A recent r/skeptic thread entitled “How does everybody here feel on the subject of personality testing?” is the inspiration for my next few posts. One thing I encounter fairly frequently in every day life (online and off) is the perception that large amounts of what I, as a clinical psychologist, do is not really scientific. Now, once people get to know me better, they assume that maybe I’m scientific, but that enormous amounts of the field of clinical psychology as a whole aew bunk.

Unfortunately, I would say that I agree. See, I’m a huge proponent of evidence-based practice, but not everyone is a practitioner of it.

Stated simply, evidence-based psychology (EBP) is a guiding principle that means a therapist, whether that person is a psychologist, counselor, social worker, or psychiatrist, is guided in the treatment and assessment methods they use by the current best practices as defined by scientific evidence. Unfortunately, many therapists have not been trained in these methods, and instead rely on intuition, what they think has worked well, or what they were trained in – regardless of the evidence or lack thereof for it’s effectiveness.

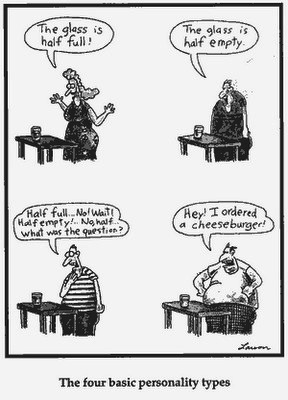

For my next few posts, I’m going to be specifically looking at the field of personality assessment, and demonstrating how some of the most commonly used and widely-known measures are a completely and utter waste of time and energy, not to mention often pseudoscientific.

———————————

The assessment of an individual’s psychological state – thoughts, feelings, behaviors – is an enormous part of a psychologist’s life. Indeed, the story of clinical psychology prior to World War II is the story of psychological assessment, from Lightner Witmer’s first psychological clinic to Army Alpha and Army Beta to the Wechsler?Bellevue intelligence test (Plante, 2011). Unfortunately, as is the case in the development of most scientific fields, not all early development was actually progressive. Many health fields in their infancy embrace non? supported (outside of anecdotal stories or personal experience) theories, treatments, or measures of assessment. In medicine, for example, we have humorism, which led to bleeding and cupping (Hart, 2001), or animal magnetism, which led to mesmerism and channeling the magnetic fluid (Baker, 1990). In clinical psychology, many today view the continued use of projective measures of personality to assess psychopathology as akin to a physician who uses trepanning to treat epilepsy – as a pseudoscientific practice which should have no place in a modern, scientific field. There are, however, numerous supporters of the use of projective techniques and tests to assess for psychopathology in both clinical practice and academia (Hogan, 2005; Hojnoski et al., 2006).

The purpose of these posts is to examine, using a scientifically skeptical but not cynical mindset, if the evidence supports the continued use of projective measures in the realm of personality and psychopathology assessment. To do so, I will first familiarize the reader with the historical and theoretical background behind the development of the most commonly used projective measures. Then, I will examine the history of the controversy of their use, beginning in the 1950s and continuing to the present day. Next, evidence specifically concerning the use of such instruments for assessment of personality and psychopathology will be summarized. Finally, conclusions and recommendations for clinical practice will be offered.

It is important to note at this point is that projective measures are often equated with psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theories of personality and psychopathology, particularly by persons unfamiliar with their history and development. However, not all measures (e.g., the Rorschach) were developed from a psychodynamic or analytic framework, although many were indeed later co?opted by clinicians and researchers from such a theoretical background. Readers should also be aware of the long?standing and ongoing controversies and debates regarding the validity and scientific status of psychodynamic theory, which has come under attacks from both within (e.g., Bornstein, 2001) and without (Fuller Torrey, 1986; Popper, 1963). There remain, however, many ardent supporters and promoters of psychodynamic theory and the usefulness of its treatment methods (e.g., Leichsenring, Rabung, & Leibing, 2004 ; Shedler, 2010).

Before turning to the specific projective measures, though, some terminology issues must be addressed. Types of measures used to assess for personality characteristics and psychopathology are often divided into two categories: objective and projective (Weiner & Greene, 2008). Objective tests make direct inferences about a person’s psychological state based on his or her self?report (or in some cases, report from significant others such as parents) to very clear questions. Projective tests, in which instructions or stimuli are more ambiguous and less structured, make indirect inferences about a person’s psychological state. The term “projective” itself comes from Frank (1939), who thought that using ambiguous stimuli would allow a person to project their “private world” onto such stimuli, and as such “interpret the material and react affectively to it” (p. 403).

This terminology can be seen, however, as heavily value?laden (e.g., “If one is objective, the other must be subjective!”) and may not be very useful. One task force of the American Psychological Association, the Psychological Assessment Work Group, even recommended replacing the label “objective” with “self?report instrument” and “projective” with “performance?based measures” (Meyer et al., 2001). Others recommended use of “self?report measures” and “free response measures” (Meyer & Kurtz, 2006). Such recommendations, however, have not been adopted by the majority of practitioners and researchers, and as such these posts will retain usage of the more familiar term “projective measures.”

———————————

Next time, I will begin a detailed examination of the most commonly used projective measures, starting with the Rorschach Inkblot Method. I will also be writing posts on the Thematic Apperception Test, projective drawings, sentence completion tasks, and the (non-projective but very widely used) Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. I will conclude the series with a look at scientifically reliable and valid measures of personality.

(For a full list of the works I’ve cited above, feel free to email me)