90 years of research and usage on it, and various iterations of scoring and administration criteria, the preponderance of evidence today indicates that it has changed little over years. There is not any reasonable, empirically?supported reason to use the Rorschach as a tool to assist in the diagnosis of any mental disorder.

Verdict – Pseudoscience for the vast majority of claimed uses

———————————

Next time, I will be writing on the Thematic Apperception Test. Then I will move onto projective drawings, sentence completion tasks, and the (non-projective but very widely used) Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. I will conclude the series with a look at scientifically reliable and valid measures of personality.

(For a full list of the works I’ve cited above, feel free to email me)