The Halo of Faith

Have you ever had a friend in an abusive relationship? We feel love and compassion for them, but also a mix of disgust and impatience. How could they settle for such an unworthy situation? How can they not see it the way others do?

Have you ever had a friend in an abusive relationship? We feel love and compassion for them, but also a mix of disgust and impatience. How could they settle for such an unworthy situation? How can they not see it the way others do?

The answer, of course, is that our friend is on the inside. We’re not. The view is always very different from the outside. This is one of the arguments for religious faith, that you can only understand it when you already have it. It’s a gift, like being in love, that we don’t have to explain to those who don’t have it. We can’t explain it. If they had it, they would understand. Believers want to say that we commit an error when we critique faith without having it. Let’s call this the Faith Fallacy.

But this is also what makes faith a problem in society. We live with people, so our motivations and decisions should follow rules that are communicable to others. When they aren’t, we are not really in relationship and there is no contract between people; our actions and the reasons for them appear more like the weather. Our friends need to know what drives us, but there is nothing negotiable in religious faith. It’s a unilateral position that others simply need to accept or navigate around. It’s anti-social. In relationships, our reasons have to be mutually understandable and negotiable. These are not words that describe faith.

Back to our friend. Let’s say she’s a Christian. That places her in relationship with Yahweh and Jesus. What do we know about those guys? Lest we fall victim to prejudice, let’s get all our information from our friend. When I ask Christians what they believe, the most common thing I hear is this: “Jesus died for our sins”. This statement is full of assumptions, so let’s unpack it.

First, “Jesus died for” implies that vicarious atonement is possible and desirable. Yet we never do this in our culture. When a crime is committed, we punish the perpetrator. No one can come forward and volunteer to do time for another. That wouldn’t be just or fair. To see this, all we have to do is replace the cast of characters with humans.

Let’s say you are justly accused of a crime. You await punishment, but the judge, in his mercy, tells you that he has decided to let you off the hook. But he’s not going to just forgive you. He still requires that someone be punished. In fact, he’s going to arrange the torture (let’s say with leatherworking tools) and death of his own son, an innocent man, so that you can go free.

Are you grateful? Perhaps, but we would also be repulsed at the injustice of such an arrangement. And we would be concerned about the young man. And we would question the morals of the judge. At minimum, this is a dysfunctional ruling that wouldn’t survive on appeal. At worst, the judge is off his nut and should be committed himself.

Second, we have “sins”. What sins did Jesus die for? His sacrifice was for everyone, so what sins has a 3 month old committed? Or a disabled 20 year old who has never been out of her bed or off her ventilator? The usual theological explanation is Original Sin, or the ‘curse of Adam’. Adam was disobedient, so we are all responsible and must be punished. Again, we just don’t do this in our culture. Guilt does not flow down the generations, or from one person to another. It may have in some cultures, but this idea is certainly outdated, to say the least.

Ah, but wait. We are committing the Faith Fallacy. We are looking at this arrangement from the outside. When we view it from the judge’s point of view, it’s a beautiful, compassionate sacrifice of incredible mercy. If you would only buy into it, you’d see it that way, too. And you would wear miniature leatherworking tools around your neck and kneel before giant leatherworking tools in prayer and erect enormous leatherworking tools on the pinnacles of your buildings, all in honor of this immeasurable and poignant sacrifice. Did I mention that I’m sacrificing my own son? That’s, like, the most loving thing a father can do.

How do we react to such an idea? It depends on our vantage point. From the outside, it’s clearly malignant. When we’re inside, the view is very different.

Lawyers, doctors, judges and police officers sometimes recuse themselves from working on cases because they are too close to them. We all recognize that personal or family involvement can prejudice us in ways we can’t detect or resist. In religious faith, this wisdom is reversed. Here, the prejudice and loss of perspective that come from being too close are declared to be virtues. In fact, they are requirements to get on board with certain ideas at all.

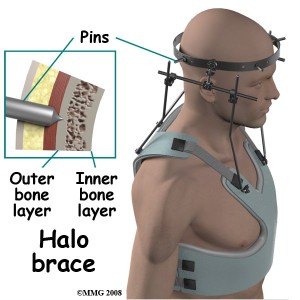

This is why I say religious faith requires a halo. Not the angelic kind, but the rigid metal ones that screw into your skull to hold your head in one position. If you shift out of that position, the appearance of your belief will change radically, often in ugly ways. So, it is vital that we keep our vision fixed in just the right way so that

Vicarious atonement appears just and fair.

Torturing and killing an innocent man seems loving.

The option of simply dropping the charges against us without a blood sacrifice is not even noticed.

The whole Christian project depends on Yahweh’s bloodlust, but it equally depends on this fact being invisible from the inside. A blood sacrifice is simply required, but the focus is on God’s mercy in punishing Jesus in our place. “You don’t know Him like I do. He doesn’t want to punish us. He’s actually a really loving guy.”

This is why stepping outside the faith and asking questions is bad form. Religious faith is a sort of hologram that disappears when you shift your perspective. It relies on a fixed vantage point that is only available when you already believe it. Faith has evolved several companion behaviors, like a posse of lampreys accompanying a shark, that deflect and discourage analysis from the outside.

One is taking offense. When someone asks a reasonable question, but one that comes from the outside, believers often take offense. This hijacks our existing cultural norm of courtesy. People are conditioned to back off when they offend someone. But asking a question from the outside of faith is not offensive, it is reasonable. But it is reasonable from the social perspective: “I want to understand you better, so I have a question about your faith.” But believers aren’t operating from a social perspective; they are inside their faith. Misapplying ‘taking offense’ is a ploy, like a squid squirting ink. They weren’t offended; they were flat-footed. You asked a question for which they had no answer.

James Carse says that ‘belief is where thinking stops’. It has to be. Belief systems are closed systems of answers. That is one of their main offerings: “Believe this way and you’ll have a complete worldview; your search is over.” Bombs of curiosity coming from over the horizon have to be deflected, and misapplying ‘taking offense’ is a survival tactic. To the frustrated believer, they shouldn’t have to deflect outside inquiries. It’s only necessary because there are still some poor souls outside their bubble. It’s a pity, but nonbelievers can never understand what they have. The only answer to questions from outsiders is “you’re not supposed to ask such questions”.

Another is willful ignorance. Now, there’s nothing wrong with ignorance; we all have it. Recognizing our ignorance is the beginning of knowledge. But willful ignorance has nothing to do with that. Its aim is to preserve a belief in the face of contrary evidence. We all do this, too, to some degree. In science, we have mechanisms like peer review, repeatability and double-blind studies to counter human weaknesses. But willful ignorance avoids those corrective measures, too. Beliefs are selfish this way. They want only to survive and they have evolved defenses for self-preservation, facts be damned. And getting along with others has to be secondary, too.

Fielding outside questions is built into science. It is actively discouraged in religious faith. Science promotes open standards, while faith sprouts walled gardens that are inherently, and by design, inaccessible to outsiders.

Which approach is most helpful on lifeboat Earth? There is one scenario where faith is socially feasible: when there is only one faith. If everyone were Muslim, for example, then the walled garden of faith would have no outsiders. If everyone were Christian, it might work, but we would still have to settle on which Christian sect to choose. And notice I said “socially feasible”; religious social systems are feasible, but autocratic.

There is no solution involving religious faith that is compatible with a free civilization. To live together, our worldviews must be accessible and understandable to others. Scientific Naturalism offers such a worldview. Religious faith spawns myriad, incompatible ones. Persisting in faith means walling ourselves off at a time when we can only survive by working together.

Most religious believers are in dysfunctional relationships with abusive gods. The gifts of faith are great, but come at an even greater price. Believers have been trained not to see things from the outside. To rejoin the wider world, they need to step outside their faith so that they can share, and answer, our concerns.

Recent Comments