Last night, I was one-half of the skeptic contingent attending a lecture given by Christian apologist Stuart McAllister at the oldest public institution of higher education in the State of Oklahoma. None of my photos turned out well, here is the closest one that I could find:

https://twitter.com/S_McAllister1/status/438852277864910848

(Same room, same lectern, different talk.)

The first half of the talk was mostly about how we cannot find deep and satisfying existential meaning in selfish material pursuits, we must reach beyond ourselves to serve others if we want to do that. Oddly enough, I’d just heard the same sentiment uttered in a completely secular context earlier that day, on a podcast called Happier with Gretchen Rubin. She was referring to a growing body of studies showing that serving other people while focusing on meeting specific concrete needs has been reliably shown to lead to greater personal satisfaction.

Doing something nice for someone else is one reliable path to greater personal happiness | http://t.co/xjnOjn8Xd1 | @StanfordBiz

— Tarak H. Rindani (@TarakRindani) January 5, 2015

Perhaps this result obtains because humans are ultra-social as mammals go, making interpersonal cooperation a long-term winning strategy in the ongoing Darwinian struggle for healthy offspring. Or perhaps it is because the Abrahamic deity (who encouraged genocide and neglected to ban slavery) intelligently designed us to be empathetic to the plight of others. Other hypotheses abound, no doubt, but those two appear to be in particular tension.

|

|

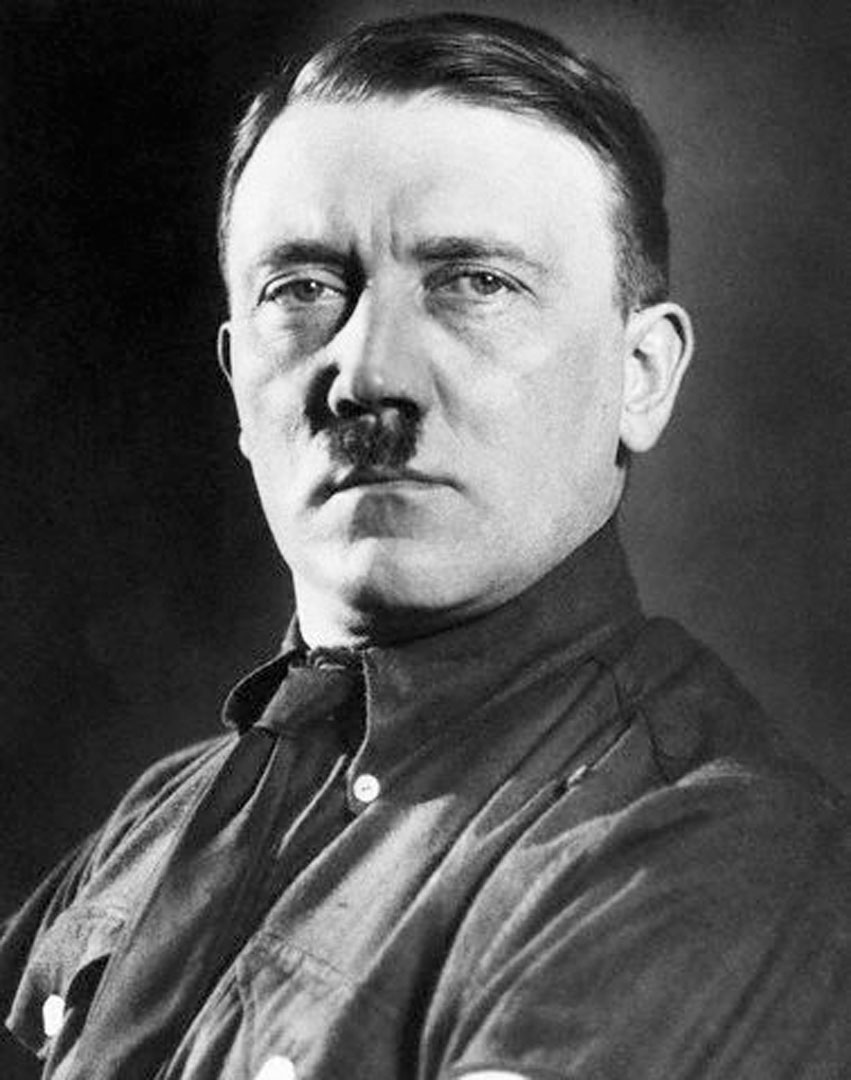

Probably the most striking slide of the evening, at least from where I was sitting, featured nothing more than a large portrait of Dietrich Bonhoeffer on one side and one of Adolf Hitler on the other. Having been conditioned to the old internet norm that whomever mentions Nazis first (typically in comparison to his opponents) automatically loses the debate, I half-consciously expected that this slide would mark a major turning point in the talk, but McAllister plowed onward. Nevertheless, it bears consideration.

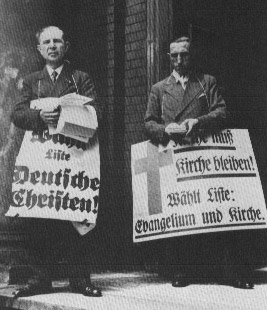

I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that a roomful of American Protestants can agree with any randomly selected roomful of Secular Humanists on the question of who lived a better life, when it comes to a head-to-head between Bonhoeffer and Hitler. It should be clear, however, that comparing the lives of these two men—however exemplary they may be of their respective worldviews—isn’t going to provide us with any particularly useful generalizations here in the 21st century. There was indeed an historic struggle between National Socialism and Bonhoeffer’s anti-Nazi Confessional Church, once upon a time, and you can probably guess who won out in that struggle of worldviews. [Hint: Check the logo.]

If we are going to have a serious discussion about the struggle of worldviews in pre-WWII Germany, by all means, let us have a serious discussion about the struggle of worldviews in pre-WWII Germany. This is not accomplished by cherry-picking the most morally exemplary person you can find to represent “orthodox” Christianity, but by recognizing the historical failure of the Confessional Church to win support from the bulk of German Protestants, not to mention the abjectly collaborationist stance of the Catholic Church regarding the rise of European fascism. The Christian worldview had no lack of adherents throughout fascist Europe, but unlike freethinkers, Christians were rarely actively suppressed rather than simply bought off and co-opted. This should tell you something about which worldviews were considered a genuine threat to the rise of the ubermenchen.