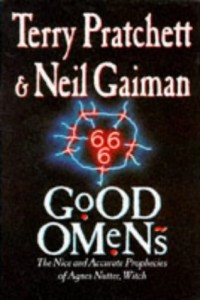

In my interview with Sara Mayhew we heard how skeptics and freethinkers can recapture the art of storytelling for the sake of encouraging people to question common assumptions about humanity and the world we live in. Today’s post highlights an excellent example of doing just that, a piece of modern fantasy writing which operates as an effective satire on an entire Biblical genre.

The official ambassadors of both Heaven and Hell live well on Earth, and they have become quite comfortable in their postings. One might even say that the angel Aziraphale and the demon Crowley have gone native, as it were, having become overly enamored of humankind. This makes it difficult for them to relish their most recent assignment: taking the necessary steps bring about the apocalypse. Meanwhile, the son of Satan isn’t exactly going according to plan either. Having been accidentally misplaced with ordinary English parents, instead of a specialized Satanic secret society, Adam Young has been subconsciously using his diabolical powers to create an idyllic British childhood for himself, rather than honing them to take over the world. Added into the mix are the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (naturally) and the only true book of prophecy in all of history: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch.

Needless to say, as a collaboration between Pratchett and Gaiman, this book is quirky, darkly humorous, and irreverent. The narrative plants seeds of freethinking and skepticism throughout, prompting the reader to think for themselves without being at all heavy-handed about it. Here follows a salient example, from right at the beginning of the book:

God moves in extremely mysterious, not to say, circuitous ways. God does not play dice with the universe; He plays an ineffable game of His own devising, which might be compared, from the perspective of any of the other players, to being involved in an obscure and complex version of poker in a pitch-dark room, with blank cards, for infinite stakes, with a Dealer who won’t tell you the rules, and who smiles all the time.

It is difficult to read this without recalling all the various attempts at divine proof, disproof, rebuttals, counterebuttals, and so forth. The books prompts you to think about the ultimate nature of reality, morality, and other such profound stuff, but like Adam Young, you are having too much fun to consciously notice just how much hangs in the balance.